The Buddha wasn’t always seen as a figure of peace and compassion. Centuries before Buddhism became mainstream in the West, colonial explorers, missionaries, soldiers, and scholars who visited the East described the worship of a diabolical figure, a pagan idol. As Jesuit priest Guy Tachard (1651–1712) said of the Buddha he encountered in Thailand (then Siam), for example: “All these Idols are represented by fantastic and monstrous Figures. One of them is form’d like a Giant, and by them called Buddu, who formerly liv’d a very holy and penitent Life.”

In Strange Tales of an Oriental Idol: An Anthology of Early European Portrayals of the Buddha (University of Chicago Press, December 2016; $27.50, 257 pp., paper), Donald S. Lopez Jr., the prolific scholar and teacher in Buddhist and Tibetan studies (he is also a Tricycle contributing editor), presents translations of letters and texts from such travelers as Marco Polo, Voltaire, and St. Francis Xavier, among others, unveiling the efforts of Europeans over the course of 1,500 years to describe and understand an unfamiliar religion.

Lopez notes that Europeans regarded the Buddha with suspicion for centuries. It wasn’t until 1844 that French scholar and Orientalist Eugène Burnouf described the Buddha in Introduction à l’histoire du Buddhisme indien as a compassionate founder of a religion—and a human being. This image has held sway in the Western imagination ever since.

Strange Tales is an impressive contribution to Western intellectual history that will be relished by scholars across disciplines and readers curious about how stories evolve when passed through the lens of time and culture.

In 1849, the Scottish essayist and historian Thomas Carlyle first described economics as the “dismal science,” based on a prediction that the growth rate of the human population would forever outpace our ability to grow enough food for all. Today, a century and a half later, the effects of unregulated free-market capitalism, including the destruction of the environment and staggering societal inequality, has lent credence to this bleak vision. And yet a handful of contemporary thinkers have begun to develop new economic models that have the potential to change the reductionist nature of economics as it’s taught today.

In Buddhist Economics: An Enlightened Approach to the Dismal Science (Bloomsbury Press, Feburary 2017; $25.00, 224 pp., cloth), Clair Brown, a professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, asks, “What would a Buddhist approach to economics, in which people are regarded as more important than output and a meaningful life is prized above a lavish lifestyle, look like?”

Brown envisions an economics built upon social equality, an attention to interdependence, and overall sustainability. With these concerns at the heart of her model, she addresses two of the biggest threats facing humanity today—global warming and income inequality—and shows how a Buddhist system of economic valuation can address them more effectively. Her ideas are laid out clearly and concisely; noneconomists among us will have no trouble understanding her view.

Brown’s book articulates a vision for the future, but for a brief history of how we got to where we are, try independent economist Joel Magnuson’s From Greed to WellBeing: A Buddhist Approach to Resolving Our Economic and Financial Crises (Policy Press, November 2016; $24.00, 272 pp. paper). In reviewing the history of modern economics, Magnuson offers a Buddhist critique of the value system it relies upon, arguing that modern economics is fueled by the Buddha’s “three fires” of greed, aggression, and delusion. These poisons he says, are embedded within our financial institutions and are responsible for our attachment to “growth” as the only measurement of economic success.

Like Brown’s book, Magnuson’s owes a debt to the renowned economist and author of Small Is Beautiful (1974), E. F. Schumacher, one of the first to propose an economic system that values human liberation over material goods. He also coined the term “Buddhist economics.” These two titles take a creative approach to understanding our world and will motivate and inspire you as a Buddhist, citizen, and human being. Read together, they prove that the discipline of economics need not be dismal after all.

Ministers in the Christian traditions have a glut of resources that help them provide pastoral care to their congregations and communities, but far fewer—if any—guidebooks exist for Buddhist leaders in the West. Nathan Jishin Michon, a Ph.D. student at the Graduate Theological Union and an interfaith minister practicing in the Thai Forest and Shingon traditions, and Daniel Clarkson Fisher, a documentary filmmaker and writer who served as the first chair of the Master of Divinity in Buddhist Chaplaincy program at University of the West, sought to address the lack by compiling the guidebook A Thousand Hands: A Guidebook to Caring for Your Buddhist Community (The Sumeru Press, November 2016; $34.95, 386 pp., paper).

