Some of the Dharma

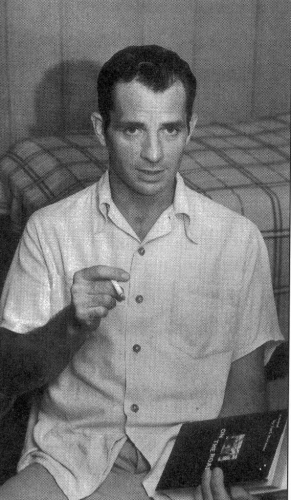

Jack Kerouac

Viking: New York, 1997

420 pp., $32.95 (cloth)

The publication of Jack Kerouac’s Some of the Dharma is a kind of event for American Buddhism. Written between 1953 and 1956, Some of the Dharma is a reading, thinking, and writing journal dedicated in large measure to the expression of Kerouac’s understanding and misunderstanding of and excitement about Buddhism. As Viking editor David Stanford writes in his introduction: “. . . he enthusiastically began Some of the Dharma as a set of reading notes, but as the months passed, it evolved into a vast and complex all-encompassing work of nonfiction into which he poured his life, chronicling his thinking, incorporating reading notes, prayers, poems, blues poems, haiku, meditations, letters, conversations, journal entries, stories, and more.” References to Buddhist texts and writers abound, but Kerouac also lets us know what he thinks of James Joyce, Boethius, St. Ignatius, Dante, and Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite. Although parts of the notebooks were shared from time to time with Beat comrades—the journal was intended always for Allen Ginsberg—the completed manuscript was rejected repeatedly by publishers despite Kerouac’s literary successes.

That Some of the Dharma should be published now, forty years after of his first great success,On the Road, must be due ultimately to two causes: the recent resurgence of interest in the Beat literary movement and the emerging popularity of Buddhism in America. Kerouac was central to the birth of both: he was the founding father of the Beat Generation and in some Buddhist circles, has been canonized as a patron saint, something like the first patriarch of Buddhism in America. Anyone who wishes to understand the Beat view of Buddhism, and the influence of that vision on Buddhism in America, needs to read Some of the Dharma.

In 1958 Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums was published, making Buddhism available to a new American clientele. Before then, D.T. Suzuki and other Zen advocates had quietly begun to transmit the ideas of Buddhism to audiences in Manhattan and Cambridge, but The Dharma Bums gave Buddhism an entirely different voice and public image. The book continues to attract new generations of readers who embrace the values expressed in Kerouac’s novels: freedom (from suburbia, mortgages, and nine-to-five family values); youth, creative thinking and writing; expansive, energetic and sometimes Dionysian living; and friendships that were both hopeful and painful. Written in 1957, The Dharma Bums emerged from the same two-and-a-half years of living, writing, and thinking that are recorded in Some of the Dharma. ButSome of the Dharma reveals much more about Kerouac’s personal encounter with Buddhism than any of his novels, and in many ways provides insight into Kerouac’s complex personality—sad in many ways, almost tragic, his life stands in stark contrast to the ideal that appeals to his readers even today. His early novels idealized a carefree, nomadic, and bohemian existence: San Francisco in the fifties, ho-boing on trains, marathon talking and drinking bouts, living in forest look-outs in the North Cascades. In a word, the works of Kerouac are primarily romantic. However, Some of the Dharma is only superficially romantic: the tension of Kerouac’s life is palpable, and Buddhism is central to the tension.

What, then, is the dharma of Some of the Dharma? Kerouac was obviously struck by the first of the Four Noble Truths: All Life is Sorrowful. His interpretation was decidedly “Hinayana” (as he called it), and never strayed far from his initial understanding. Perhaps because of his Catholic up-bringing, the sorrow that he identified was often moralistic, concerned mostly with alcohol and women. The solution was “nirvana,” but this too had a rather dualistic moralism: the rejection of his samsaric life of drinking, partying, struggling with editors, and getting entangled with women. When he began to read Mahayana texts he embraced “non-dualism,” but his rage against dualistic views was itself dualistic. At heart, Kerouac was intensely dualistic: forever pitting the spirit against the body. Perhaps this too was Catholic in nature, but Kerouac’s Some of the Dharma is anti-body, anti-sex, and anti-woman. Of course, deep down, he probably wasn’t against any of those things, but he was confused. “PRETTY GIRLS MAKE GRAVES. Fuck you all,” he wrote. And “ON SEX: If you succeed in avoiding being eaten by the crocodiles which are the womenfolk, yet forgive them and see that they are empty, you succeed in everything.”

