The Art of Happiness

A Handbook for Living

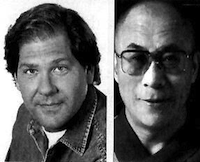

His Holiness the Dalai Lama & Howard C. Cutler, M.D.

Riverhead Books: New York, 1998

336 pp.; $22.95 (cloth)

Halfway through his new book, The Art of Happiness, the Dalai Lama interjects a personal story: There was once an older monk living as a hermit, more accomplished in meditation than the Dalai Lama himself. The hermit used to come to visit His Holiness to receive teachings as a sort of formality. On one such visit, the monk asked the Dalai Lama about doing a specific high-level, esoteric practice. The Dalai Lama remarked, rather casually, that this demanding practice was meant for someone younger, that it was best begun in one’s mid-teens. Shortly thereafter, this monk committed suicide in order to be reborn in a younger body.

“How did you deal with your feeling of regret?” asks psychiatrist and co-writer Dr. Howard Cutler. “How did you eventually get rid of it?”

“I didn’t get rid of it,” the Dalai Lama responds. “It’s still there.” Though not a heavy feeling that pulls him down, the regret is still with him.

It is in moments such as this one that The Art of Happiness surpasses itself. In giving us a glimpse at how the Dalai Lama deals with his own mind, it momentarily frees us from our naïve attachments to notions of psychological or spiritual well-being. The Dalai Lama does not even try to get rid of his regret, and, we learn, he is also not indulging in it. His radical self-acceptance jumps off the page at us.

It is in moments such as this one that The Art of Happiness surpasses itself. In giving us a glimpse at how the Dalai Lama deals with his own mind, it momentarily frees us from our naïve attachments to notions of psychological or spiritual well-being. The Dalai Lama does not even try to get rid of his regret, and, we learn, he is also not indulging in it. His radical self-acceptance jumps off the page at us.

As the book opens, Dr. Cutler, a well-intentioned Arizona psychiatrist whose work this book really is, comes clean: He wanted to write a conventional self-help book in which the Dalai Lama would give clear and simple answers to life’s most difficult questions. He wanted to present a series of case studies to His Holiness, based on his own work with patients, and then codify the Dalai Lama’s responses into a set of general principles. Remnants of this original intention are still apparent in the book’s subtitle, “A Handbook for Living.” Dr. Cutler began his study by telling the Dalai Lama about a woman who persisted in self-destructive behavior despite its evident negative impact on her life. He then asked His Holiness for an explanation and suggestions on how to advise treating her.

“I don’t know,” the Dalai Lama replied, as he shrugged his shoulders and laughed, waiting for the next question. Dr. Cutler had to quickly rethink his strategy for the book.

What resulted from their dialogue is something a little more free-form, stitched together out of transcripts of public talks and private interviews. At times, the seams show, but the cumulative impact gradually sneaks up on you, much like the Dalai Lama himself. Dr. Cutler never quite shakes free from his initial attachment to the self-help book model. He insists on supporting the Dalai Lama’s words with the latest psychological study of the debilitating effects of anger on our arteries, from the University of Maryland, and succeeds only in undercutting the power of his message. At one point, though, he lets down his professional guard and confesses to His Holiness that he, too, suffers self-doubt in his work “I don’t know …. Sometimes with my patients for instance…some are very difficult to treat…Sometimes I just don’t know what to do with these people, how to help them… It makes me feel incompetent, and that really creates a certain kind of fear, of anxiety.”

The Dalai Lama is very sympathetic. “Are you able to help 70 percent of your patients?” he asks. When told that Dr. Cutler is, the Dalai Lama is relieved. “No problem, then,” he goes on. “If you were able to help only 30 percent, then I might suggest you consider another profession. But I think you are doing fine.”

If we can apply the same percentage to this book, then on the whole it too is doing fine. The sections on anger, self-loathing, and low self-esteem are particularly good. The Dalai Lama is at first completely unfamiliar with the idea of someone who hates himself; it is outside his experience and that of anyone with whom he has ever worked closely. But by the end of his contact with Dr. Cutler, he is working on the problem: Such people should not dwell so much on the unsatisfactory nature of the world, he counsels.

The Art of Happiness is tantalizing, not so much as a self-help handbook for living, but as a window into the Dalai Lama’s own process of being human. The more that both he and Dr. Cutler reveal, the more we learn.