“History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake,” said Stephen Daedalus, James Joyce’s young alter ego in Ulysses. For anyone born in Ireland, enlightenment often begins with escaping the clutches of the past.

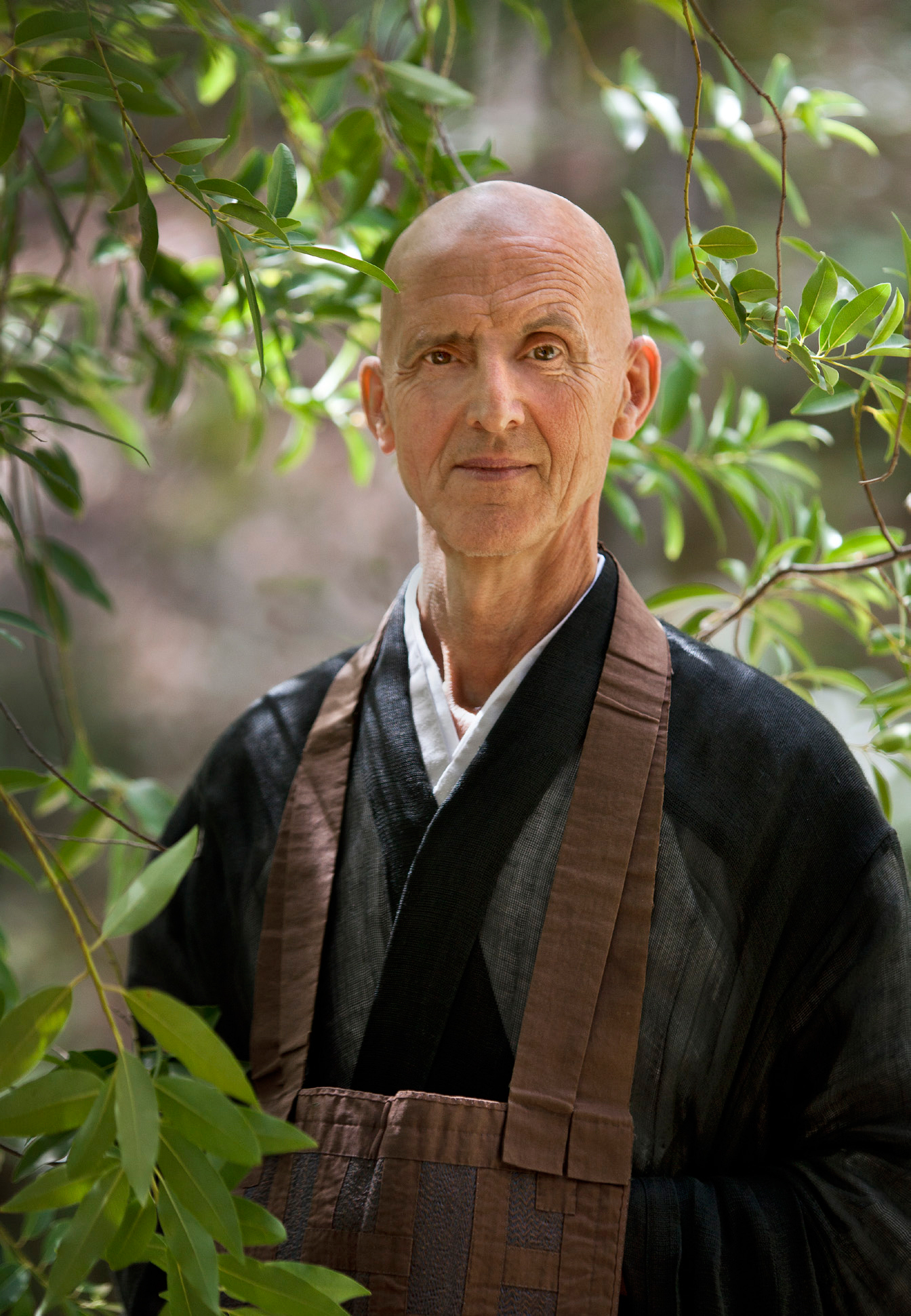

Ryushin Paul Haller, the former abbot of the San Francisco Zen Center, was born in Belfast. Like Joyce, he left Ireland when he was young, but he never became a complete exile. Twelve years ago Haller returned to Ireland and started a Zen center there, where he began to incorporate socially engaged Buddhism. He now returns to Belfast twice a year to teach at the center.

I came to know Haller’s teachings through his Saturday morning dharma talks in San Francisco, lectures punctuated by the mostly contemporary American poetry he quotes and the dry, almost cackling laughter that stops the clock anytime something strikes him as truly absurd. This March I spoke with Haller in the dining hall of San Francisco Zen Center, where he still serves as a senior dharma teacher.

