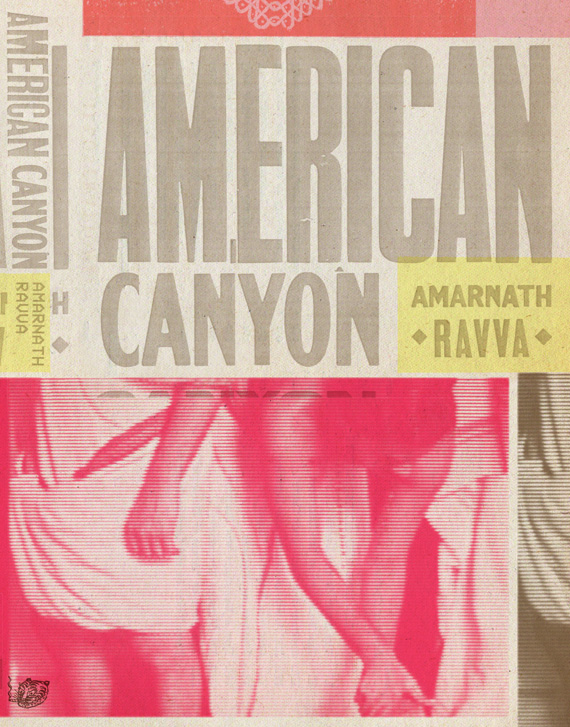

American Canyon

By Amarnath Ravva

Kaya Press, 2014

180 pp.; $23.95 paper

Amarnath Ravva’s snake was asleep. His mother’s seer, Sharma, who sensed from another continent the imbalance in Ravva’s body, diagnosed him. Sharma prescribes a visit to Livemore, California, for a homam—a Hindu ritual involving consecrated fire and offerings to the god Agni—where prayer is chanted; 1,001 ghee offerings are made; and Ravva’s name is written in Sanskrit on a piece of paper in which the pujari, or priest, seals ashes from the fire.

Did Ravva’s snake awaken? We readers are never told, nor are we informed what exactly this might mean. All Ravva knows is what he is told by seers and family members alike: this state of affairs is very bad, a great misfortune.

This is among the numerous anecdotes in American Canyon, Ravva’s fragmented rendering of family folklore and rituals he undertook in his “homelands” of California and southern India. “The American grain is a hollow trunk,” writes Ravva, who is American-born and of Indian descent. “Only the outer rings remain. . . . Our methods, our mechanical eyes and surgical hands treat symptoms because origins overwhelm us.” Ravva approaches ritual, and his recording of family history in the book, as a way of filling this chasm.

In undergoing such rituals, it is clear that Ravva is not indulging idle curiosity or merely going through the motions—something, we get the sense, is actually wrong. And though what is wrong with Ravva appears to be related to a “hollowness,” what precisely ails him remains mysterious throughout American Canyon.

It is this absence of explanation, of Ravva’s own interpretation of what he is being told and of the sacred rites he participates in, that makes the experience of reading American Canyon disorienting—and beautiful. Though well aware of his remove from the purported significance of these rituals, Ravva eschews the hackneyed narrative device of the hyphenated American suspended between two worlds, lonely, liminal, and lost. Instead, he employs precise descriptions of what he sees and hears, devoid of any value judgment or express indication of belief or disbelief.

“He lays out nine brass vessels. The largest, surya, is in the middle, with the other eight in a square around it. . . . He applies three red kum kum lines, eyes, to each of the vessels, then fills them with rice.” Here, Ravva recounts the preparations of a pujari conducting, for the author’s benefit, a naga prathista—a ceremony intended to address the karma he was told he assumed when, at some point in his life, his shadow fell upon a snake in the forest. Yes, at times reading such accounts can seem like reading a recipe for some unknown dish. But by stripping these depictions bare of his interpretation, Ravva transforms ritual into poetry.

The naga prathista, performed upon Ravva’s first trip to India in 10 years, is captured in part by video camera, and stills from the recording accompany the passages that describe the ritual. Though interspersed with similarly brief, episodic portions of family history and Hindu scripture, it is these passages that form the through line of American Canyon. The segments, marked with time stamps from the video, underscore that Ravva is perpetually more of an observer than a participant. The video camera, moreover, is a metaphor for the author’s anxiety about memory, or, more precisely, forgetting. He even persists in taping customary rites despite the disapproval of his aunt and the pujaris, who all try to remind him that these traditions are meant to be lived, not recorded. For Ravva, the combination of sound and image is supposed to fill the cultural gap—the canyon—between him and his Indian heritage, the hope being that he can at least preserve what he cannot understand.

