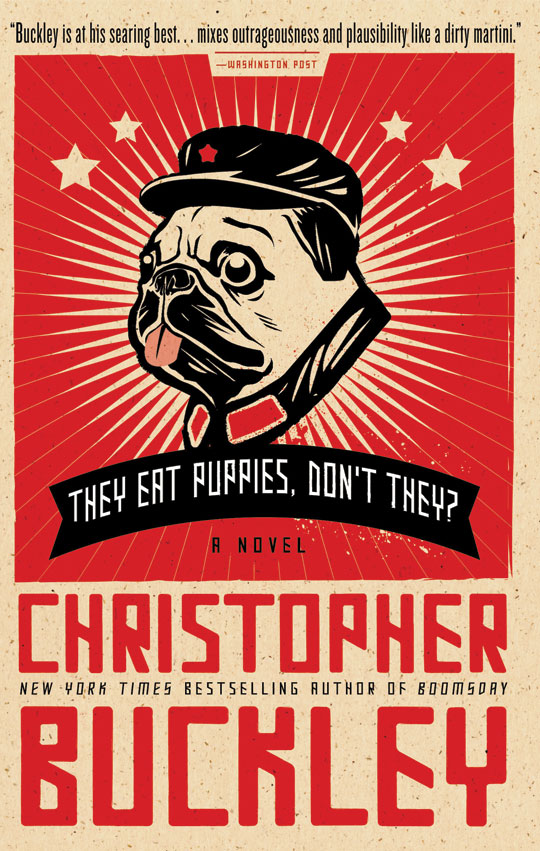

They Eat Puppies, Don’t They?

By Christopher Buckley

Grand Central, 2013

352 pp.; $15.00 paper

The giant military contractor Groepping-Sprunt has a problem. Their executives dream of building the ultimate 21st-century weapon: a “predator drone the size of a commercial airliner,” complete with Gatling guns, Hellfire missiles, and cluster bombs. But Congress is balking at the multi-billion-dollar price tag. A “breathtakingly large and lethal killing machine” like this—let alone the even more deadly materiel they have secretly planned—requires a similarly large and lethal enemy. And right now, it’s not clear that America has one.

But two unlikely saviors think they have the answer. Walter “Bird” McIntyre is a lobbyist for the fictional Groepping- Sprunt by day and a budding spy novelist by night. Angel Templeton is a right-wing political pundit at an equally fictitious think tank, the Institute for Continuing Conflict, who relishes her frequent appearances on cable TV news and named her 8-year-old son after Barry Goldwater. Together they unearth an enemy worthy of Groepping-Sprunt’s wondrous new weaponry: China.

Such is the premise of Christopher Buckley’s latest political satire, They Eat Puppies, Don’t They? The son of conservative scion William F. Buckley, he has previously skewered Big Tobacco, the Supreme Court, the Middle East, and American retirees. His 1994 novel, Thank You for Smoking, on the US tobacco industry, was adapted into the successful 2005 film comedy of the same name. In his newest effort—first published in 2012 and now issued in paperback—Buckley sets his sights on such varied targets as the military-industrial complex, American right-wing politics, Civil War reenactors, and, of course, the Middle Kingdom.

The story divides its time between Washington and Beijing. While the Washington half focuses on Angel and Bird, the Beijing chapters revolve around the recently appointed Chinese president, Fa Mengyao. Fa is facing down two disloyal lieutenants, the prickly ministers of defense and state security, while simultaneously suffering the combined indignities of insomnia and indigestion. Now he must also do what he can to avoid the very hostilities Bird and Angel are gallantly trying to provoke. Their would-be conflagration centers on the familiar flashpoint of Tibet and a possible plot to assassinate His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

Buckley’s novel follows the familiar conventions of a modern airport thriller: short chapters, quick cuts, an unlikely romance, and a sometimes bewildering array of characters. The 18 major “players” are helpfully listed before the first chapter, in case we get lost later on (which we probably will, and more than once). Buckley maintains a brisk pace, injecting more than enough suspense into his eminently readable prose to keep readers engaged throughout. His humor is broad but largely successful, and derives mostly from the fact that his conceit is somehow both patently absurd and yet entirely believable.

