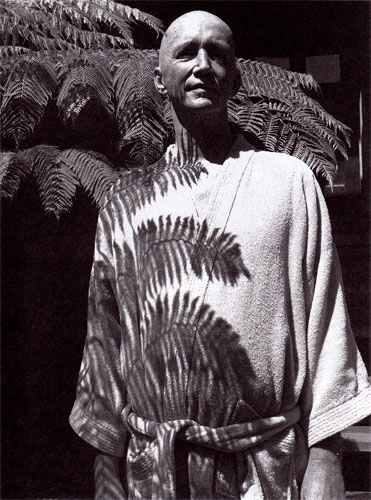

Issan Dorsey, who died of AIDS two years ago in San Francisco at the Zen temple/hospice he had founded, was an unlikely bodhisattva. His journey had not taken him through a series of serene Asian monasteries but through American bars, clubs, back rooms, and communes. By the time he became the abbot of One Mountain Temple (also called the Hartford Street Zen Center), Dorsey had practiced Zen meditation only slightly longer than he had worked in show business—mostly on stage as a female impersonator.

Born Tommy Dorsey in 1933 to a working-class family in Santa Barbara, Dorsey says, “My parents had no idea what they were doing. They were about twenty-one when I was born. They were expecting a macho little boy, and they got a sissy.” Instead of going out for baseball or joining the scouts, Dorsey studied dance and piano to advance his dream of becoming an entertainer. He scuttled the plans for the priesthood, that the local nuns held for him, but he also found attending the local junior college unbearable. Feeling the pressures of his nascent homosexuality, Dorsey ran away and joined the Navy. This got him out of his parents’ house and into the world of men. The Navy also offered him the opportunity to work as an entertainer, and he took it, performing in shows on the base and on television specials in Los Angeles.

Dorsey soon found a lover. And both were soon expelled from the service and flown home from the Korean War for “failing to ask permission to be a Navy couple.” They were discharged in San Francisco, as were hundreds of gay men over the years. After some bitterly frustrating years trying to fit in “straight” jobs downtown, Dorsey found employment in a North Beach bar, first as a waiter, then as a host, and finally as a performer in the drag revue. He turned out to be an enormous crowd pleaser—so good, in fact, that he was invited to join a traveling road show called The Party of Four.

In the sleazy nightclub world of the late 1950s, female impersonators often performed additional services, functioning as bar-girls (encouraging customers to keep drinking) or as outright prostitutes. Hard drugs also exacted a toll in this lifestyle. When Dorsey returned to San Francisco in the mid-1960s, he was a self-described “mess.” The city itself, however, was bubbling with new energy, which would soon blossom in the Haight Ashbury section in the form of Flower Children, the summer of love, the San Francisco sound, and “human be-ins.”

Dorsey cleaned up his drug habits, founded the first San Francisco urban commune, and managed a rock band. The commune supported itself handsomely by selling the softer drugs of psychedelia, but for a serious junkie like Dorsey, this seemed a step in a positive direction. Surrounded by the happy melange of altered states and spirituality that prevailed at the time, Dorsey found himself practicing Zen meditation one morning, under the guidance of Japanese Zen master Shunryu Suzuki Roshi.

Twenty-one arduous years after he had showed up for morning meditation with “long hair, barefoot, dirty, high, and wearing beads—the whole mess,” Dorsey became a Zen master in his own right. Suzuki Roshi’s senior disciple Richard Baker Roshi certified Dorsey, now called Issan, as an authentic teacher and living representative of Buddha’s lineage. Issan assumed the abbotship of the Hartford Street Zen Center in 1989. He had nurtured this group from its earliest meetings as the Gay Buddhist Club into a full-fledged Zen outfit, complete with temple and residence in San Francisco’s Castro district.

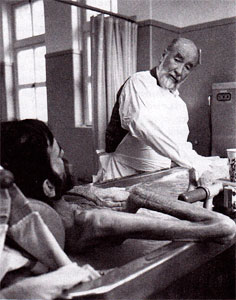

At the same time, he had been paying close attention to developments in the gay community and began volunteering time at Coming Home Hospice. The AIDS problem was so severe, he felt that everyone would have to do something. Consequently, when one of his Zen students manifested advanced symptoms of AIDS, Issan installed him in a room in temple quarters. Unofficially, Maitri Hospice was born.

An inveterate finagler, Issan calculated that with the young man’s SSI allowance and his allotted hours of attendant care from the county, it would be just as easy to house two disenfranchised AIDS sufferers as one, pooling the hours of attendant care. When a soft-spoken, HIV-infected Haitian man named Bernie joined the temple population, Issan could no longer pretend he wasn’t running a hospice.

Though socially and religiously laudable, the hospice overlay on temple life disturbed many members. Nearly all the residents were gay men, each one struggling already with the ineluctable question of AIDS and what his relationship with it might be. For many, inviting AIDS into the living room brought it too close. They’d bargained for a Zen center—they’d planned, and fund-raised, and built a Zen center—not a hospice. By the time Issan convinced his old friend Steve Allen to help, all but one temple resident had moved out.

