Last May, former Marine Daniel Goolsby, 61, lost his job and fell into a deep depression. His savings gone, he was three months behind on his rent—and fed up with psychiatrists who wanted to “fix” his depression with heavy medication. Goolsby dragged himself, a downtrodden man, to St. Patrick Center in St. Louis, Missouri, hoping that its staff could help him find a job and turn his luck around. He never dreamed that within just a few months, an innovative combination of art, theater, and Buddhism would completely transform his life.

Last May, former Marine Daniel Goolsby, 61, lost his job and fell into a deep depression. His savings gone, he was three months behind on his rent—and fed up with psychiatrists who wanted to “fix” his depression with heavy medication. Goolsby dragged himself, a downtrodden man, to St. Patrick Center in St. Louis, Missouri, hoping that its staff could help him find a job and turn his luck around. He never dreamed that within just a few months, an innovative combination of art, theater, and Buddhism would completely transform his life.

The center, which provides services for the homeless and those at risk of becoming homeless, assigned Goolsby a case manager, Emily Piro. Last September, Piro, a counselor with a background in the performing arts, approached Goolsby with a proposition: would he like to take part in a project called Staging Reflections of the Buddha? The project would pay Goolsby and 15 others—all homeless vets or ex-prisoners—a small stipend to interact with an exhibition of Buddhist art in the Pulitzer Foundation’s gallery. After spending time with each piece and tape-recording their reactions, they would participate in theater exercises, learn about Buddhist philosophy, and eventually perform a theater piece that told their personal stories while also educating gallery visitors about the art and its history.

Goolsby said no. He wanted to spend his time looking for a part-time job, not learning how to meditate and write haiku.

“Give it three weeks,” Piro said. “If you don’t like it after three weeks, you can drop out.”

Six months later, the cast of Staging Reflections of the Buddha had given 15 sold-out performances, ending their three-week run in early March with a lantern lighting ceremony. And Goolsby? “I’m hooked on the meditation,” he admitted. “It is turning my life around.”

Staging Reflections of the Buddha is the brainchild of Lisa Harper Chang, director of the Pulitzer Foundation’s community projects, and Matthias Waschek, its former director. In 2009, they came up with the idea to combine theater, visual art, and social work. For the first project, Staging Old Masters, the performers worked with 13th- and 14th-century paintings depicting the Old Testament.

As in Old Masters, the performers in Reflections of the Buddha led an audience through the Pulitzer Foundation gallery, explaining each piece of art through their own initial reactions to it. But unlike the prep for the Old Masters project, the process of developingReflections of the Buddha focused on learning not only about the art but also about the religious tradition behind it. Buddhist monks and laypeople came in to teach the performers about Buddhism and lead workshops on various meditation techniques.

As in Old Masters, the performers in Reflections of the Buddha led an audience through the Pulitzer Foundation gallery, explaining each piece of art through their own initial reactions to it. But unlike the prep for the Old Masters project, the process of developingReflections of the Buddha focused on learning not only about the art but also about the religious tradition behind it. Buddhist monks and laypeople came in to teach the performers about Buddhism and lead workshops on various meditation techniques.

The exhibit featured primarily works from the 2nd to 8th centuries—bronze deity statues, Tibetan thangkas, sculptures of Ananda and Amitabha Buddha. There were also three contemporary pieces, including Blue Black by Ellsworth Kelly, an almost 30-foot-high aluminum panel with the top half painted blue and the bottom half black.

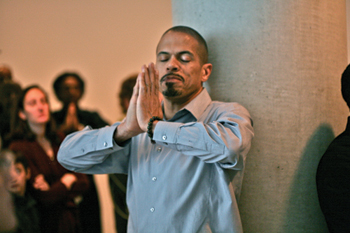

During the show, Goolsby stood in front of Blue Black with four other performers, exchanging banter about the Buddha’s long earlobes in the 6th-century marble statue near them. The scene ended with Goolsby’s reflection: “As a kid I would lay down and look up toward the sky, and where the sky and the top of the trees met, I felt they were complementing each other right there, and there was power being cast from where they met. I was absorbing that power. That gave me strength to carry on.”

At its heart, Staging Reflections of the Buddha is about empowerment. The hope is that the theater techniques and Buddhist philosophy the performers learned during the five-month development phase will aid them in their search for housing and employment, as well as help them to handle their lives and emotions with greater ease.

The stipend for the performers was provided by the Pulitzer Foundation, the St. Patrick Center, and the program Prison Performing Arts, whose artistic director, Agnes Wilcox, directed and wrote Reflections of the Buddha. The money is meant to encourage participants to view their work in the program as a job that expects them to be punctual and accountable.

But unlike many jobs, performing in Reflections of the Buddha seems to be life-changing. “The actors find it to be a transformative experience,” said Lisa Chang. “For a lot of them, this is the first time they have ever been paid to think. Usually they have had manual labor jobs, if they’ve had jobs before. So for them to come into a space, a very precious space like a museum gallery, and for us to tell them, ‘We want to pay you just to tell us what you think about the art and then to share that with other people,’ it’s profound.”

The benefits of the program are written all over the performers’ faces. “People who don’t normally smile, as soon as you ask them how the performance went, they grin,” said Piro, who served as lead case manager for the project.

“Yeah, she’s probably getting tired of seeing this smile,” said Goolsby, who now meditates up to three times a day and is studying the Lotus Sutra in his spare time. “I told her the other day, you can go ahead and say I told you so. It’s okay. I ain’t mad at you.”