Shaolin: Temple of Zen

Justin Guariglia

New York: Aperture Foundation, 2007

144 pp.; $40.00 (cloth)

American Shaolin

Matthew Polly

New York: Gotham Books, 2007

384 pp.; $15.00 (paper)

BODHIDHARMA IS ZEN’S founding father. As its first patriarch, he carried the lamp of enlightenment eastward from India to sixth-century China, where it would eventually spread to Vietnam, Korea, Japan, and beyond. He is immortalized in the daily lineage recitations of countless Zen monks worldwide, and in their silent struggle with the master’s great life koan: Why did Bodhidharma come from the West?

Whatever Bodhidharma’s reason, legend has it that he eventually settled in the Shaolin Temple in central China. Accounts differ as to what happened next. In the Japanese version of the story, he wandered into a mountain cave above the temple and sat in meditation for so long that he lost both legs. The Chinese, on the other hand, say that Bodhidharma foretold the dangers of excessive stillness long before any limbs had atrophied, and introduced a series of physical exercises based on Indian yoga. In this telling, the Shaolin Temple becomes the birthplace not only of Zen, but also of kung fu.

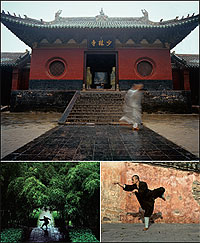

Justin Guariglia’s gorgeous new book of photographs takes us inside this legendary temple, known in the West primarily as the backdrop for Hong Kong action movies. Guariglia’s early shots convey the imposing physical structure of the temple as well as the tourist realm surrounding it. We see well-dressed pilgrims gazing through binoculars at Bodhidharma’s famous alpine abode, while discarded water bottles litter a nearby parking lot.

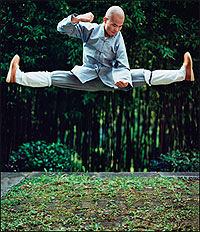

However, the “warrior monks” who live and train inside Shaolin are Guariglia’s true subjects. Still photography may seem a poor medium to portray the inherently fluid martial arts, but Guariglia’s genius lies in his ability to marry these unlikely partners perfectly. He creates several breathtaking stills, such as the striking image adorning the book’s cover of the monk Shi De Yang practicing a gravity-defying sequence called “big hong fist” [see above]. Elsewhere, the monks’ kicks and strikes dissolve into an eerie blur of unbridled motion. And perhaps the most striking images are the sequential shots of monks performing one of Shaolin’s myriad specialized forms. These pages achieve true transcendence, capturing both the perfection of each instant and the intricate continuity of the entire movement.

Guariglia’s book includes an informative essay by the writer and former Shaolin student Matthew Polly, providing useful cultural and historical background for the photographs. Polly’s contribution is in large part a reworking of material from his highly entertaining memoir American Shaolin, just released in paperback, an account of his martial arts studies at the temple in the early 1990s.

Polly seems to have encountered Shaolin at a unique moment in its fifteen-hundred-year history, when China’s early capitalist experiments briefly turned the monastery into what he calls “Kung Fu World, a low-rent version of an Epcot Center pavilion.” Polly’s view of the temple is much more human: rather than sacred warriors, the monks are the sorts of confused youths you might find on any American college campus. He gives the reader a fascinating sense of what it is like to train there for hours on end every day. Guariglia, meanwhile, picks up the thread at a point when much of the Disneyfied schlock had been cleared away, and in his book the temple comes across as a much more spiritual and otherworldly place.

Neither author offers much insight into the sitting practice Bodhidharma is said to have established at Shaolin. Guariglia has one nice shot of a monk in daily meditation. Polly eventually tries sitting meditation, too—as he puts it, “I didn’t just want to be a badass; I wanted to be an enlightened badass”—and he describes his attempt with the endearing self-deprecation that makes his book so enjoyable:

For the beginner, the reality is more like ten seconds of blankness, before random trains of thought start pulling into the station: my back aches… my friends are probably still in bed… no, it’s a fourteen-hour time difference, they are probably partying… this is the single dumbest decision of your entire life… I miss ice cream… I hope the Chiefs make it to the playoffs this year… no, I miss peanut butter more. Each of these trains of thought is quickly interrupted by self-recrimination: stop thinking… focus on your breathing… you lack discipline. And then the random thoughts start again.

As Polly’s book makes clear, Shaolin is no longer quite as shrouded in mystery as it once was. The bimonthly magazine Kung Fu Tai Chi now devotes an annual special issue to the temple and its distinctive forms of martial arts, and today anyone, from serious students to intrepid tourists, can arrange a tour with relative ease. Yet most of the world still knows the temple primarily through fictional accounts, and both these books offer a valuable glimpse into the real world of Shaolin.

DID BODHIDHARMA really live at Shaolin? The scholarly consensus appears to be that he did not. But there is still much to learn from this storied temple. Near the end of Polly’s stay, in a moment of despair, he asks the Shaolin monks for advice. What would the Buddha do if he were facing certain defeat in an upcoming tournament? Monk Xingming explains that Buddha “taught us the principle of universal love” and suggests that this could be the answer. But he is quick to add: “The Buddha had lousy kung fu.”