Twelve years ago you returned to Northern Ireland, where you grew up, and founded a Zen center that incorporates socially engaged Buddhism and peace work. What form does working for peace take there? Northern Ireland is a unique place. It’s not very big. And it’s kind of homogeneous; it’s Catholic-Protestant, but they’re all white folks. There’s a strong sense of the whole community of Northern Ireland being in recovery—not in the AA sense, but recovering from 30 years of trauma and division. And because it’s small you can bring a deliberate attention and strategy to that in a way that’s not possible in a country the size of America. We work with community groups, of which there are a lot, coaching them on mindfulness.

The amazing thing is that mindfulness is now in the field of mental health; especially in the last five years, it has been accepted as a legitimate, effective modality. Part of the challenge is, how do you deliver it? You can give someone a bottle of Prozac and tell them to take one every day. You can’t deliver mindfulness in a bottle, tell them to take a mindfulness pill every day.

How do you deliver mindfulness in that environment? Britain and Northern Ireland have a strong social welfare system. It provides an infrastructure that can implement things within the community. When teaching mindfulness and stress reduction to community workers, I’m thinking: Here is a resource. I can work with these folks, teach them basic elements of mindfulness that they can bring out and deliver to the folks they have hands-on contact with. My notion is that if we engage these folks, tutor them, coach them, then they are going to turn around and offer a modified version of mindfulness teaching to the community.

Mindfulness as a technique is sort of value neutral; it’s taught in business, even the military. In an environment where you are trying to promote peace, is there a special spin you put on it? I’m looking at a society that’s in the aftermath of 30-plus years of sectarian strife. When 9/11 happened and the American population realized people could come here and bomb us, and there was all that fear and shock, I thought: Yeah, welcome to this harsh reality. I grew up in a place, as many people on this planet do, where you can be bombed on any day of the week. Throughout Northern Ireland any major locality was a target—from a retail store to a pub. And you could decide to stay home and never go out, or live in a world that was precarious and dangerous. When you have decades of that, you have an aftermath: the disintegration of a predictable, secure future. Kids become wild and lawless, people become embittered and entrenched in their politics and worldviews. So we try to provide a potent resource that can help to bring some mental, emotional, psychological, and interpersonal stabilization. It can facilitate some form of healing for that array of suffering. Hopefully it’s apolitical.

Why did you leave Ireland when you did? I looked at the community torn in half with religious bigotry, and the question was, “Are you with us or against us?” As far as I was concerned, that question was not one I wanted to have define who I was and who I was going to be.

Where did you go from there? I went to London, and then, as in many Irish stories, my mother died and it was kind of a radical shift for me. I was 22. I grew up in a lot of poverty but in a strong, passionate Irish family. When my mother died, the glue, the central person, was gone. It was like I now had permission to roam the globe. And that’s what I did. It was one of those existential moments when you say, Why am I doing this? And I didn’t have a good answer. When you grow up in poverty, one of your agendas is to get out of poverty. My motivation wasn’t political considerations; I was trying to lift myself and my family, particularly my mother, out of poverty. And then she died, and I said, Well, that’s not going to happen. So I just started to roam.

At what point would you say you began a spiritual quest? Almost as soon as I started to travel. I started off reading existentialism. I studied engineering. Let me tell you, engineers are not taught much philosophy, or anything except engineering, in my case.

After wending your way through Europe you ended up in the Middle East in the early 1970s. What was it like then? Wherever I ended up I found myself fascinated by how people constructed life—because I was very religious as a kid, so I was fascinated by religious beliefs. And amazingly, in those days you could wander around the Middle East. If you can imagine, I spent time in Syria and Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Jordan, and it was no big deal back then. You’d meet people and you’d talk and you’d go back home for dinner. But when I got to Buddhism, it was a love affair from day one. I ended up in Japan, and that’s where I got into Zen. I was 25.

Did you join a monastery in Japan? No. I went there to teach English. I’d just wander around and put something together wherever I ended up, just make it up as I went along. I’d marvel at these Americans who would call home and say, “Could you send me another thousand dollars?” [Laughs.] I discovered by coincidence I was living two blocks from a Zen Buddhist university and became a close friend of someone who was training to be a Zen monk. But even then the notion of a Westerner going to a Zen monastery was impossible. It wasn’t totally true, but that was the message I got: it just doesn’t happen. And then a friend said, “Why don’t you go to Thailand? They’ll take anyone there.” So I went to Thailand, and indeed they took anybody. And they put me in a solitary 10-day retreat, a little room twice the size of this sofa. And you’d just stay in the room.

