This three-year-long exhibition, part of a rehanging of the Smithsonian’s Freer and Sackler galleries’ permanent collection, shows what magic can be worked with a clear objective and access to some of the world’s most beautiful Buddhist art. Comprising some 250 objects, all drawn from the Freer/Sackler’s holdings, the show grew out of a 2013 meeting among scholars, curators, designers, and representatives of the lead sponsor of the exhibition, the Robert H. N. Ho foundation, a Hong Kong–based organization dedicated to promoting a deeper public understanding of Buddhism and Chinese culture.

As cocurated by Debra Diamond, the Freer/Sackler’s curator of South and Southeast Asian art; Robert DeCaroli, an art historian specializing in the early history of Buddhism; and Freer Fellow Rebecca Bloom, the exhibition presents an overview of Buddhist thought that spans two millennia and the three major schools of Buddhism—Nikaya, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. When a museum holding a premier collection of Asian art turns its attention to a show about Buddhism, the results are bound to be engaging; but what truly sets this exhibition apart is its emphasis on the original purposes and meanings of the objects on view. Rather than organize the artworks by style, region, or period, as is usual in museum displays, Diamond and her collaborators have created thematic groupings of objects, accompanied by lively wall texts and labels, that lay out Buddhism’s core principles; interactive kiosks for the curious that provide more specific information about individual pieces; and several immersive environments that bring the rituals behind the objects to vivid life.

nikaya

(lit, “collection, group”), may refer to early Buddhist texts; it is also the term now used by scholars to refer to the early Buddhist schools.

This is an exhibition with a difference, presenting through art the myriad ways Buddhism may be practiced, from solitary meditation to communal celebrations, and the myriad forms its iconography can take, from immense stupas to tiny clay images carried by pilgrims. “We wanted to create contexts by which people could understand the objects as something more than artworks,” Diamond told me last spring. “Why were they made? How did Buddhists engage with them? And what does it mean for them to now be in a museum? So we created this exhibition about art and practice.”

The show opens with images of the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, who more than 2,500 years ago renounced a princely life to seek an answer to the pain of existence. After his death, his teachings spread across Asia and are common to all forms of Buddhism.

Four stylistically different Buddha heads greet visitors at the door—including a delicate 2nd- or 3rd-century Indian portrait in red sandstone from the northern Indian city of Mathura, as minimal as a Matisse drawing, and a more folkish 18th-century bronze from Thailand; nevertheless, each one incorporates many of the signs and marks that traditionally identify the historical Buddha, such as long earlobes, a cranial bump, and a dot between the eyes. A touchscreen kiosk allows visitors to pose more questions about the display, including asking the sculpture how it got there—the answer to which touches on looting and the often illegal ways whereby such objects end up mutilated and in museums.

From here, the show moves on to the idea of multiple buddhas, which all schools believe in, though the Nikaya schools believe that only one Buddha is living at any particular time. In contrast, Mahayana Buddhism, a later outgrowth, believes that multiple buddhas can exist in the world simultaneously. A small bronze altarpiece, commissioned in 609 by a daughter for her father and mother, vividly articulates this new idea, depicting a scene from the Lotus Sutra in which the Buddha of the Past comes to hear the historical Buddha at the moment he begins to teach.

One of the tenets of Mahayana Buddhism is that all sentient beings have the potential to become buddhas. As the number of buddhas grew under Mahayana’s influence, so did the number of specific practices devoted to them. The Buddha Amitabha, for instance, depicted here as a wasp-waisted, muscular youth in a patched robe, took a vow to create a Pure Land, into which those who call on him can be reborn and there become buddhas themselves. An exuberant Chinese stone stele, carved with a pattern of 1,000 buddhas, commemorates the Buddha Maitreya, the Future Buddha, who waits, pensive, for the next age to arrive.

Two immersive environments bring the practice of Buddhism into the immediate present. A vitrine of small objects shaped like stupas—structures built to contain Buddhist relics—is a lead-in to a hypnotic three-channel video showing a single day, from dawn to dusk, at the Ruwanwelisaya stupa in Sri Lanka. Shot this year, the footage shows groups of Sinhalese Buddhists making communal offerings of bolts of cloth—which are wrapped around the structure before being donated to the monks for new robes—as well as gifts of flowers, light, incense, and prayers. The movie ends with an extraordinary shot of the stupa glittering with thousands of butter lamps in the encroaching darkness.

