Cultivating the Empty Field: The Silent Dlumination of Zen Master Hongzhi

Translated by Taigen Daniel Leighton with Yi Wu.

North Point Press: San Francisco, 1991.

91 pp. $11.95 (paperback).

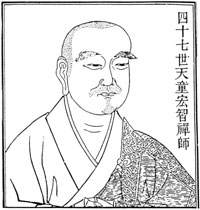

Silent Illumination, known to Western students primarily as “just sitting,” is usually associated with the Soto branch of Zen. But Eihei Dogen (1200-1253), credited with founding the Soto school in Japan in the 13th century and its most articulate spokesman, refused to recognize any such thing as a Zen school of any kind. The founder of Soto was thoroughly schooled in the “teaching story” tradition, that is, in koan study. Dogen’s predecessor, Chinese master Hongzhi Zhenguye (1091-1157), was the first to articulate silent illumination, a form of objectless meditation. Cultivating the Empty Field is a succinct anthology drawn from Hongzhi’s Extensive Record, a spiritual guidebook for the novice. In an excellent introduction, Taigen Daniel Leighton reveals the various philosophical threads that together weave the fabric of Zen, especially the influence of early Confucian ancestor worship and the ever-present Taoist view of yin and yang.

Hongzhi was concerned with the overemphasis on lineage and the grading of stages of progression. He called instead for a meditation completely free of grasping, that is, a meditation of “knowing without touching things,” a technique perfected only as one finds inward illumination and body and mind drop away. In Hongzhi’s view, enlightenment is not something that can be created, nor is it something that can be achieved. He refers the student to the fundamental teaching of Shakyamuni Buddha, that we are each enlightened already but permit false attachments to fool usthat we trick or confuse ourselves. Dogen concludes, “The study of buddhahood is the study of the self. Study the self to transcend the self.” In this translation, the short prose talks work very well indeed. The language is both simple and clear. On the other hand, the poetry, though adequate, remains pedestrian, going no farther than literal prose renderings broken into lines. Nevertheless, Cultivating the Empty Field is an inspiring little book and an important document in the Zen tradition.

While Chinese poetry and philosophy is loaded with metaphors drawn from nature, few poets employ metaphors in such an engaging manner as does Hongzhi. The empty field of the title returns again and again, more layered yet simplified in each context, from the empty field of nondiscriminating consciousness to the “dharma field that is the root source of the tenthousand forms, germinating with unwithered fertility.”

Leighton claims that “Hongzhi’s teaching presages such modern philosophical movements as Deep Ecology, with its sense of identity of self and ecosystem. It is not just that Hongzhi uses the cloud and mountain as metaphors (Leighton’s italics) for awakened activity; the clouds actually are us and the mountains are us [my emphasis], and also the fascination is us.” In fact, a great deal of what might be called ethical ecology is centered on an idea that parallels Buddhist ethics, defining both spiritual and cash economics in terms of interpenetrating, codependent systems. This “Buddhist ethic” is at work in the animal rights movement, in Deep Ecology, and in the struggle to save rain forests, old growth forests, deserts, and wetlands. It is alive in the physics of Fritjof Capra and in the essays of Wendell Berry and Barry Lopez. Hongzhi’s task is to help us awaken to an enlightened view of reality. Awakening to the vast empty field, we are the field.