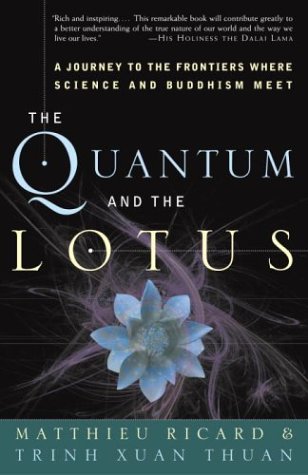

The Quantum and the Lotus:

The Quantum and the Lotus:

A Journey To The Frontiers Where Science and Buddhism Meet

By Matthieu Ricard and Trinh Xuan Thuan

Crown Publishers: New York, 2001

312 pp.; $25.00 (cloth)

Those of us who came of age in the 70s and were attracted to cool Eastern religions (and not to taking uncool hard science classes) didn’t get our physics Out of a textbook. We absorbed the work of Einstein, Heisenberg, and Bohr in an East-meets-West way, courtesy of two defining 70s tomes, Fritjof Capra’s The Tao of Physics and Gary Zukav’s The Dancing Wu Li Masters. We learned that when physicists use Einstein’s theories of relativity to measure the very large (the movements of galaxies and such), or Bohr and Heisenberg’s quantum mechanics to measure the very small (the locations of subatomic particles), the old Newtonian certainties about the objective nature of reality and the distinction between observer and observed begin to crumble. And so, Capra and Zukav told us, we’re left with a more fluid, holistic picture of the universe that has something in common with Taoism, Hinduism, and Buddhism. Groovy.

A quarter of a century later, the physics in those books has aged just fine (most of the really mind-bending stuff had been done by mid-centuty), but the loose generalizations about Asian spiritual traditions—what Capra insists on calling “Eastern mysticism”—seem less than satisfying. Now, in The Quantum and the Lotus, we have the remedy: a book that takes the form of an East-West dialogue between an American scientist and a Tibetan Buddhist monk. But the variables have been mixed up in an interesting way. The scientist, University of Virginia astrophysicist Trinh Xuan Thuan, was born and raised Buddhist in Vietnam. The monk, Matthieu Ricard, was a young avatar of French rationalism, a protege of the Nobel Prize-winning biologist Francois Jacob. In the early 70s, Ricard traded in his microscope for monks’ robes and a long Himalayan apprenticeship under two eminent Tibetan lamas, first Kangyur Rinpoche and later Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. (That was a heady decade.)

Thuan has written a well-received popular science book, The Secret Melody, but Ricard will probably be the more familiar name to readers. His book of photographs and recollections about Khyentse Rinpoche, Journey to Enlightenment, is considered a modern devotional classic. Three years ago, he stepped Out of the shadow of the Tibetan masters with The Monk and the Philosopher, a dialogue with his father, the eminent political philosopher Jean-Francois Revel, that reads like a Buddhist-humanist My Dinner with Andre and became a bestseller in France.

If The Quantum and the Lotus lacks the freewheeling quality of The Monk and the Philosopher—which manages to skate through all of Western philosophy and Buddhist thought in just three hundred pages—it is, in its own, more deliberate way, the equal of its excellent predecessor. By the time Ricard and Thuan have run Out of breath, we’ve gotten a crash coutse in modern physics and Tibetan Buddhist metaphysics and, more remarkably, have been dealt the strong suggestion that the latter anticipates the former at most every important turn. At the beginning of the book, Thuan frankly wonders if the two have anything to talk about. Buddhism, as he understands it, is about dlsophnmg the mind in order to live a saner and more compassionate life, while physics aims to describe physical reality-apples and oranges.

Ricard counters that Buddhism offers a compelling analysis of the material world: no part is objectively, inherently “real,” since every part depends on the whole for its more relative, interconnected reality. This same “there is no there there” analysis, applied to the individual ego, is the famous Buddhist formula for liberating the self from negative, selfish emotions. Thuan, in his own calm, professorial way, obligingly offers up the physics that allows Ricard to drive home his point. There is Einstein’s “thought experiment,” later verified in the lab, that shows two subatomic particles, miles away, somehow “knowing” which way the other will turn. At the macroscopic level, scientists have found that the most remote galaxies in the universe actually exert a measurable, if tiny, gravitational pull on a pendulum in Paris (“Foucault’s pendulum”). E. M. Forster’s dictum notwithstanding, we don’t have to connect, only wake up to the fact that we are connected.

So it’s a fine book, but I still miss Dad. One of the more compelling aspects of The Monk and the Philosopher, for non-monks and non-philosophers, anyway, was the spectacle of those two pillars of Gallic certitude, each loving the other (we’re told), neither wanting to bend an inch. Thuan is, by contrast, something of a pussycat. Whereas Jean-Francois Revel, the science booster, would have rejected our of hand the notion that” interdependency” (to use Ricard’s Buddhist term) at the atomic level has anything to do with human ethics or psychology, Thuan, the hard scientist, has an Oprah-esque “aha” moment: “So the interdependence of phenomena equals universal responsibility. What a marvelous equation!” I’m not plumping for disagreement for its own sake, exactly. It’s just that Ricard, with his steel trap scientific mind and his formidable command of Buddhist teachings (themselves case-hardened by centuries of debates with Hindu sages), is never pushed hard to question or defend his assumptions; the reader is left a little poorer for it. (Tradition-minded Tibetan Buddhists of the Nyingma school probably won’t mind at all.) On the other hand, when Thuan ventures beyond the physical evidence to suggest, as Einstein did, the existence of a grand design behind the universe (and by implication, the existence of a grand designer), Ricard cuts him to shreds logically, eliciting a surprised protest from the astrophysicist, who wonders: isn’t Buddhism supposed to be tolerant? The monk replies, “No matter how tolerant you are, you don’t have to accept other people’s metaphysical viewpoints.” ▼