Kerouac was confused and tortured and he used Buddhism (as he understood it) to justify his flight from the world, from pain, from his family, and from Catholicism. In a note titled “WHY DO I WANT TO LEAVE SOCIETY?” he lists several events that left him wounded, from being punched and called names as a child playing sandlot football to discovering that he was an unwanted house guest. Kerouac was torn painfully between his need for companionship and his wish for solitude. In fact, Kerouac seems to have longed for some deeper embrace while at the same time fleeing from it: in the end, he embraced the life of flight.

In Some of the Dharma the language of practice is everywhere (meditation, samadhi, dhyana, zazen), but it is mostly just talk about practice. Kerouac found his most lasting companionship in the community of Beat artists and writers. Beat Buddhism began as an intellectual adventure. Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Snyder encountered Buddhism in colleges and libraries, debating amongst their friends, but practicing very little. Their “practice” (when it existed) was self-prescribed and self-determined. Rick Fields reports in How the Swans Came to the Lake:

Except for Snyder, who sat regularly on his rolled-up sleeping bag for half an hour or so every morning, and Whalen who sat occasionally, the Buddhism [of the early Beats] was mostly literary. Kerouac’s sitting remained idiosyncratic. “He was incapable of sitting for more than a few minutes at a time,” remembers Whalen. “His knees were ruined by playing football. . . They wouldn’t bend without great pain, I guess. He never learned to sit in that proper sort of meditation position. Even if he had been able to, his head wouldn’t have stopped long enough for him to endure it. He was too nervous. But he thought it was a good idea.”

In Snyder, Ginsberg, and Whalen the enthusiasm ultimately gave way to practice—but Kerouac continued to struggle with the idea that “Buddhism” without sitting might be problematic. In the introduction to Some of the Dharma, Stanford cites a letter dated January 18, 1956, in which Kerouac askes Whalen: “Did you see where Alan Watts (in an ‘impertinent interview’ in the Realist magazine) said I had Zen flesh but no Zen bones. It made me shudder. ‘No Zen bones yet,’ he said. It must mean that when I have a belly ache I moan. I cant stand pain, I admit it. I’d like to found a kind of monastery in the plateau country outside Mexico city, if I had money . . .”

One of the most startling aspects of Some of the Dharma is the revelation that after only a few months of reading, Kerouac appears to have convinced himself that he was some kind of teacher (or at least wanted others to view him as empowered). In 1954 he referred to himself as a “junior arhat”—not yet free from intoxicants—explaining why it is dangerous for him to be a teacher and adding that he is “too young and bashful at present to take on the role of Master.” At the same time his friends encouraged him: Ginsberg proclaimed him the “new Buddha of America prose” and Snyder encouraged him to write a sutra, which he did—The Scripture of the Golden Eternity. Of course, his contact with Buddhism was primarily bookish and when he did encounter someone like D.T. Suzuki, he had an odd reaction: “I dug Suzuki in NY public library, and I guarantee you I can do everything he does and better, in intrinsic Dharma teaching by words.” Not bad for having read Buddhist texts for a year.

The internal logic of his experience supported his “teacher” fantasy. On Christmas, 1954, for example, Kerouac recorded that he had “attained at last to a measure of enlightenment.” By himself, without the benefit and company of others who had gone far ahead on the path, it is completely understandable how he might have considered his experiences extraordinary, thinking that he needed to teach others. But it is also true that Kerouac suffered his aloneness and realized on some level the need for others on the path (even if he could not move toward that need). A notebook entry dated August 24, 1954 suggests a man of despair and depression:

. . . the lowest point in my Buddhist Faith since I began last December—Reason: *Loneliness of Westerner practicing Eightfold Path alone, without occasional company of Buddhist monks and laymen. You’ve got to talk—even Buddha talked all day. Here I am in America sitting alone with legs crossed as world rages to burn itself up—What to do? Buddhism has killed all my feelings, I have no feelings . . . listless, bored, world-weary at thirty-two, no longer interested in love, tired, unutterably sad as the Chinese autumn-man. It’s the silence of unspoken despair, the sound of drying, that gets me down. . . .