In fact, there often appears to be a trace of seriousness in Buckley’s very funny book. Sandwiched between the political shenanigans are some thoughtprovoking reflections on world affairs. Here, for example, is his refreshingly brutal thumbnail sketch of modern China:

The Communist Party controlled every aspect of life. It made Big Brother look like Beaver Cleaver. It was implacable, ruthless. The government lost no sleep driving tanks over students and Tibetan monks. It tortured and executed tens of thousands of “serious criminals” a year. It cozied up to and played patty-cake with some of the vilest regimes on earth—Zimbabwe, North Korea, Sudan, Iran, Venezuela; poured millions of tons of ozone-devouring chemicals into the atmosphere; guzzled oil by the billions of barrels, all while remaining serenely indifferent to world opinion.

These are substantive charges—albeit ones that some might make against the United States, as well. And yet, Buckley asks, “apart from a few forlorn Falun Gong protesters outside Chinese embassies or self-immolating Tibetan monks, where [is] the outrage?”

More specifically, Buckley repeats the troubling allegation that the Chinese government was involved in the 1989 death of the Panchen Lama. This “number- two lama, vice lama, backup lama” died of an apparent heart attack just days after he returned to Tibet and began making speeches mildly critical of the Chinese occupation. “So the Chinese have some street cred when it comes to offing lamas,” the defense lobbyist Bird sneers. But this isn’t exactly a joke.

For all these reasons, Buckley’s characters—and perhaps the author himself—seem genuinely surprised that China has not earned the sort of indignation once reserved for the Soviet Union. Like banks that are too big to fail, has China become too big to scorn? Buckley seems to think so. How can we stand up to the country if every one of us is “in hock up to his eyeballs” to the Chinese state?

Despite its comic pretensions, much of this material might hit a little close to home for some readers. Buddhists may have a hard time enjoying a story that treats the proposed murder of the Dalai Lama so lightly. Still, His Holiness is treated with more respect than most characters in the book, subjected to something more akin to gentle ribbing than to outright satire. “He’s a 75-year-old sweetie pie with glasses,” Angel explains at one point, “plus the sandals and the saffron robe and the hugging and the mandalas and the peace and harmony and the reincarnation and nirvana.” He is remembered even by the hard-boiled Bird as “a man who could laugh after everything he had been through—escaping assassinations, fleeing his native soil, watching it fall to invaders and occupiers—all the hardships, sorrows, and deprivations, yet still somehow ‘a fellow of infinite jest.’”

This reverence for His Holiness also illustrates the extent to which Buddhism in general, and Tibetan Buddhism in particular, have now fully entered the American mainstream. Familiarity with the Dalai Lama is assumed throughout the book. Oblique references to those mainstays of Hollywood Buddhism, Steven Segal and Richard Gere, appear without further elaboration. Everyone in America, it seems, is suddenly in on the Buddhist jokes. “Americans love the guy,” Buckley writes of the Dalai Lama. “The whole world loves him. What’s not to love?”

In the end, Buckley’s book serves to highlight a worrisome paradox in modern American politics. On the one hand, we continue to have a national obsession with finding (and perhaps fabricating) sinister forces against whom to organize. There seems to be a never-ending clamor for keeping “the armed forces well funded and engaged abroad, preferably in hand-to- hand combat,” a sizable contingent always looking for “the next calamity” and forcing America “into one tar pit of a quagmire after another.”

Yet on the other hand, even these “unapologetic advocates of American military muscle,” fixated as they are on finding new enemies, seem reluctant to consider the possibility that China’s size, ambition, and ambivalence toward human rights might make it the most plausible candidate. Instead, we seem to focus our endless rhetorical wrath on mere economic pipsqueaks, including such unlikely adversaries as Cuba and North Korea. Americans may love the Dalai Lama, Buckley seems to suggest, but perhaps they love cheap consumer products even more.

Even with such weighty themes lurking just beneath the surface, They Eat Puppies, Don’t They? remains a mostly lighthearted romp through today’s political landscape. Buckley even manages the neat trick of ending the sometimes macabre book on a largely positive note, with even cynical Bird getting a taste of enlightenment. As he reflects on the state of the world in the final pages, Bird exclaims: “It’s perfect as it is! Why do we always say ‘Oh, it could be better’? When it’s already perfect?”

Why, indeed. His Holiness couldn’t have said it better himself.