Undiscouraged, Issan plowed ahead, engaging many old Zen Center associates to pitch in: one with fundraising, one as medical director, another as carpenter and property consultant. Forming an extensive network of support, he forged working relationships with volunteers from other hospices and from the gay, medical, and Buddhist communities. Within a year, Issan obtained a ten-year lease on the house adjacent to his temple. Filling it with men dying of AIDS, he arranged a continuous schedule of attendant care—this along with a vigorous practice of Zen meditation, classes, and lectures.

The years Issan spent “on the street” inspired him to look at people in that life with a direct, personal compassion. The fact that he’d grown up in a large family and had always lived as part of a group—a road troupe, a commune, or a Navy ship—accounts for the decidedly homelike environment he created in the hospice. Years of Buddhist meditation gave him the centeredness and freshness of mind necessary to take on a project as fiscally and emotionally impossible as a hospice. But another factor forced his meditation on death out of conceptualizations, and into actual practice: Issan himself developed AIDS. At his last lecture, he said, “The encounter with death begins at birth, not when we are actually sick and dying. Baker Roshi, my teacher, had me speak about the fact that it should be our practice to keep in front of us, all the time ‘I certainly am going to die. I certainly am going to die.’

“When I was listening to his lectures, I always said, ‘Oh, I understand that. I know that,’ because I had been close to death many times in my life. Also I had already begun some minimal work with people with AIDS. In my mind, I felt I understood what that meant—’I certainly am going to die.’ But lo and behold, when I had my HIV test in Santa Fe, and it was positive, the relationship with ‘I certainly am going to die,’ changed. Radically. And then all along the way. . .

“It’s too bad that it took such an epidemic for us to begin to think this way. That we have not only the opportunity, but the responsibility to spend time with people who are dying. Probably my great-grandmother had her whole family with her when she died. But my grandmother died in an old-age home.

“‘I certainly am going to die.’ It’s something we could meditate on, keep in front of us all the time. Not with sadness, but just…Somewhere along the way we came to think it was unfortunate to be sick, and to get old, and to die. If sickness, old age and death are unfortunate, then so is birth.

“To keep in front of you ‘I certainly am going to die,’ all the time. We forget. Even now, if I have a few healthy days in a row, my whole attitude changes, until all of a sudden I get another little ckkch! (makes a jabbing motion) saying, ‘Hey, you certainly are going to die.’

“I find it fascinating, and curiosity is there, too. Also, fear. It’s interesting to own that and not to think ‘I’m a Buddhist priest. I’ve been sitting for twenty years, when death comes, I’m just going to slide right out of there.’ (laughing) You know, I don’t know if I’m going to go out kicking and screaming. Most people who die at our house die pretty well, don’t they? I’m encouraged for myself. As I see people get very sick—young people getting very sick, and see how well they do it—it makes me feel bad that I complain and groan so much over my little loss of energy and anxiety attacks and sicknesses that I received from the medicines. I do that and then I see these young kids doing it so well.”

During his last week Issan knew that he would die at any moment. According to one doctor, it was simply a matter of which major organ his cancer would strike first. He used the time to receive an unlimited stream of visitors and to transfer the responsibilities of being abbot to Kijun Steve Allen. When Issan died at home, in the hospice, on September 21, 1990, he did it “very well,” as it turns out, surrounded by friends and practitioners. According to Steve Allen, who had actually climbed into the bed to hold him, Issan had one tough half hour, right before the end. During this time, his breathing became exaggerated and his limbs shook quite a bit. Then he got very calm, very relaxed, took five or six even breaths and stopped.

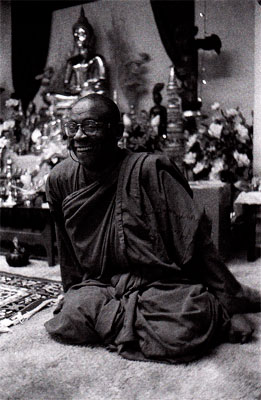

Unlike Issan, the Reverend Suhita, who prides himself on being “the first Afro-American ordained in all three traditions of Buddhism,” never intended to work with AIDS patients. When he opened the Metta Vihara in an industrial section of Richmond, California, Suhita (born Anthony Smith 50 years ago) intended to combat homelessness. It just turned out, he says, that the first two homeless men he took in had AIDS. Once word got around that Suhita—which means “good heart of wisdom”—would accept HIV-positive people, other health care institutions, including local hospitals, began sending patients to the Vihara. In fact, says Suhita, “They began to dump people on us. Sometimes these people would have terrible problems we were told nothing about. We would only find out later.”

