This guest blogpost comes our way from Dennis Hunter, a writer currently coordinating the upcoming Yarne retreat with Pema Chödrön at Gampo Abbey in Nova Scotia.

These days, a lot of us are asking the question: What is Western Buddhism? Often, the inquiry seems to focus on the “Western” part. What is uniquely Western about the Buddhism we are practicing? How does it differ from traditional Asian Buddhism? How is Western culture changing Buddhism, and vice versa?

But what do we mean by “Buddhism,” anyway? We often use that word as if Buddhism were one unitary thing, when really (like everything else, and like the Buddha taught) the juggernaut of Buddhism is made up of component parts, and each of those parts is made of component parts, and so on. When we talk about Buddhism in the West, what do we mean? Zen? Theravada? Tibetan Buddhism? Nichiren? Pure Land? Shingon? Some conglomeration of all of these? Something else?

If we could put “Buddhism” under a microscope and look with great magnification at its many traditions and schools and lineages and teachers and practitioners, we might find it is webbed with arteries and capillaries, riddled with neurons and mitochondria—much the same as we are. Mysteriously, the ongoing process of becoming and unbecoming that we label as “Buddhism” happens in the general vicinity of these component parts, and seems to adhere to them—but nowhere can we pinpoint its exact location. There is no one thing that can be called “Buddhism,” just as there is no single place or culture that encompasses the entire “West.”

What we call Buddhism is a widely distributed network phenomenon designed to optimize the human experience. Like the Internet, it started out as someone’s idea, but then spun out of control: no one person or group now owns it, and it is being modified and updated from day to day in millions of little increments, from every corner of the known world.

Where is “the Internet?” It seems to adhere somehow to the computers and networks that are part of it, but the Internet itself can’t be found. Where is “Buddhism?” It seems to adhere to the people and networks that are practicing it, but the Buddhism itself can’t be found. Yet both the Internet and Buddhism can be demonstrated, utilized, applied in countless ways.

If there is anything unique about “Western” Buddhism at this moment, perhaps it is that all of the world’s Buddhist traditions—as culturally and doctrinally distinct from one another as a Southern Baptist is from a Russian Orthodox—have descended upon us at once. We are living now in a flux of pan-Buddhist dialogue taking place in a Western crucible, blending traditions that for two-and-a-half millennia have evolved in separate geographic and cultural regions. Buddhism’s embrace of Internet technologies in the last two decades has speeded up this process enormously.

Earlier this year, I heard from a hardcore Vipassana practitioner living in Scotland, who had just finished sitting a Zen sesshin and was preparing to attend a Mahamudra retreat the following weekend. Bam! Just like that, intensive practice in three completely distinct Buddhist traditions, with wildly different approaches, in the space of one week. Was there a previous time and place in history when such a broad range of Buddhist traditions was so freely available to one person, and so ripe for the picking?

This smorgasbord of Buddhist traditions also creates confusion—especially for the beginning student who is not firmly grounded in one tradition from the start. Beyond the obvious danger of bringing a consumer’s “shopping mentality” to spiritual practice—going from one tradition and teacher to another and always leaving them behind when they begin to provoke discomfort by challenging your ego—there is also the risk of mixing views from different traditions in an unskillful way.

Still, despite the potential confusion, to be a carrot bobbing in this Western melting pot of Buddhist traditions is to be part of a new fusion cuisine that is being consumed even as it is being cooked. If you listen to a few episodes of Buddhist Geeks podcasts, or read an entire issue of Tricycle or Buddhadharma from cover to cover, the flavor of your understanding will be at least subtly colored by teachings from other Buddhist traditions. It is unavoidable.

In my own practice, I have benefited from this kind of fusion. Although I study with a Tibetan teacher and look towards the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism as the primary lighthouse by which I navigate the waters, I have at times experienced bubbles of conceptual confusion and intellectualization that were helpfully popped by the sharp concision and no-nonsense directness of Zen teachings. At other times, exposure to the Theravadan view of the stages on the path of awakening—different in many ways from the Mahayana and Vajrayana views—has helped me view the teachings and practices in a more expansive light. I have even deepened my Buddhist path, at times, by incorporating spiritual teachings and practices from outside of Buddhism altogether. As long as I feel firmly rooted in my “native” tradition, I find this sort of cross-fertilization to be fruitful.

I now have to admit, though, that I know less than I once imagined I did what “Western Buddhism” is, or what it may become. It feels sometimes that there are as many “Western Buddhisms” taking shape among us as there are Western Buddhists who practice them. As with the emergence of Linux in the world of computers, perhaps what we are witnessing in the West today, with so much polymorphous blending of traditions, is the emergence of Open-Source Buddhism. (This moniker is, in fact, already in use on numerous websites.) Like the populist software movement from which it borrows its name, Open-Source Buddhism proposes a grassroots, do-it-yourself alternative to the old closed, proprietary operating systems. And it may yet produce new applications that were not possible within the framework of those systems.

However, buyers beware: I have dabbled in Linux, and frankly it gives me a headache. I am, in fact, writing this on a Linux-driven machine that someone bamboozled me into buying a couple of years ago, using a simplified, Linux-for-Mom-and-Pop user interface called Ubuntu that attempts to bring open-source computing to the masses. While I adore the cultural philosophy of openness and integrity and interdependence that stands behind my computer’s operating system, on a pragmatic level it often leaves much to be desired. Performing even basic actions—installing a new software program, for example—seems to demand an almost hacker-like degree of technical proficiency. There is no central help desk to turn to when something goes wrong—and something is always going wrong. Time and again, I have searched for answers to things that ought to have been simple, and in response I have been thrown into jumbled web forums where self-appointed Linux gurus “explain” the solution to my problem in a language that might as well be Martian for as much good as it does me. For two years I have been stumbling, wide-eyed, through what I regard as the Wild West of operating systems.

Open-Source Buddhism, I suspect, is much the same. Already emerging in our midst, it is full of great promise and potential—but actually using it, at this point, is not for the faint-of-heart. Its day may be coming soon, but it has not arrived just yet.

Meanwhile, in aligning yourself with any established tradition, you will trade off some of your freedom and idealism, and you will make yourself vulnerable to certain flaws that are inherent to those systems—but in return you may have a better user experience. You will have access to hands-on training, the support of peers, and expert technical support that are difficult to find in the open-source world. In the realm of computer programming, I do know people who are highly proficient at using Linux, but it must be said that they are people who first knew their way around at least one of the old, proprietary systems very, very well. They didn’t start out as open-source gurus.

The lesson? Pick the tradition that resonates most with your heart and mind, and immerse yourself in it as completely as you can. Rely on a qualified expert to help you fine-tune your machine. Work out the bugs, and eliminate the malware. Know how to use your chosen operating system thoroughly and properly. Learn how to trouble-shoot when problems arise. Then, and only then, will migrating to Open-Source Buddhism become a truly viable option.

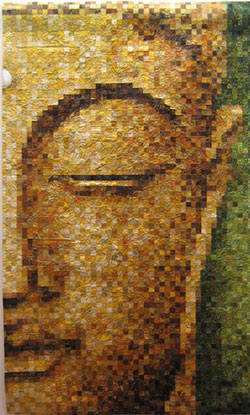

Image 2: “Buddha quilt,” from the Flickr photostream of artethgray.