Akase padam natthi, samano natthi bahire,

Papancabhirata paja, nippapanca tathagata.There are no footprints in the sky;

You won’t find the sage out there.

The world delights in conceptual proliferation (papanca).

Buddhas delight in the ending of that (nippapanca).Akase padam natthi, samano natthi bahire,

Sankhara sassatta natthi, natthi buddhanam injitam.There are no footprints in the sky;

You won’t find the sage out there.

There are no eternal conditioned things.

Buddhas never waver.(Dhammapada 254–255)

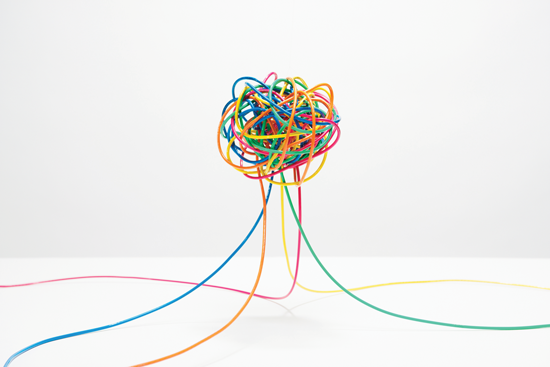

The Buddha taught that the generation of suffering is intimately connected to the process of perception, particularly the way in which we relate to thinking. When concepts and thoughts are entertained without wisdom, the world becomes fragmented and filled with complexity. The Buddha called this tendency papanca, or “conceptual proliferation.” A simple thought like “me” gives rise to a “you.” A “this” necessitates a “that.” As conditions change, the notion of time is created. The actual flow of sense experience is ever-changing and ungraspable, but the nature of language imparts apparent solidity and “thingness” to the world. When thought and concept are thus conjoined with ignorance, it leads to grasping, proliferation, increasing complexity, and the suffering of endless “birth and death.” We think, for instance, that we’ve attained something solid, like “my happiness,” but instead we’re left with perpetual frustration, bound by the mercurial, discriminating mind.

Our true nature is like the infinite sky, unmarked by whatever drama temporarily appears in its vast space. The heart remembers its essential spaciousness. Heedless thinking complicates, entangles, and traps the sense of “me” into sticky webs of suffering. Mindful of a thought, like the momentary glimpse of a colorful sunbird flashing through the light, the heart remains undisturbed, serene in its sky-like presence. Whatever the circumstance, bodily movement or stillness, feeling well or distressed, with good concentration or scattered attention, everything can be brought back to awareness.

The ending of papanca—nippapanca—reveals the true, undivided nature of the reality we inhabit. When the proliferating tendency of the mind ceases, even for a moment, the everpeaceful radiant heart is recognized. Papanca means “to spread out,” and the word conveys the dynamic web of thoughts and concepts that create our sense of reality. Rather than illuminating reality, papanca actually eclipses the direct seeing of what is really true. Papanca endlessly separates, and nippapanca means the cessation of that. It is a profound practice, to see through thinking and its activity of concretizing the self and the world. This is done not by hating thought, but by mindfully noticing a thought, particularly its beginning and ending.

In our early monastic retreats decades ago, Ajahn Sumedho, the senior Western monk of the Thai forest tradition, taught us the transformative technique of using thought to consciously explore its nature. He instructed us to take any thought, like “My name is . . . ,” and slow it down. In those moments, rather than heedlessly thinking about this and that, there is a conscious reflection on thought itself, and its origin. For a moment it is possible to see thought as just thought, a vibrating perception that arises out of silence and returns to silence. Usually thought is part of a phrase, a sentence, a paragraph, and a story, a whole enchanting framing of reality.

Ajahn Sumedho would encourage us to notice the gaps between the thoughts. “Mind the gap,” he would say, playing off the loudspeaker warnings in the London Underground. In this radical reflection, we were invited to plunge into the gap, returning to the source, the gateway to the mystery. As we realize the true empty nature of thought, we begin to experience the whole, undivided wonder of the moment, undistorted by papanca.

