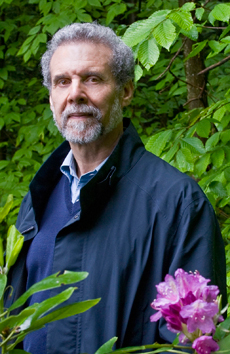

I recently was blessed with the opportunity to talk with author, psychologist, and science journalist Daniel Goleman about his new book, The Brain and Emotional Intelligence: New Insights. Among Goleman’s prolific body of work is the best-selling book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ, a subject that he has revisited and expanded upon in his newest offering.

Tricycle: How does understanding the brain help us manage stress?

Daniel Goleman: There are several ways that understanding some brain mechanics and having basic neural tools at hand can help us manage stress. First of all, we have to realize that there’s no escaping stress completely; this is the nature of life. Some of what’s called samsara is what other people call “stress”. When we’re stressed the part of the brain that takes over, the part that reacts the most, is the circuitry that was originally designed to manage threats—especially circuits that center on the amygdala, which is in the emotional centers of the brain.

The amygdala is the trigger point for the fight, flight, or freeze response. When these circuits perceive a threat, they flood the body with stress hormones that do several things to prepare us for an emergency. Blood shunts away from the organs to the limbs; that’s the fight or flee. But the response is also cognitive—and, in modern life this is what matters most, it makes some shifts in how the mind functions. Attention tends to fixate on the thing that is bothering us, that’s stressing us, that we’re worried about, that’s upsetting, frustrating, or angering us. That means that we don’t have as much attentional capacity left for whatever it is we’re supposed to be doing or want to be doing. In addition, our memory reshuffles its hierarchy so that what’s most relevant to the perceived threat is what comes to mind most easily—and what’s deemed irrelevant is harder to bring to mind. That, again, makes it more difficult to get things done than we might want. Plus, we tend to fall back on over-learned responses, which are responses learned early in life—which can lead us to do or say things that we regret later. It is important to understand that the impulses that come to us when we’re under stress—particularly if we get hijacked by it—are likely to lead us astray.

It’s extremely important to widen the gap between impulse and action; and that’s exactly what mindfulness does. This is one of the big advantages of mindfulness practice: it gives us a moment or two, hopefully, where we can change our relationship to our experience, not be caught in it and swept away by impulse, but rather to see that there’s an opportunity here to make a different, better choice. I think that understanding the basic neural mechanisms involved is an aid to mindfulness because it tells us we don’t have to get swept away.

Tricycle: Fascinating. It seems that it is through awareness that we have any choice at all, as opposed to just letting our reactions dictate everything we do.

Daniel Goleman: Yes, exactly, the unconscious mind is completely happy to make all of our decisions for us, and to run us on “automatic,” through habitual sequences that roll on outside of our awareness—and so without our seeing that a choice was even there to be made. When we are mindless, so to speak, we’re piloted through our day seemingly by whim, by pure habit. Mindfulness lets us step out of that rut and see that there’s another road we could take and actually take that road. So it’s a very powerful choice point in the mind.

Tricycle: We have quite a capacity for autopilot, it seems.

Daniel Goleman: Yes, exactly.

Tricycle: So stress reactions and various difficulties are hardwired into the brain, so to speak. I’m curious—are ethics or morality hardwired into our brains as well?

Daniel Goleman: There’s some evolutionary thinking that there tend to be four or five universal dimensions of ethics and ethical choice, but no one is saying there’s some specific spot in the brain which is our ethical center. It’s certainly more diffuse than that. The psychologist Jonathan Haidt proposes an evolutionary theory that there are five or so universal dimensions of ethics. He has written about how universal, for example, a sense of fairness seems to be, or the positive value of cleanliness and negativity of dirtiness, or a concern with larger meanings. So, it may be that our brain is designed to foster our thinking about such ethical concerns. I don’t know if you could say it’s hardwired but I think the capacity for ethical concerns seems to be a universal brain function.

Tricycle: How do you feel about all the time that we’re spending online these days? How might this effect our brains?

Daniel Goleman: I think it’s an enormous experiment with our sense of community and our children. Evolution designed the human brain for face-to-face human contact, particularly our capacity for empathy, which, of course, is very strongly related to our sense of ethics. Empathy is the essential factor for compassion but online we may be disabling this. The social centers of the brain seem to act like an interpersonal radar attuning to the person we’re with, and activating in our own brain what’s going on with that person—their feelings, their intentions, their movements. Because we have this inner sense of what they’re doing we don’t have to think about it; this is another automatic function.

Daniel Goleman: I think it’s an enormous experiment with our sense of community and our children. Evolution designed the human brain for face-to-face human contact, particularly our capacity for empathy, which, of course, is very strongly related to our sense of ethics. Empathy is the essential factor for compassion but online we may be disabling this. The social centers of the brain seem to act like an interpersonal radar attuning to the person we’re with, and activating in our own brain what’s going on with that person—their feelings, their intentions, their movements. Because we have this inner sense of what they’re doing we don’t have to think about it; this is another automatic function.

