The Buddha may have had deep insight into the selflessness of all phenomena, but I sure do feel a lot like a self. Looking more closely, I can see at least five ways in particular that this sense of being a self is supported.

First, I feel as though I am the occupant of my body, the one who inhabits it. When I stand over here, I find myself at the center of the world I am constructing as various strands of sensory information are synthesized into coherent meaning. And when I walk across the room, that world-building apparatus seems to move right along with the body. I cannot help but view this body as the basis of the world I am constructing, and feel entirely and exclusively identified with it.

Second, I have a strong sense of being the beneficiary of the feeling tones that arise with every moment of experience, the one who experiences both pleasure and pain. When the feeling tone is pleasant, I am the enjoyer of that pleasure; when it is painful, I am the victim of that pain, the one to whom it happens. Nobody else suffers from this toothache, and only I have direct access to the joyful contentment I feel while admiring the beauty of this sunset.

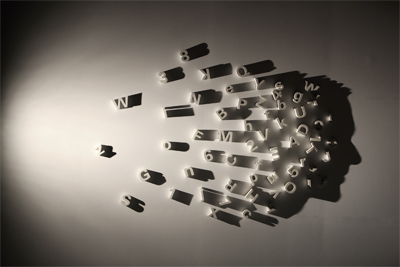

Third, I am the artiste, the person who expresses myself. John Lennon may be right when he says “There’s nothing you can sing that can’t be sung,” but I still feel that I am composing and enacting something special much of the time. However humble my creations, they feel like they come uniquely from me. Each of us has a creative narrator functioning within us, and as we put our hand (or pen, brush, musical instrument, etc.) to work, there is a tangible sense that we are expressing our selves.

Fourth, I also feel like an agent, the one who makes choices, who acts out those choices, and who experiences the consequences of those actions. Sometimes I do good, and sometimes I do harm, but either way I have the sense of being the person who is acting in the world and at the same time being the one who is responsible for those actions. When the outcome is favorable, I deserve the praise; when it is unfortunate, I am usually (though not always) willing to take the blame. Indeed, words like decision, action, and responsibility can only make sense when there is a person who makes the choice, does the deed, and inherits the consequences.

Fifth and finally, I cannot help having the view that I am some sort of essence, that I somehow consist of the awareness of all the above and more. The sheer “givenness” of consciousness, the bald fact that moments of awareness rise and fall in rapid succession in this particular stream of experience, provides the basis for a continuous sense of self. I am that upon which it all depends, around which it all congeals, the very heart of all that unfolds here and now as me.

Does all this self-making mean I am particularly dense and incapable of understanding the Buddha’s doctrine of nonself? Not at all. In fact, all these assumptions are natural and even to be expected. They are not, however, entirely as they appear.

The Buddha never said there is no self, only that the self is an illusion. When cataloguing the phenomenologically real aspects of experience discernible in meditation, the Buddha parses the apparent self into five aggregates or categories. Each of these serves as a basis for construing the self, for constructing the sense of there being a person who…, but each falls well short of actually qualifying as a self. The aggregates of material form, feeling, perception, formations, and consciousness serve as the basis for our taking on the view of being the person who is the occupant, the beneficiary, the artiste, the agent, and the essence, but in fact these functions are unfolding without belonging to, happening for the sake of, or in any other way constituting a self. Such a view of ourselves is very common, understandable, and even, perhaps, inevitable. But it is nevertheless merely a view.

Collectively these five assumptions add up to the mother of all views, the view of self as a really existing entity. In Pali, the word for this is sakkaya-ditthi, and when asked how it comes to arise, the Buddha answers, quite simply, that it arises when we regard the aggregates as “this is mine, this I am, this is my self ” (“Majjhima Nikaya,” 148). Self, in other words, is a projection of ownership onto all experience (this is mybody, these are my feelings, perceptions, formations, and this is my consciousness). The five aggregates really do occur—that is not in question. They just don’t belong to me. Experience occurs, but the person who owns it is a fictitious construction.

If the self is so simply created, it is just as simply abandoned. In the same text, the Buddha says that there is a practical way leading to the cessation of the view of self as a really existing entity: regard the aggregates as “this is not mine, this I am not, this is not my self.”

Why does such an apparently minor shift in perspective make such a huge difference? It turns out that so much of the harm we do to ourselves and others is triggered by this very sense of ownership and identification. If someone were to walk off with something I felt no attachment to, I would be entirely undisturbed. But if they took from me something I cherished, something I deeply felt belonged to me, it would immediately evoke greed, hatred, and a host of related unwholesome emotions and behaviors.

The self attitude causes suffering, the nonself attitude does not. It is as straightforward as that. This is the pivotal insight of the Buddha, and is meant to be investigated in your own—so to speak—experience.