What is the quality of presence when there is no thought? This is a powerful contemplation. Try it! While the narratives and descriptive processes of thought have their place, they are endless. Papanca is described in the Lotus Sutra as “a yak being enamored with its tail.” We feel we can capture something by thinking about it. In reality, when we grasp at thoughts, the very process of trying to possess a piece of life ensures that it continually eludes us. We can never hold on, so the thoughts go round and round.

The transformative power of a conscious, mindful thought is that it reveals its own transiency. For example, the thought “Who is thinking?” is an invitation to make contact with the present moment. In doing so, the thinking process is recognized for what it is. When we’re not so enchanted by our thoughts, we notice something else, something quite simple. We notice that all thoughts manifest and dissolve back into silent listening. This is a great relief. We don’t have to become shaped by our thinking. We can be liberated from its bondage. In seeing thought as “just thought,” the sky of the heart is revealed, with no footprints. “You won’t find the sage out there.” When there is wisdom, the endless searching for happiness “somewhere else” vanishes. Where is there to go? Beautiful thoughts and ugly thoughts, all arise and cease in awareness, and yet awareness remains unmoved.

Awakening means a fundamental shift takes place. It is a shift from looking for ourselves outside in the ten thousand things to recognizing that our true nature is beyond definition. That transformation of understanding is the work of wisdom, the essential quality of heart that carries us across the turbulent sea of suffering to safety and ease. The Buddha refers to this liberating activity as Yoniso manasikara. It is often translated as “wisely reflecting.” Yoni means “womb” and manas refers to the mind. Taken as a whole we can interpret the phrase as “placing the mind and its activities in the womb of awareness.” Wise reflection does not stop at the superficial cognition of the world, but it plumbs the depths of awareness, exploring the unmoving ground of “knowing” within which all the apparent differences of life manifest. I like the English translation “radical reflection” for this significant term, since it echoes the “re-membering” of all phenomena to its source, the matrix of awareness that makes all experience possible. The word radical has its etymological connection to root. Radical reflection contemplates the root, the origin, the place where all things merge.

The Buddha emphasized the abandoning of papanca as essential to the realization of nibbana. When Sakka, king of the gods, approached the Buddha (DN 21) to inquire why beings wanting peace and harmony end up living in conflict and hate, the Buddha traced the causes back to papanca. When there is papanca, thinking arises, and with thinking comes desire. Desire gives rise to like and dislike. Like and dislike lead to envy and stinginess. And envy and stinginess create the conditions for conflict and hate, even though there was an original wish for peace and harmony. The Buddha instructs Sakka:

Now, of such [wholesome] happiness as is accompanied by thinking and pondering, and of that which is not so accompanied, the latter is the more excellent. The same applies to unhappiness, and to equanimity. And this, ruler of the gods, is the practice . . . leading to the cessation of papanca.

Practices For Radical Reflection

ONE

Sit in a comfortable position, and bring your attention to the present moment. Take a few long, mindful breaths. Consciously savor the bodily sensations of breathing in. Relax and let go as you mindfully breathe out. Letting go with each out-breath, steady awareness on the sensations of the body. Notice the changing nature of sensations. Holding those sensations lightly, rest in the spaciousness of awareness. Consciously think a thought related to the present moment, like “I am sitting” or “I am aware.” Choose an ordinary thought that isn’t emotionally charged. Think the thought slowly and mindfully. Notice the silent moment before the thought appears. Be mindful of the inner words as they fluctuate, vibrate, and dissolve. Contemplate the quality and texture of the inner voice as it manifests and changes. Be aware of the ending of the thought. Be mindful of the space after the thought, before the next thought arises. Mind the gap. Savor the moments between thoughts. Although thoughts begin and end, ask the question “What remains?”

