In 1959 a young Ch’an monk named Tsung Tsai escapes the Red Army troops who destmy his monastery and flees from the edge of the Gobi Desert to Hong Kong Hunted, starving, and knowing that his fellow monks are dead, Tsung Tsai is borne up by his mission: to canyon the teachings of his elderly master, who remained in his mountain to cave high above the monastery.

Almost thirty years later, during a snowstorm outside Woodstock, New York, Tsung Tsai meets up with his irreverent American neighbor, a libertine poet named George Crane. In the first part of Bones of the Master, Crane mixes his own witty and lyrical prose with Tsung Tsai’s wondelfully eccentric rendition of English to retell the monk’s escape from Communist China. Subsequently, Tsung Tsai persuades Crane to accompany him on a return pilgrimage to Inner Mongolia to find his teacher’s bones and to provide a proper burial for his master. Much of this book is Crane’s exquisite account of their impossible journey together—a pure-hearted monk on a mission and a wild poet seeking freedom, adventure, and sensation. In this excerpt, Tsung Tsai and Crane are visiting the monk’s great niece, who lives in Tsung Tsai’s natal village, where many of his kin were slaughtered or starved by the Red Army.

I took my second jar of tea out of Fang-fang’s yard. The early morning sun was white without warmth. Tsung Tsai’s face was gray, and he was sitting on the stoop, busy, as always, sewing a split seam in the rump of his cinnamon-colored coolie pants. The pants and his matching collarless jacket were heavily patched and held together, as usual, with a network of safety pins. The pants were cut short, their cuffs lashed around his shins with yellow silk braid. The braid was his one concession to finery. His socks came up under his cuffs, and the braid was supposed to keep them from slipping, but no matter how he lashed and tied them, one sock or the other would inevitably sag. He looked like a hermit monk, a ragged eccentric. But when he wore his robes he was transformed, a Buddhist master once again, elegant and austere, physician and sage, mediator between the living and the dead.

This morning he wore a black NorthFace polar fleece vest, the only item left from the gear bought before we departed for China. The Patagonia parka, Technic hikmg boots, polypropylene underwear, and wicking socks—which I had bought him so that he would be equipped and warm on what promised to be an arduous journey for a seventy-year-old man—he had given away in Mouth of West Mountain soon after we arrived. I had come out of the bathroom of Linn’s loft one morning to see an old woman departing with his parka tucked under her arm. Soon he was left with nothing but his rags. He had given away the wristwatch, the fanny pack, his ski gloves, and the camera that he had insisted he needed. He had kept the fleece vest, he said, because it was “good for meditation.” I drew the line when he tried to give away my equipment, offering an old farmer my camera.

The mending needle danced in his hand. Its curved point dove through the thin fabric, disappeared, and then resurfaced in a quick, steady tempo. He contemplated the patchwork of his garments. “Georgie, my culture is completely Confucius and Taoism mixed with Buddha. Very humble.”

“I met Confucius once,” I said.

“True?”

“In Marrakech. Morocco.”

“Africa,” he nodded.

“It was 1971”

I didn’t tell him I was recovering from an accident in the western Sahara and had been pissing blood for a couple of weeks and self-medicating, constantly stoned on a mixture of hashish and opium. It was just after sunrise. I sat on the veranda of the Hotel Tangiers, wrapped in a Berber djellaba, sipping sugary mint tea. The square below was filling—camel traders, jugglers, fortune-tellers, beggars, and scribes.

“I saw him in a dream.”

“Confucius?”

“I was meditating”

“Meditation?”

“He spoke to me.”

“Confucius talk to Georgie? Strange.”

“Yes, very. He said to me, ‘Of birds I know that they have wings to fly with, of fish that they have fins to swim with, of wild beasts that they have feet to run with. For feet there are traps; for fins, nets; for wings, arrows. But who knows how dragons surmount wind and cloud into heaven ‘”

Tsung Tsai cocked his head to the side and closed one eye. Then he laughed. “So good Georgie story,” he said.

“You’re my dragon.”

“This you say true.”

I went inside, poured him another jar of hot water from the thermos, and returned.

“Georgie,” he said, staring into the dirt at his feet. “My teacher’s cave very far. Very very long. If I return alive, I am very happy. “

“Tsung Tsai, maybe we shouldn’t make the climb.”

“I don’t care what you do. Go. Don’t go. Doesn’t matter. I go. No choice. I have purpose. I have duty. Easy. Hard. Doesn’t matter. I go to my teacher’s cave. And I am talking east, west, north, south. But you know, I am older. Seventy-one. I look strong like tree. But you never know. You never know when tree will fall.”

“I’m just worried about you,” I said. “If you go, I go”

“Don’t worry. I tell you again and again. I never stop. Never. Long life is not important. Even you live to two hundred. Three hundred. Even a long life is a short life.”

Bones of The Master will be published in March 2000 by Bantam Books.

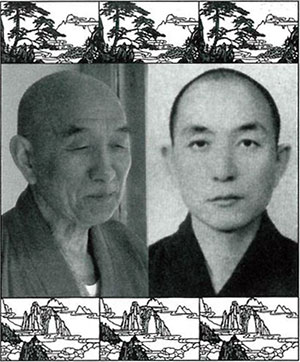

Tsung Tsau and George Crane speak with Tricycle

George, have your habits changed as a result of your friendship with Tsung Tsai?

GC: Life was pretty wild when I met him [chuckles].

TT: Excuse me. She asked you how after you met me you change your habits!

GC: I became legal I got my driver’s license, I paid my taxes.

TT: More! More please! You pay your family debt, your friend debt, you neighbor debt. Now only keep one wife, no more keep girlfriend. No more eat bad food. Now almost vegetable!

What did you each hope to get across with Bones of the Master?

TT: So special book. Georgie do very good Job, put lots of energy into this book. You begin to understand Chinese mind, Chinese culture. And then you understand Buddha mind. Chinese mind is very close to Buddhist mind.

GC: More than anything, I wanted people to get to know Tsung Tsai. Second, I wanted to portray his kind of Ch’an, a very pure Buddhist expression. It’s generous, it’s earthy, it’s undoctrinaire. And I wanted to show our relationship, which is not strictly teacher-student—though it is that—but it’s also a friendship. This is a buddy book, and I think that perspective opens up a different way of looking at a Zen master.

Rev. Tsung Tsai, do you see a future for the monk’s way in the West?

TT: Monk, no monk, doesn’t matter. People need to learn compassion, first for self, then neighbor, then country. Someday, when American people know more about Buddha, maybe many become monk. Many girl become bhikshuni. Because Buddhism so kindness! So freedom! So special! Always say the truth. It’s just natural. Everyone needs Buddha mind.

—Mary Talbot