Was that hard for you? Are you kidding me? [Laughs.] If I hadn’t been so earnest—I mean there was no way I was going to quit. Little room, thick walls, single light bulb hanging from the ceiling and absolutely no furniture, a grass mat to lie on. They’d bring your food; you’d go outside to go the toilet. And you’re there, and there’s the instruction: Just do this, 24/7. And to this day I couldn’t tell you if they just thought, Weird foreigner! Let’s put him in that room, he’ll leave in a few hours. But I came out of that room, out of that retreat, like, “Okay this is it. Sign me up!”

How did you end up in San Francisco? When I was in Thailand I met someone from San Francisco, and I was very impressed with him. He’d been here with Suzuki Roshi, and when Suzuki died he went to Thailand to be a monk. So I cut short my plan [to try different monasteries in the East] and came here.

You arrived in San Francisco in 1974. Did you join the Zen Center right away? Totally. I got off the plane and came here, knocked on the door, and said, “Hey.” And they said, “You can’t just turn up!” And in good Irish fashion I just looked at the guy and said, “Well, I just have.”

Ten years after you arrived, Richard Baker Roshi resigned from San Francisco Zen Center over allegations of sexual misconduct. How did the sangha work through that so that it wasn’t a distraction from what you were trying to do as a community? Well, it was an enormous distraction. There was a lot of secrecy; for many of us like myself who were sort of integral members, it was a shock: “I didn’t know that!” A good half of those core members just up and left. Folks who were peripheral were now turning up for everything, to express their indignation and condemnation. Which was more than a little dysfunctional. It was like, “Who are you? You came to a dharma talk last year, and now you’re here demanding we do what you say? Why would we do that?” At those things the loudest voice gets attention. We brought in a facilitator for the community, we set up a group process, we tried to look at what happened: Who are we now? How do we move forward? What do we need to address within ourselves, collectively, that will allow us to come to terms with the sense of betrayal? How do we feel about the veracity of Zen practice? We did a lot of group work. And it was consuming for two to three years. When people are hurting, that’s what they want to talk about.

There have been recent upheavals in the American Zen communities led by Sasaki Roshi and Eido Shimano, after both teachers were accused of sexual misconduct. How has your sangha responded? Both were significant in that they were happening for a long time. One of the big dilemmas is not being familiar with what’s exactly happening within the community, and also seeing something of the level of seriousness that is actually asking, or demanding, to be addressed. Because seeing nothing is to be complicit, in a passive way.

We at SFZC would never condone that behavior or support it, but being far removed from it, we haven’t needed to be proactive. Only yesterday, central abbot Steve Stucky wrote a piece in our weekly sangha news addressing sexual misconduct. And it says we do take it seriously and we have our mechanisms in place for people to come forward and say they were mistreated. That’s good for in-house, but how active should we be in criticizing or condemning Eido Shimano, who’s in New York, and we’ve heard the scuttlebutt for decades and decades? If you’d come to me personally and said, “Do you think I should practice with this guy?” I would have said, “Well, there’s something you need to know. I’ve heard it secondhand, but I’ve heard it often enough that there’s got to be some truth to it. It’s not someone I would recommend.” But am I writing letters to The New York Times, or following him around with a placard?

We struggle with that. Personally, I struggle with that.

Do you think your experience in Thailand had an effect on how you relate to communities outside of San Francisco Zen Center? When I was in Thailand almost 40 years ago, my experience of if was of an almost singularly Buddhist country. There were two primary Buddhist sects, but I wasn’t savvy enough to even know the differences between them, so that didn’t influence me much at all. In my own practice, I don’t separate Vipassana practice and Zen practice, I see a lot of commonality. I don’t hold either of those two kinds of Buddhism very separate, even though the way they manifest in the world is quite distinct and different.

I do see those communities, Zen and Vipassana, coming together. My hope for Buddhism in the West is that it will draw from the best of both those traditions—I don’t know enough about the Tibetan tradition to speak to that. I do see a lot of students, many of them very dedicated, who will do training in both. I’m doing this three-month retreat, and many of [the participants] are hoping to go off and do intensive Vipassana practice. I wouldn’t say I encourage my students to do both, but many of them, knowing my background, are inclined to do it, and when that inclination is there I encourage it.

There’s been a lot of community outreach—especially in hospice and jails—at San Francisco Zen Center since you became abbot. Was that something you were very keen on? That all snuck up on me. I was involved in the hospice pretty soon after we started that program, and I’m still on the hospice board—I’ve been involved all these years. Before I was abbot I was in charge of outreach, and a lot of these programs I dreamed up. Who can say why we do anything? But I think it had to do with the background I came from. I came from a tough part of town, a lot of poverty; I was a second-class citizen—those things make their mark on you. And either they embitter you and diminish you, or they set you on some odd notion that you can offer some benefit and temporarily alleviate them. And I got caught in the latter.