A second immersive environment is an approximation of the kind of traditional Buddhist shrine that would have belonged to an aristocratic Tibetan family [see p. 89]. Created from a gift of 243 pieces of Tibetan sacred art by the collector Alice S. Kandell, the shrine—with help from Tibetan lamas and Western scholars—has been arranged as it would have appeared in an important lama’s home, with sculptures arranged hierarchically on stands and flanked by thangkas [scroll paintings].

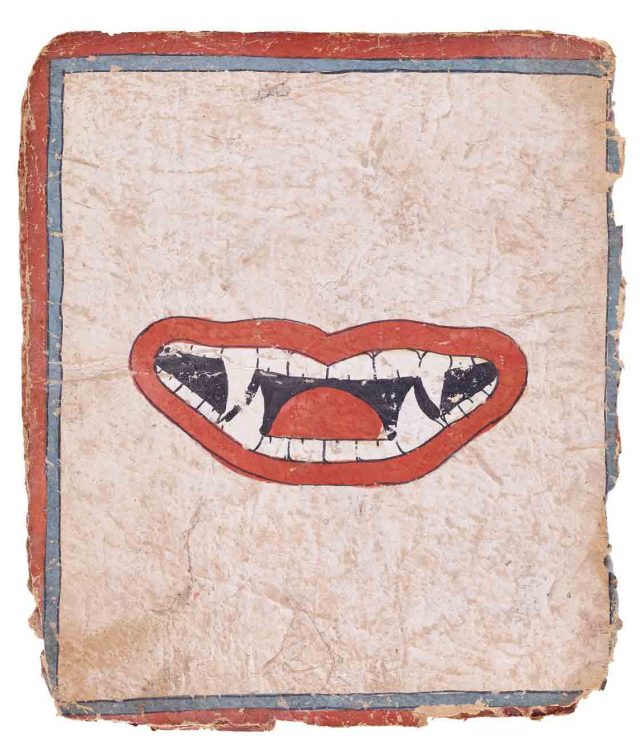

Pride of place just outside the shrine goes to an 18th-century copper sculpture of Padmasambhava, the semilegendary master venerated for bringing Vajrayana teachings from India to Tibet in the 700s, as well as for converting demons (i.e., gods of other religions) into protectors of Buddhism. Some of the most engaging exhibits in the show are vitrines containing images of these enlisted guardians, including one containing a sculptural depiction of a saucy, plump-rumped, and beribboned Jambhala (originally the Hindu god Kubera), who grants riches and wishes, accompanied by his gem-spitting mongoose.

Bodhisattvas—future buddhas who have chosen to stay in the world to help other beings—are also given their day, with extra attention paid to their polymorphous guises. And although buddhas were generally depicted in monk’s robes while bodhisattvas were shown in luxurious clothing and jewels, one modest 7th-century tin figure of a bodhisattva, part of a hoard of such figures discovered in Thailand, has the matted hair and simple loincloth of an ascetic—perhaps the form in which he could do the most good.

Near the end of the show, a map depicts the scope of the Buddhist world, from Afghanistan to Japan and from Mongolia to Indonesia, while yet another kiosk traces the journeys of Hyecho, a young 8th-century Korean monk who set out to see the birthplace of Buddhism in India and eventually traveled as far as Iran. The Silk Road brought pilgrims like Hyecho, along with monks, migrants, and merchants, to such remote sites as Kizil, an oasis town in northwestern China. Fragments of brightly pigmented 6th-century Buddhist paintings from the walls of the caves at Kizil testify to the cosmopolitan makeup of its visitors by showing personages, of different colors and wearing a variety of costumes, all listening to the words of the Buddha.

The final room in the exhibition is modest in the extreme, containing little more than an 8th- or 9th-century Indianstyle Javanese Medicine Buddha and a 13th-century Cambodian statue of Prajnaparamita, who embodies the perfection of wisdom. The little Buddha’s back is inscribed with a mantra, or sacred passage; a film nearby translates its meaning for visitors. At a time when the world desperately needs both healing and wisdom, these small, clear-cut figures make a fitting conclusion to the show.

But they also might make an intriguing beginning—visitors are free to take in this exhibition following their own path and at their own pace. Its quiet exhibits, organized concentrically, can be navigated in any order while still making sense, and will change over time in response to feedback from visitors. (My own wish would be for a slightly less moody design—while soothing, the dark maroon walls also reminded me of Robert Wright’s caution in the New York Times of November 6 not to make Buddhism too exotic.) If you are at all interested in Buddhism, try to make it to Washington to see this show. You’ve got three years.