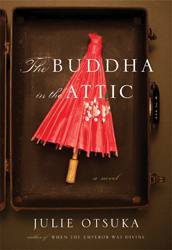

The Buddha in the Attic

Julie Otsuka

Alfred A. Knopf, 2011

129 pp., $22.00 cloth

Buddhist practice in America did not start with the Beats in San Francisco or the Transcendentalists in New England. The first American Buddhists were more l ikely ordinary Asian immigrants, first from China and later from Japan, Korea, and beyond. These laborers and merchants, farmers and domestics, planted the first seeds of the dharma that now bloom across the continent.

ikely ordinary Asian immigrants, first from China and later from Japan, Korea, and beyond. These laborers and merchants, farmers and domestics, planted the first seeds of the dharma that now bloom across the continent.

In her latest novel, The Buddha in the Attic, Julie Otsuka brings us the stories of one such wave of immigrants, the Japanese “picture brides” who sailed to San Francisco in the early 1900s. Crammed below deck in steerage class with what possessions they could carry (including a single photograph of the man they expected to marry), these young women left everything they knew behind for an alien and, as it turned out, often hostile land:

On the boat we carried with us in our trunks all the things we would need for our new lives: white silk kimonos for our wedding night, colorful cotton kimonos for everyday wear, plain cotton kimonos for when we grew old, calligraphy brushes, thick black sticks of ink, thin sheets of rice paper on which to write long letters home, tiny brass Buddhas, ivory statues of the fox god, dolls we had slept with since we were five, bags of brown sugar with which to buy favors, bright cloth quilts, paper fans, English phrase books, flowered silk sashes, smooth black stones from a river that flowed beneath our house, a lock of hair from a boy we had once touched, and loved, and promised to write, even though we knew we never would . . .

Otsuka’s unusual use of the first person plural continues throughout the book, and the resulting collective perspective brings us deep into her rich narrative of the immigrant experience as these women lived it. Not until the very end does she even use the women’s names. But despite the collective voice and the anonymity, these women emerge as individuals from the beginning. They are a diverse lot: farmers’ daughters, cultured young ladies from the city, a rich widow, a former dancing girl—some as young as 12 and 13. Yet nearly all sail with a dewy-eyed view of America as a place where “women did not have to work in the fields and there was plenty of rice and firewood for all.”

Reality hits with stunning force. Otsuka describes in almost brutal clarity the women’s first nights with the strangers who are now their husbands. And soon they’re scraping by in unfamiliar California, where there are “no bamboo groves, no statues of Jizo by the side of the road.” Most end up in the vast farmlands, where “the hills are brown and dry and the rain rarely falls. The mountains are far away.” And the locals are unwelcoming:

Sometimes they burned down our fields just as they were beginning to ripen and we lost our entire earnings for that year. And even though we found footsteps in the dirt the following morning, and many scattered matchsticks, when we called the sheriff to come out and take a look he told us there were no clues worth following. And after that our husbands were never the same.

Here, as elsewhere, that seemingly innocuous “sometimes” signals that there are many more such tales where these came from.

At just 129 pages, The Buddha in the Attic is brief but wholly absorbing, best savored gradually rather than devoured all at once. Though the language is exquisite, poetic, the subject matter is too wrenching, too poignant, to read in a single sitting. Each of the chapters reflects one step in the women’s stories, from their voyage to America up to the outbreak of World War II. Their lives can be unrelentingly difficult and bleak, “planting and picking tomatoes from dawn until dusk,” or living “eight and nine to a room behind our barbershops and bathhouses” in J-town, the Japanese ghetto. Much of the time their husbands are their only companions, but these postal marriages often disappoint, built on false promises mailed across the Pacific. Here Otsuka’s plural narrator becomes singular, leaping from one woman to the next:

My husband is not the man in the photograph. My husband is the man in the photograph but aged by many years. My husband’s handsome best friend is the man in the photograph. My husband is a drunkard.… My husband is shorter than he claimed to be in his letters, but then again, so am I.

The prejudice the Japanese immigrants face echoes with disconcerting familiarity. “They did not want us as neighbors in their valleys,” we’re told. “They did not want us as friends.” As happens to so many recent arrivals today, the newcomers are shunned because they “lived in unsightly shacks and could not speak plain English.” Though admired for their stamina, discipline, “and docile dispositions,” the Japanese are accused of creating unfair competition by gradually taking over the agricultural economy. In the cities, they fare little better, relegated to low-level jobs as domestic servants, gardeners, and cleaners. Like immigrants everywhere, they do the work no one else will do, and receive little thanks for it. They are forever outsiders, looking in. “We loved them. We hated them. We wanted to be them,” the women say of their well-to-do employers in the big houses of Atherton and Berkeley. That we know the story will eventually end happily for Japanese-Americans makes it no less anguishing to relive the degrading and often harrowing experiences of these first settlers.

The Buddha in the Attic can be read as something of a prequel to Otsuka’s first novel, When the Emperor Was Divine. Published in 2002, it is already a modern classic, required reading in many American high schools. Following the lives of several Japanese immigrants interned during World War II, When the Emperor Was Divine was based in part on the wartime experience of Otsuka’s family. (Her grandfather was arrested as a spy after Pearl Harbor, and her mother and several other relatives were sent from California to camps in Utah.) The Buddha in the Attic ends with the sad deportations that begin the earlier book, stopping short of depicting life in the camps. Instead, in the final chapter, “A Disappearance,” the point of view shifts eerily from the Japanese immigrants to their non-Japanese neighbors:

The Japanese have disappeared from our town. Their houses are boarded up and empty now. Their mailboxes have begun to overflow. Unclaimed newspapers litter their sagging front porches and gardens. Abandoned cars sit in their driveways. Thick knotty weeds are sprouting up through their lawns. In their backyards the tulips are wilting. Stray cats wander. Last loads of laundry still cling to the line. In one of their kitchens—Emi Saito’s—a black telephone rings and rings.

Otsuka illuminates this monstrous injustice, cataloging the resulting indignities, which are almost unbearable to contemplate. Yet these women did bear them somehow, just as other women had borne the casual discrimination and ignorance in the decades before. And they managed to maintain their faith not just in themselves and their families but, astonishingly, in the adopted country that had treated them so poorly.

Today’s American Buddhists owe much to these ordinary ancestors. (Not all of the picture brides were Buddhist, of course; Otsuka describes one “who was Christian, and ate meat, and prayed to a different and long-haired god.”) Several of the teachers who first popularized Buddhism among non-Asian Americans and established many of our present lineages initially arrived in this country to serve the local immigrant communities. The Zen masters Shunryu Suzuki and Taizan Maezumi began their American careers at Soto Zen temples in San Francisco and Los Angeles, respectively. It was the ethnic Japanese communities that first supported them in the 1950s and 1960s—communities that refused to give up on America, even after the internment years. Nyogen Senzaki, perhaps America’s first resident Zen monk, was interned during the war, but even he returned to Los Angeles after his release.

Near the end of The Buddha in the Attic, a few of Otsuka’s women finally acquire names, just in time for us to bid them farewell. Describing the day of deportation, Otsuka introduces Kimiko, who “left her purse behind on the kitchen table but would not remember until it was too late,” and Takako, who “left a bag of rice beneath the floorboards of her kitchen so her family would have something to eat when they returned.” Although we have not heard their names before, we know these women, having followed the strands of their lives that Otsuka has so deftly woven into this intricate and affecting novel. We are unlikely to forget Haruko, who, just before rushing from her California home to begin the long journey to the camps “left a tiny laughing brass Buddha up high, in a corner of the attic, where he is still laughing to this day.”