Repeat the process again and again. Slow the thoughts down, so that the ephemeral nature of concepts is clearly recognized. In this practice, remember we are not thinking in order to arrive at an answer. Rather, we are consciously thinking to reflect on the nature of thought, noticing how it arises and ceases within the stillness of awareness. Contemplate how each thought is insubstantial and empty of solidity. What is the mind like when there is no thought? Extend the spaces between thoughts.

Consider how each word and phrase dissolves into silent inner listening. Sense how the inner listening—awareness, the knowing—is spacious without boundary. Like lightning in a night sky, concepts appear and then vanish.

TWO

Link a simple thought to the breathing. A quiet thought like “In” as you breathe in, and “Out” as you breathe out. Or “Let,” while breathing in, and “Go” while breathing out. It can be any thought that helps you stay present. Notice the thought dissolve into listening. Relax on the out-breath and sense the subtle relaxation of volition as the thought disappears. Practice letting the mind rest quietly between thoughts. Hold the thoughts more and more lightly, perhaps just having a quiet thought on the out-breath, “Let go,” and abiding in inner silence until the next breath. Practice letting thoughts subside, sitting with the body breathing.

THREE

Ask the question “Who is thinking?” Notice how the attention turns inward to look for the sense of me. Stay with the feeling of doubt. Notice how the question stops the thinking mind. Linger with the sense of silent questioning. If the mind throws up an answer, notice that thought in its changing insubstantial nature, dissolving back into listening.

The question “Who?” is held lightly and sparingly. If the feeling of doubt is too coarse and uncomfortable, balance it with the thought “Let go,” reflecting how all thoughts are ungraspable. Remind the heart to rest in its own spacious awareness. “Who” can be combined with a variety of endings, depending on what is appropriate: “Who is worrying? Who is practicing? Who is suffering?” and so on. The ending is not so important, but “Who” encourages the heart to question the primal split of subject and object, in here and out there.

To empty the sense of things out there, use the question “What? What is it?” The ordinary habitual mind might be telling us it’s good or bad, painful or pleasant. Slowly think the thought “What is it?” Let the question lead you to the undivided stillness of listening.

Think the thought “What remains?” or “What never waivers?” While noticing the flickering, ever-changing nature of the thought, silently ponder the womb of awareness within which all phenomena appear.

FOUR

An obstacle to this practice is the assumption that thought itself is the problem. Thinking, tainted with delusion, complicates and obscures reality. The Buddha still used thought, but without papanca.

In a daily activity, like walking or eating, quietly think a thought, noting the activity. It can be a simple word or phrase—“Walking,” “Eating.” Let the word dissolve, directing attention to the activity. Practice being with the activity in inner silence. Notice how often the mind wants to think and discriminate. Without judgment, just patiently recognize that, allowing each thought to return to stillness. Is it possible to be with activity, with less and less thought, enjoying the silence?

FIVE

How is it when the heart is silent? Notice how the complicated walls of the mind dissolve when conceptualization is absent. Undifferentiated, the senses merge and things are just as they are. Practice inviting opinions about yourself or the present moment, thinking them slowly: “I’m great; I’m a basket case; It’s easy; It’s difficult.” Let each concept, seemingly so true and real, be known as evanescent, continually vanishing into unmoving, sky-like awareness. Notice the shimmering stream of vibrating sensations, sights, sounds, and perceptions. How can thinking capture reality?

As the Buddha says in the Lotus Sutra, “This reality cannot be described. Words fall silent before it.”

♦

Main text adapted from Listening to the Heart: A Contemplative Journey to Engaged Buddhism, by Kittisaro and Thanissara, published by North Atlantic Books, © 2014 by Kittisaro and Thanissara (H. R. and L. M. Weinberg). Reprinted by permission of publisher. Practices written originally for Tricycle by Kittisaro, a former monk in the Thai forest tradition who is cofounder, with Thanissara, of Dharmagiri, a hermitage in South Africa.