Iconoclasts often fare badly in their lifetimes, their genius acknowledged only later on. Such was the fate of Gendun Chopel, a scholar, artist, and activist who now, six decades after his death, is a cultural hero to Tibetans both at home and in exile. Born in 1903 and trained in the Nyingma and Gelug traditions, Gendun Chopel traded in his monk’s robes in the mid-1920s to travel extensively in southern Asia, the first Tibetan to set foot in what is now Sri Lanka. Steeping himself in other languages and cultures, he recorded his research, observations, and insights in a lavishly illustrated volume he considered to be his life’s work. It was intended to introduce the insular Tibetans to the ways of the modern world but instead was rejected. Gendun Chopel’s words remained unread until 1990, when a momentary relaxation of Chinese restrictions on Tibetan literature allowed the manuscript, sans artwork, to be published. Now, Grains of Gold: Tales of a Cosmopolitan Traveler (University of Chicago Press, January 2014, $45, 456 pp., cloth), is available in English for the first time, translated and introduced by Geshe Thubten Jinpa, the Dalai Lama’s translator, and scholar Donald S. Lopez, Jr. The few extant illustrations are included.

Iconoclasts often fare badly in their lifetimes, their genius acknowledged only later on. Such was the fate of Gendun Chopel, a scholar, artist, and activist who now, six decades after his death, is a cultural hero to Tibetans both at home and in exile. Born in 1903 and trained in the Nyingma and Gelug traditions, Gendun Chopel traded in his monk’s robes in the mid-1920s to travel extensively in southern Asia, the first Tibetan to set foot in what is now Sri Lanka. Steeping himself in other languages and cultures, he recorded his research, observations, and insights in a lavishly illustrated volume he considered to be his life’s work. It was intended to introduce the insular Tibetans to the ways of the modern world but instead was rejected. Gendun Chopel’s words remained unread until 1990, when a momentary relaxation of Chinese restrictions on Tibetan literature allowed the manuscript, sans artwork, to be published. Now, Grains of Gold: Tales of a Cosmopolitan Traveler (University of Chicago Press, January 2014, $45, 456 pp., cloth), is available in English for the first time, translated and introduced by Geshe Thubten Jinpa, the Dalai Lama’s translator, and scholar Donald S. Lopez, Jr. The few extant illustrations are included.

Visiting India at a time of strong anticolonial and nationalist sentiment, Gendun Chopel observed what he called the “racism, greed, and mendacity”—and thus the danger—“at the heart of the colonial project.” His far-seeing work incorporated modernity into the classical Tibetan worldview in what the translators call a kind of “modern classicism.” He used the methods of modern scholarship brought by the colonialists to warn his countrymen of their bearers’ malevolence.

Like Gendun Chopel’s peregrinations across the subcontinent, Grains of Gold rambles through a vast array of topics, from science, technology, history, and linguistics to ethnography, biology, and comparative religion, interspersed with the author’s poetry. Other passages fit more neatly into the travelogue genre. In Sri Lanka, Gendun Chopel’s encounter with Theravada Buddhism, which he had only read about and debated as a monk, elicits thoughts on what happens when “vehicles” collide. In India, he recovers lost histories of Tibet, “permeated by Indian influence as a sesame seed is permeated by its oil, so much so that when it is necessary to provide a metaphor in a poem, only the names of Indian rivers, mountains, and flowers are suitable.” After his efforts to bring his compatriots up to date failed, Gendun Chopel died a broken man at 49, just weeks after the Chinese invaded Tibet. We today can appreciate the significance of his work. As the translators write, it “engages modernity, in its complex forms, more fully than any work in Tibetan literature.”

Donald Lopez’s scholarship is also central to another new volume,The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism (Princeton

University Press, November 2013, $65, 1,384 pp., cloth), written and edited by Lopez and Robert E. Buswell, editor of The Encyclopedia of Buddhism. With more than 5,000 entries, the dictionary is the most comprehensive English-language compendium of Buddhist terms to date. Buttressed by appendixes, cross-references, maps, and a timeline, the entries range over canonical terms, concepts, texts, schools, monasteries, geographical sites, and key Buddhist figures—even some Orientalist scholars. Entries like the one for the notoriously difficult-to-explain term dharma elaborate on the basic definition with detailed etymologies, context-dependent variations, and pre-Buddhist origins and usages. While most of the terms are Sanskrit, they are cross-referenced in all canonical Buddhist languages—Pali, Tibetan, Chinese, Japanese, and Korean, as well as Sanskrit—providing one of the new encyclopedia’s most useful features. Supplements include a 37-page “List of Lists,” a collection of all the mnemonics we never properly memorized. Fours take the crown for most mnemonics in the Buddhist religion, from the four absorptions to the four tantra classes.

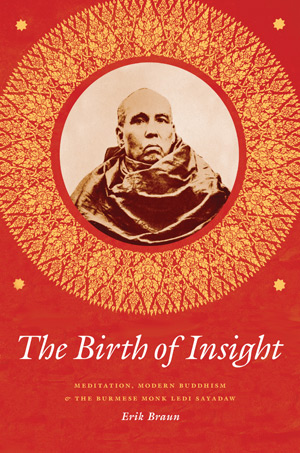

Popular Buddhist works reassure us that anyone can meditate and anyone can benefit from the practice. But it was not until the early 20th century in Burma, the “Golden Land” of Buddhism, that meditation went from a practice of the few to a mass movement. InThe Birth of Insight: Meditation, Modern Buddhism, and the Burmese Monk Ledi Sayadaw (University of Chicago Press, 2013, $45, 280 pp., cloth), scholar Erik Braun traces the emergence of Vipassana, or insight meditation, as a widespread practice to Ledi Sayadaw, a learned and charismatic monk who became one of the most popular teachers in Burma’s history. Born in 1846, he was an early proponent of meditation for householders, teaching abstruse texts in a down-to-earth, entertaining, and sometimes humorous fashion that consistently attracted throngs of nonmonastics and made his writings best sellers.

Popular Buddhist works reassure us that anyone can meditate and anyone can benefit from the practice. But it was not until the early 20th century in Burma, the “Golden Land” of Buddhism, that meditation went from a practice of the few to a mass movement. InThe Birth of Insight: Meditation, Modern Buddhism, and the Burmese Monk Ledi Sayadaw (University of Chicago Press, 2013, $45, 280 pp., cloth), scholar Erik Braun traces the emergence of Vipassana, or insight meditation, as a widespread practice to Ledi Sayadaw, a learned and charismatic monk who became one of the most popular teachers in Burma’s history. Born in 1846, he was an early proponent of meditation for householders, teaching abstruse texts in a down-to-earth, entertaining, and sometimes humorous fashion that consistently attracted throngs of nonmonastics and made his writings best sellers.

Historically, Buddhism in Burma centered on devotional practice, with monks acting as “fields of merit” for the laity, who could generate good karma by giving alms. But in the 19th century, Braun explains, British colonial influences challenged the importance of the monkhood in Burmese society. To protect Buddhism from colonial sway, Ledi reformulated teachings and reconfigured Burmese Buddhist institutions for the modern world, empowering householders to study and meditate. After all, if the masses were well versed in Buddhism, he reasoned, the British would be powerless to destroy it.

Ledi Sayadaw’s creative response to colonial pressures harked back to precolonial values and traditional emphasis on scriptural authority. In telling the unlikely story of how Buddhist meditation in Burma became a vaguely patriotic pastime, Braun establishes a dynamic continuity between traditional and modern practice.