Suhita got an early start in his vocation. At the age of 14, inspired by reading Thomas Merton, he set out for the Guadeloupe, a Trappist monastery in Oregon, where he lived as a monk for the next ten years, working in the infirmary. With the blessings of the Roman Catholic Church Council known as Vatican II, Suhita studied Buddhism in Thailand, Vietnam, India, Nepal, Bhutan, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Presenting himself as just a monk, he stayed and practiced in monasteries wherever he went: “Thomas Merton once said, ‘Monks are monks, regardless of religion.’ And it’s true.” Suhita took ordinations in the Theravada, Mahayana, and Vajrayana traditions, and he also visited Jain and Coptic monasteries.

Ironically, Reverend Suhita met his real teacher back in Los Angeles: the Venerable Thich Thien An, the first Vietnamese Buddhist to live and teach in America. In the span of one week in 1975, the United States government had allowed close to 100,000 Vietnamese refugees to immigrate. Suhita was sent to Fort Indian Gap Town Camp, near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to work in the Vietnamese refugee camps established there. Over the next several years, he served as chaplain in numerous such camps around the country. Setting up temples, he took care of the sick and old—whatever was needed. With dark skin and Buddhist robes, refugees assumed that he was Sri Lankan, or Thai.

In the early 1980s Suhita began working with the disenfranchised and homeless in Los Angeles. When Dr. Thien An passed away in 1981, he established his own temple in the Bay Area. Of his small house in Richmond, he says, “Wherever a monk stays, that becomes a vihara, so I decided to call my place the Metta Vihara.” (Metta means “friendliness” in Pali.)

In the black community, AIDS moves much more through the needle (and sexual partners of needle users) than through unprotected homosexual sex, so in his work Suhita often sees whole families infected, parents and children. As opposed to socialized, highly organized, white male homosexuals, many substance abusers, particularly in the black and Hispanic communities, view government services with distrust. Suhita often accompanies his charges to make sure they actually get to appointments, collect money, medication or benefits. Even with a slim crew and scant resources, Suhita has expanded his hospice program to three houses full of patients. He would also like to provide a complete line of Buddhist social services, including a hospital. “That’s probably my Roman Catholic upbringing showing through,” he says, chuckling. “The tradition of service.”

Though his vision may be grand, Suhita’s actual approach to AIDS is very intimate. “You can’t treat everyone the same, because the virus affects each one differently. You have to deal with it one-to-one.”

Zen Center Hospice—by far the largest and most fiscally stable of the three Bay Area hospices—was not inspired by one fervent monk standing in the midst of deplorable conditions. This hospice grew instead from a communal background of caring for people who died at Zen Center, starting with Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, founder and first abbot, who died there in 1971. Gregory Bateson died at Zen Center; so did Alan Chadwick, Lama Govinda, and a number of lesser known practitioners and friends. The value of spending time with people through their dying was evident to those who had done it.

As part of a carefully conceived plan, Zen Center began a training program in 1987. The program sought to provide qualified workers for hospices already in place. Director Frank Ostaseski soon linked the training program to hospice units in two large San Francisco hospitals and to smaller hospices as well, including Maitri. Last year, Zen Center Hospice provided 20,000 hours of service, caring for 250 people who died from AIDS or cancer; they also opened their own four-bed hospice in a large Victorian house across the street from the Zen Center.

Volunteers have often been dramatically affected by the program: one went on to become medical director of a hospice/AIDS unit at Laguna Honda Hospital; another became assistant medical director of the Hospice of San Diego; yet a third now provides AIDS education to prostitutes in Thailand. The two most recent directors of Maitri Hospice graduated from the Zen Center training program.

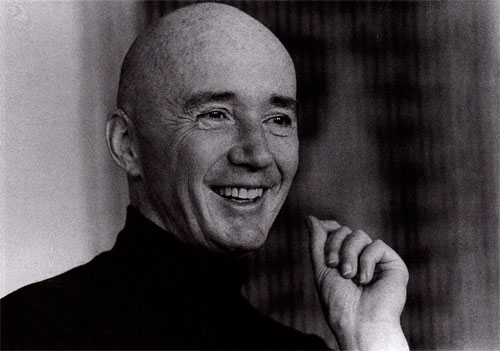

Though all volunteers are asked to have a meditation practice of some kind, the spiritual component here is not particularly stressed. Working in hospitals instead of home environments, dealing with seven-figure fund-raising efforts, and handling extremely complex logistics precludes an entirely spiritual approach. “The religious quality is there,” says Norman Fischer, chairman of the hospice’s board of directors, “but at this point, it’s more like an arm, instead of a heart, or the whole body. That’s just part of the price for having a big, efficient operation.”

Paul Haller, another senior Zen Center monk involved with the hospice, offers a different perspective. “When you are actually sitting there with someone who is dying, it raises all those heavy questions for you: What is going on here? How will I die? Am I afraid of death? What can I do? These are profound, immediate questions, and there really isn’t any getting around them. The very nature of the work undercuts any ideas about it. That’s one of the reasons we’ve been able to settle with it.”