Tricycle: Like mirror neurons?

Daniel Goleman: Mirror neurons are one of the main classes of neurons that have been discovered in the social brain—all of these social circuits together keep things operating smoothly during interactions. But when we’re online there’s no channel for our social brain to get feedback. The mirror neurons have nothing to read, and so we’re operating in the dark. This may create, for example, a negativity bias to email, where the sender thinks the message is more positive than does the person who receives. This also means people are more likely to experience what’s called “cyber-disinhibition” which means that, say, you’re having a little bit of an emotional hijack and if you were face-to-face your social circuitry might tell you “Well, it would be better to say this than that.” In other words, you might be artful about it. But online it has zero feedback; that’s the disinhibition which gives rise to what’s called flaming. Flaming is when somebody’s really agitated and they sit down and pound out a message all in caps, and they hit “send” and then immediately regret it; it’s a classic online hijack. So, on the downside, there also may be some emotional numbing, some deadening of empathy, and all of that means that we may be fraying social connections as more and more interactions become virtual as on Facebook and less and less face-to-face. Then there is the big experiment that is perhaps the most troubling: kids are spending more and more time during childhood online. This changes the way we have always taught social and emotional skills in life, in day-to-day interactions. If kids are spending fewer hours of time together in person and more and more hours online we might be de-skilling entire generations in essentials for a full human life.

Tricycle: Do you recommend any practices or activities that might help people living in this age develop their capacity for emotional intelligence?

Daniel Goleman: The good news is that there are ways to cultivate emotional intelligence. But first remember that emotional intelligence is a set of human skills; it is not one monolithic ability. It includes self-awareness, it includes managing your emotions (or “self-regulation) which doesn’t mean suppressing emotions, but not letting your disturbing emotions get in the way of life and also marshalling your positive emotions and passions for a full life. Third is empathy, sensing how other people are feeling and a general social awareness, and fourth, putting that all together in social skill during interactions.

I would say that there are many aspects of dharma practice that would facilitate different parts of emotional intelligence. Tonglen practice, for example, is explicitly attuning into the other person and I think that must strengthen empathy. I have yet to see the research study that shows that but I would bet that that’s what it would find. I also think that the ethical dimension of dharma practice is implemented by strengthening our self-regulation, and I think that meditation practice generally is a way to enhance self-awareness. So I can see many, many ways in which dharma practice itself could give a boost to different aspects of emotional intelligence.

Tricycle: Can you talk about the relationship between motivation and emotion?

Daniel Goleman: Motivations are drivers of positive emotion. When we do the things we are motivated to do, and some people are motivated to have strong connections with other people, those things will give us a kind of spontaneous high. Some people are motivated to strive incessantly for achievement, while some people are motivated to exert power by influencing other people, some for the better, some for the worse. So, I think that the relationship is that one is the driver of the other. Our motives determine what we enjoy. Our values, on the other hand, are a little different from our motivations. Our values are our sense of what we should do and what we should like and it’s clearly best to be in a situation where our values are aligned with our motives. Many people are stuck in jobs they hate and it’s because of values say “well, you should be doing this” and their motives are somewhere else. Howard Gardner, who is at Harvard, has done research on what he calls “Good Work” which is work where people are fortunate enough to align their values, that is their sense of ethics, with their emotions, what engages them, and also what they’re good at, their excellence. So when you align excellence and ethics and engagement, then you have a calling that you utterly love. It may or may not be a paid job, but it gives your life the most meaning and is most satisfying to you.

Tricycle: Is that like self-actualization?

Daniel Goleman: I would say that’s an ingredient in self-actualization and that self-actualized people find their way to that kind of work or calling.

Tricycle: What in your research is exciting and interesting you at the moment? What are you hoping people get from your new book? In short, give me a snapshot of Daniel Goleman right now.

Daniel Goleman: Well, the reason I did this digital book, The Brain and Emotional Intelligence, is that I don’t stop pursuing an area once I finished a book about it. I wrote Emotional Intelligence, Social Intelligence, and Working with Emotional Intelligence but I’ve continued to be interested in what science can reveal to us about our lives and particularly what the newly emerging brain science can reveal to us. My profession is as a science journalist; I was at The New York Times for a dozen years before Emotional Intelligence became a career in itself and I continue to try to harvest scientific findings that are kind of news we can use that have real applications to life. This is extremely satisfying to me to continue to share this with others who are interested by publishing a shorter book digitally and to do it quickly instead of setting aside three years of my life to do a conventional book. So, I’m very happy about this.

♦

To purchase The Brain and Emotional Intelligence: New Insights click here!