His lack of “spiritual maturity” is painfully displayed, so innocent and naive that many people will recognize themselves in his blind enthusiasm, desperate to make something happen. Sometime around the beginning of October, 1954, he made a monkish resolution to eat only one meal a day, not to drink, and not to maintain friendships. It was not, he insisted, “such a bleak final” decision. He further resolved: “. . . if I break any of these elementary rules of Buddhism, which have been my biggest obstacles, hindrances to the attainment of contemplative happiness and joy of will, I will give up Buddhism forever.” By October 12 he was wavering, and changed his vow to drinking only once a week, and had a beer. On October 13 he got drunk.

Kerouac’s enthusiasm for Buddhism had some disturbing elements, but perhaps the most disturbing characteristic is the violent and seemingly blind rush toward the extreme, the unabashed embrace of the convert’s mind. In a letter to Ginsberg in March, 1955 Kerouac wrote: “Some of the Dharma is now over 200 pages & taking shape as a great valuable book in itself. I haven’t even started writing . . . I intend to be the greatest writer in the world and then in the name of Buddha I shall convert thousands, maybe millions. . . . I love everybody and intend to go on doing so . . . I have been having wild samadhis in the ink black woods of midnight, on a bed of grass.”

Ultimately it would seem that Kerouac failed in love, and that much of his negativity about sex, women and love was a deep displacement—an attempt to assuage the pain of his failure by seeing life in very narrow Buddhist terms. His Buddhism really was an attempt to deal with his own sorrow and suffering. Indeed, Kerouac reported to an interviewer in 1959 that he discovered Buddhism in a library when, after having ended a love affair and having just finished The Subterraneans after three “benzedrine-powered” days and nights, he was looking for solace: “I didn’t know what to do. I went home and just sat in my room, hurting. I was suffering, you know, from the grief of losing a love, even though I really wanted to lose it.” (Fields, How the Swans Came to the Lake) But Buddhism did not work for him. As early as 1959 Kerouac wrote to Philip Whalen: “Myself, the dharma is slipping away from my consciousness and I cant think of anything to say about it anymore. I still read the diamond sutra, but as in a dream now. Dont know what to do. Cant see the purpose of human or terrestrial or any kinda life without heaven to reward the poor suffering fucks. The Buddhist notion that Ignorance caused the world leaves me cold now, because I feel the presence of angels.”

Kerouac remains relevant to this day. He has inspired generations of young seekers. The spirit of his novels reveals a sense of freedom and energy that very much appeals to Americans—a life of outsiders looking for meaning or at least something more meaningful. Kerouac and the Beats were artists who were sensitive to the suffering of their generation and of generations to come: a life lived in the absence of personal and social values, a great HOWL of pain, and a tremendously energetic wish to believe in something—a cosmic pain-killer. Maybe Buddhism. Maybe Love.

When we balance Kerouac’s life with his novels, he becomes a mature mystery—his life and work is a kind of metaphor for Buddhism in America. He had a profound impact on shaping America’s view of Buddhism; by reading the Beats and their lives we can begin to understand the seeds of American Buddhism and to understand the difficulties that it now faces as it becomes increasingly popular.

Some of the Dharma couldn’t have been published at a more appropriate moment in the short history of Buddhism in America. The “success” of the religion here is remarkable. But how does one measure success? A recent article in the New York Times (“READ NOT THE TIMES, READ THE ETERNITIES,” Kerouac wrote) began with: “Buddhism is everywhere. Oprah Winfrey has recently been seen discussing meditation with Richard Gere,” and went on to mention more movie stars, new movies with Buddhist themes and Time magazine’s cover article on “America’s Fascination with Buddhism.” Buddhism is popular—a success. Especially because of Kerouac’s success, it seems important to turn a cool eye toward his Buddhism and separate Buddhist flesh from Buddhist bones. Kerouac desperately wanted success, and he got it. But at what price? What is lost in success? When does success cover up our failures, the very failures that need to be seen and felt if a deeper understanding is to appear?

There are lessons to be learned from Kerouac’s Some of the Dharma. The book might provide a new koan for Buddhism in America: SUCCESS AND FAILURE ARE BOTH HUMILIATING.