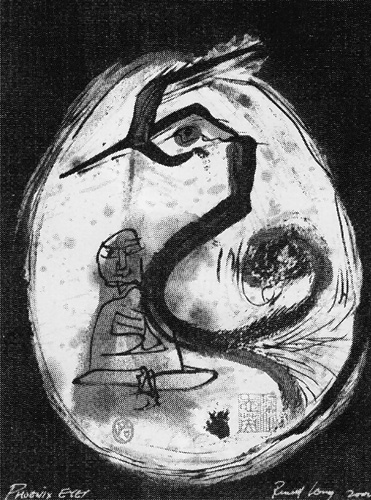

PHOENIX EYES AND OTHER STORIES

Russell Charles Leong

University of Washington Press; Washington, 2000

208 pp.; $16.95 (paper)

When young, places were important: Chinatown, San Francisco, New York, Hong Kong, Taipei where I studied for a few years in the 70s; China, where I visited in the 80s and 90s. As an older man, the physical spaces become less important and the “inner spaces” of thought, meditation, memory, poetry, and reflection begin to reveal themselves, to open up.

—Russell Leong

In a new short story collection from the University of Washington’s Scott and Laurie Oki Endowed Fund for Asian American Works, Russell Charles Leong brings together fourteen stories written over the past thirty years. In that time, Leong has created as well as written about independent Asian American cinema. He’s published numerous poems and short stories, edited anthologies of fiction and critical essays, and still made time to engage in community activism around issues such as Asians and AIDS, political youth movements, and interracial/cross-ethnic alliances. Leong currently edits Asian American studies’ primary interdisciplinary outlet for scholarship, the Amerasia Journal, based at the University of California, Los Angeles’ Asian American Studies Center.

Throughout, Leong’s understated spirituality has sustained and informed his worldly pursuits. Kinship and connection exist, for Leong, in extrafamilial bonds and political alliances rippling outward from the re-conceptualization of community begun by Asian American gays, lesbians and bisexuals; Leong’s self-awareness about the importance of community distinguishes his fiction from other attempts to merge an uninterrogated American individualism with Buddhism. It’s this perspective of Asian American Buddhism, one particular to the Los Angeles writer in its moorings but replete with universal transcendent significance, that forms the backbone of his short story collection and powerfully comments upon other syncretic American Buddhisms.

Rooted in the polyglot, infinitely variegated American Pacific and Asian communities of Los Angeles, where Asian ethnicities undergo by-the-minute redefinition among Latinos, whites, and blacks in Southern California, Leong’s fiction could be weighted down with a didactic impulse to show breadth – diverse permutations of sexual identity and ethnicity, for example – at the expense of depth.

Fortunately, his keen sensibilities as a poet and writer save him from this potential difficulty.

Take, for instance, the fine-grained detail of Leong’s opening story, “Bodhi Leaves,” in which a Vietnamese monk improvises a sangha, a Buddhist religious community, out of a suburban Orange County tract home. He asks three different men to complete a painting of the tree that sheltered Buddha “under the skies of another country.” He thus acknowledges the different types of displacement at work among Asian Americans: Buddhism’s uprooting from its Indian origins and transplantation to Vietnam;the subsequent confrontation between the Vietnamese Buddhists of Orange County and the social chaos of Southern California; and the need for spiritual constancy reverberating in the Vietnamese diaspora after multiple Southeast Asian displacements. With a few deft strokes, Leong depicts the mostly male members belonging to the sangha of “Bodhi Leaves” as constantly renovating a fragile haven that shelters and sustains all its adherents, even if imperfectly and temporarily.

Faith, sexuality, and place are central concerns of both the writer and many of the characters he imagines. While Leong is alive to fleeting moments of Buddhist revelation – the aching purity of a lotus blossoming forth from the mud – he never slights the earthy realities of his characters or reaches for a na�ve spirituality by shirking examination of how it is that mud clings to the lotus in the first place, or that the dialectic of mud and lotus is founded in their intimate coexistence. The way sex and lucre or duty and self-actualization simultaneously dirty and ennoble each other, for example, can be found in the arrangement of the stories themselves. Mimosa and Haishan are two young Chinese women in “Daughters” who become prostitutes in America after their lives as well-kept mistresses to Taiwanese businessmen end. Their story invites comparison with the narrator in “Phoenix Eyes” who sustains a free-floating life for a time in Taiwan on the “international call line” of high-priced young men who “entertain” rich Western and Japanese businessmen. In “Hemispheres,” Bryan, an established gay filmmaker, considers requests to become a sperm donor from his women friends while at the same time he recalls the son he fathered years ago, when he had identified himself as bisexual.

The arrangement of the stories into three sections also works to thread together faith, place, and sexuality. The first section, “Leaving,” puns on the Bodhi tree leaves of the first story and announces the immigrant’s plight: the state of having always both just arrived and departed. The stories here meditate upon separations, whether being left by a lover, becoming lost in Golden Gate Park, or dropping into recollections of a lover from one’s past after ferrying one’s daughter to school. The second section, “Samsara,” sets the irony of sexual and other couplings, visceral and very basic forms of attachment, against the Buddhist notion of detachment. A man has sex with an old girlfriend as they both imagine her new boyfriend’s body. Two men find that love might be the highest-risk activity they can engage in, though sex comes easily.

The third section, “Paradise,” contains stories in which characters search for perfectly illusory places: marital happiness in the case of luckless Eddie Bin, spiritual quietude for an older man entering a Buddhist monastery and devastated by the loss of his many friends and lovers to AIDs. In the final stunning story, “Where Do People Live Who Never Die?”, what China represents and the absolute truth surrounding the mysterious death of one Chinese American man’s parents become intertwined and, in the end, impossible to recapture or revisit. In these and other stories, moments crafted by Leong of beautifully irreconcilable contradiction hark back to Gary Snyder’s poetic experiments with Buddhist thought at the same time that they extend contemporary Asian American prose fiction’s capacity to grapple with its underexplored legacy of pragmatic spiritual practice. ▼