His anxiety about being a lapsed inheritor of cultural memory triggers rare commentary from Ravva on the naga prathista. “I don’t deserve their efforts,” he writes. His Nayanamma—his paternal grandmother—says Ravva, would have been an apt recipient of these blessings. Ravva and his Nayanamma, according to his mother’s seer, share the same karma. Once upon a time, Nayanamma’s father killed a cobra that had slid into her sleeping area; the snake’s spirit, according to Ravva’s aunt, caused her first four children to die young. To atone, she traveled to a part of town where there was a huge hill overrun with snakes, and every day poured milk and honey on the ground. Subsequently, Ravva’s father and aunt were born, and they lived into adulthood. Nayanamma made milk and honey offerings to the snakes until she died.

Such family stories in American Canyon transition less jarringly to, say, Ravva’s fleeting reference to the Hindu god Rama’s siege on the shore of the southern sea with an army of monkeys. A term like “magical realism” might be applied loosely to categorize Nayanamma’s snake offerings, but Ravva’s rendering raises the question magical to whom? Whose story is discredited as “myth” or “tale”? Whose story is certified as “history”?

In American Canyon, Ravva’s largely judgment-free descriptive prose leaves family members and spiritual sages plenty of room to answer these questions for themselves. This is impressive, for one gathers that Ravva—having asked his mother how long the homam would take, admitting discomfort at the “OM” written in Sanskrit on his parents’ garage doors—is not particularly devout. If anything, he is more skeptical of the faith in industrialization and “progress” held by his uncle, a financial consultant on hydroelectric power projects, and his father, whom Ravva probes for supporting the use of DDT while housing Rachel Carson’s antipesticide appeal Silent Spring on his bookshelf.

Regardless of whose version of reality is deemed more or less credible, or celebrated or suppressed, it is clear that cultural memory cannot be wholly erased. This is not to deny that certain ways of being become obsolete, particularly in the face of what some call “modernization.” Ravva seems to feel that he is at the threshold of a disappearing tradition, one that he is unfit to carry on. Accordingly, many of his depictions are tinged with loss, as when, in India, he portrays a sodi—or spiritual medium—praying to gods unknown to him and describing “dying traditions with idioms and phrases long out of daily use, like her profession, which she is one of the last to practice.” It is true that the gorge of a canyon is the product of erosion, akin to how, as Ravva writes, “America has and continues to lose itself every day by the death of those who can still remember.” Yet in the wake of this loss, the evidence of what has worn away, of what has been buried, is preserved in the geographical layers of the canyon walls.

This embedded memory ultimately drives his mother out of the California home where Ravva grew up in Benicia to American Canyon. “Beneath our carpet, under the grey cement foundation, beneath a layer of trash, under thousands of years of historical conjecture, could be the bones of a Patwin.” His ailing mother had asked Ravva if any Native Americans had lived in the part of California now known as Benicia. She thought he might know since he’d recently gone to a Maidu Bear Dance. (“The Indian American had met the American Indians in the Sierras and found some kinship.”) On account of this concern, and some irreparable violations of vaastu—an Indian form of feng shui—she became convinced that all their troubles were tied to their house in Benicia.

Ravva’s mother, as they were told by a seer, was haunted by an indigenous ghost, a spirit that was draining her lifeblood. And so it is, toward the end of American Canyon, that portions of Native American history—specifically, the genocidal elimination of indigenous Americans from Californian land—are interposed with Ravva’s anecdotes of family and ritual. While the linkages between these and other fragments are not made for us, again, these stories present a paradox: both the aftermath and impossibility of erasure.

Even the film with which Ravva anxiously records his latest trip to India is a kind of palimpsest. Prior to this trip, the last documented in American Canyon, Ravva writes that all his DV tapes of earlier visits to India were lost, “leaving only the fading images in [his] memory.” Though the “digitized transmission of history” is lost to him, he still figures that even if the drive has been erased, this will have destroyed “only the surface index, not the binary code that marks the instances of magnetic repulsion and attraction that lie beneath. Behind the veil of its emptiness, a small town in India still remains.”

In the end, Ravva seems to concede that, like the video camera he uses to record the naga prathista, when it comes to his Indian heritage, he is capable of passing on only a “false record—one that was discontinuous and incomplete.” The disjointed structure of American Canyon stays true to this concession. But perhaps, as the book suggests, one’s heritage or history still leaves a trace, a memory that is independent of conscious awareness. Even if, as Ravva’s pujari put it, he had “the misfortune of being born in America,” his ancestry lives on through him. Snakes and all.