Voices from across traditions weigh in on topics under three major categories: “Working with Ourselves,” “Working with Others,” and “Working with Communities.” The first section covers, among other topics, “Listening as Spiritual Care” and “Nonviolent Communication”; the second includes chapters on cancer, depression, addiction, and domestic violence; and the third examines social systems and constructs such as race, gender, poverty, and accessibility.

This guidebook will be a useful resource for Buddhist teachers and counselors, and would make a good addition to a sangha’s library of reference works.

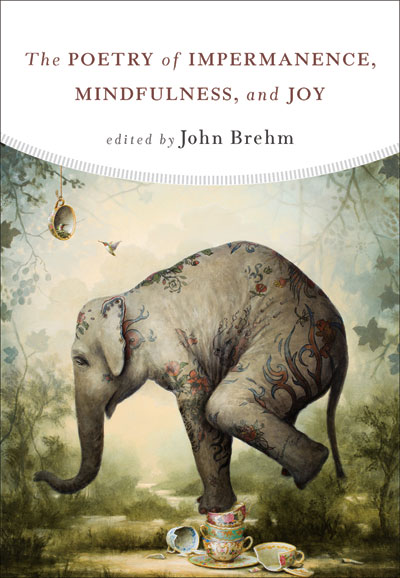

The Poetry of Impermanence, Mindfulness, and Joy (Wisdom Publications, June 2017; $16.95, 312 pp., paper) explores these three Buddhist themes in the poetry of writers both Buddhist and non-Buddhist. As the book’s editor, the poet and teacher John Brehm, says in his introduction, the anthology rests on the underlying premise that mindfulness of impermanence leads to joy—a phenomenon that poets around the world have written much about. By selecting work from non-Buddhist writers who most strongly express these themes in their work, like Pablo Neruda, Wislawa Szymborska, Tracy K. Smith, and Elizabeth Bishop, and setting them against well-known contemporary and ancient Buddhist writers such as Gary Snyder, Jane Hirshfield, Li Po, and Basho, Brehm shows that the three Buddhist topics of the title are rooted in a universal and deeply felt human experience. (And who better than poets, whose role is to notice and convey what goes unarticulated by others, to express this?)

The book also includes a helpful appendix of two short essays that can guide readers in a basic approach to reading poetry: “Mindful Reading” and “Meditation on Sounds.” At the book’s close, Brehm includes short biographies of each poet. While this collection would make a lovely gift for a poetry-loving or dharma-practicing friend, it could also serve as a wonderful gateway to either topic for the uninitiated.

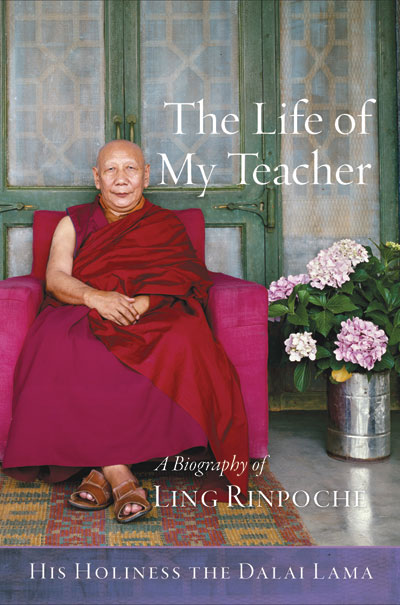

The Sixth Ling Rinpoche, Thupten Lungtok Namgyal Trinle (1903–83), was one of the great Tibetan Buddhist teachers of the 20th century and the senior tutor of the current Dalai Lama, for whose ordination and philosophical training he was responsible. Following a long-standing tradition of disciples writing about the lives of their spiritual teachers, The Dalai Lama himself has written this hagiography in the Tibetan religious style. The Life of My Teacher: A Biography of Ling Rinpoche (Wisdom Publications, July 2017; $29.95, 472 pp., cloth) is the only biographical work the Dalai Lama has penned.

The book covers Ling Rinpoche’s life from childhood through his later years, his exile in India, and visits to Europe and North America, and provides an in-depth look at how the relationship between a teacher and his students is developed and strengthened. It also provides records of the formal teachings Ling Rinpoche gave and received during his lifetime.

Although the traditional style may be dry for modern Western readers, the list of teachings—formerly available only to Tibetan speakers—will be of great value to the English-speaking Buddhist community.