Everyone’s trippin’ over the recently reignited psychedelics and practice debate (“Psychedelics’ Buddhist Revival,” by Gabriel Lefferts, tricycle.org, July 27, 2018). Rik Jespersen took the middle way, writing that psychedelics can “be helpful mental health tools . . . but there’s no getting around doing the work of meditation practice.” Longtime practitioner “Mike” cited his own positive experience with ayahuasca and asked, “Why aren’t the native cultures and ways of healing given the respect they deserve?” Reader Payt Kritz commented: “Anti-psychedelic Buddhists are basing their perception of psychedelics not on Buddhist ethics but on the norms of Western culture.” But Zen monk and author Brad Warner called the piece “free advertising for mind-altering drugs” and penned his own response in “It’s the Journey, Not the Trip” (tricycle.org, September 7, 2018). Many readers agreed with Warner’s position: @SkraelingMike tweeted, “[Warner’s] point about the dangers of dangling the shortcut [of psychedelic drugs] in front of struggling addicts should be End of Discussion in Buddhist communities.” Yale University’s Coordinator of Buddhist Life, Sumi Loundon Kim, agreed, adding that she is “grateful for Brad’s courage to speak up and take a stand.” Chou Wen Li summed it up: “Buddha gave five precepts. Sobriety is one of them. It’s not complicated.”

To bring historical context to the investigation into sexual abuse at Shambhala International, we republished a groundbreaking 1990 exposé on the organization’s first two leaders, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche and Ösel Tendzin, by veteran journalist and Tricycle contributing editor Katy Butler. “Encountering the Shadow in Buddhist America” (tricycle.org, August 1, 2018) was first published in the now-defunct journal Common Boundary. In “Same Old Story in a New World” (tricycle.org, August 1, 2018), Tricycle’s executive editor, Emma Varvaloucas, interviewed Butler about what’s changed (and what hasn’t) in the 28 years since the article’s publication. Many readers saw connections between past abuse cases and those brought to light in the #MeToo era. Lee Carlson remarked on “continued denial and enabling . . . The same patterns of behavior are repeated, albeit with new abusers and victims.” Carlson concluded, “It appears that the very institution of Shambhala International has an endemic disease harking back to its founding. Perhaps it is time to close it down.” Michael Roe gave thanks for “a story of courage . . . a first salvo in what has become a strong awareness now about sexual abuse in so-called Buddhist communities.” Others expressed concerns: reader “Dave” asked whether the piece was part of a “nontolerant political movement” that “sees men, and especially white men, as an oppressive enemy.”

In “Samaya and the World of Shambhala” (tricycle.org, August 6, 2018), Dan Montgomery, a former student of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s, explained why samaya—widely thought of in Vajrayana as a vow to follow the instructions of one’s teacher—should be understood instead as a commitment to one’s own experience of awakening. He did so in light of newfound criticism of the Shambhala founder’s womanizing, drinking, and drug use. Author Nancy Steinbeck remarked, “Brilliant analysis, Dan. Thank you for your clarity, especially in terms of the historical facts.” Nancy Rose Walker commented, “The minute a teacher steps out of their vows and sexually harasses, they are in the wrong.” Ken McLeod further explained why samaya vows are not a commitment to do “whatever your teachers says” in “How Samaya Works” (Fall 2018), prompting reader “Frit” to consider “how the Tibetan traditions of lineage, empowerment, and devotion can be maintained in the 21st century. McLeod knows what he’s talking about, and this article points a way forward. I hope it receives the attention it deserves among both Western students and the Tibetan diaspora.”

“A Call to Conscience” (Fall 2018), Ven. Bhikkhu Bodhi’s appeal for a collective Buddhist voice to emerge in the public sphere, found its audience. “Let us get to work,” wrote Brian Victoria. But Casey Hayden, a founding member of Students for a Democratic Society, issued a warning: “I suggest we recognize that our path is for everyone, of all political persuasions, not just those with whom we agree. As Buddhists, we do not have enemies. Beware of solidarity if it asks us to make them. . . . Because we understand that all views arise from causes and conditions, we should look deeply at the causes of problems beyond the analyses of single-issue interest groups.”

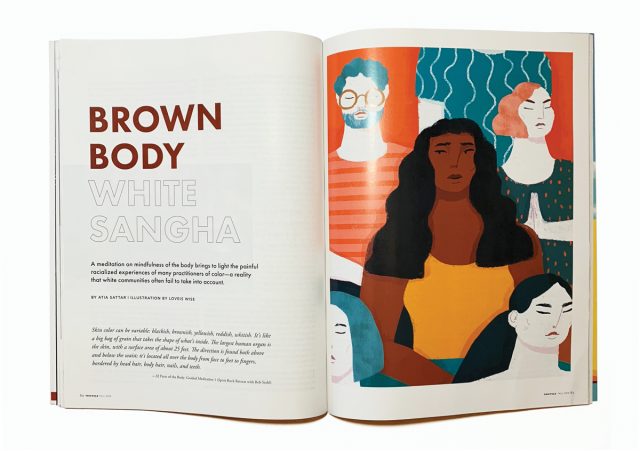

Atia Sattar’s account of her painful racialized experiences in predominantly white communities, “Brown Body, White Sangha” (Fall 2018), ignited a passionate discussion. The Buddhist Action Coalition shared the article, commenting that “social justice activism is also done in how we respond to diversity and difference in our sanghas.” Priya Friday-Pabros said, “Thank you for this. As a woman of color, I get it.” But Ralph Johnson wrote that as a person of color, he “often finds these kinds of issues confusing and useless,” while Ron Huybrechts remarked that “the introduction of identity politics into Buddhist practice is unnecessary and unhelpful.” Readers also debated the place of minority-only Buddhist communities. Kenny Craig offered sympathy for Sattar’s experiences but felt it was “sad” that “to find acceptance in a sangha you had to practice with a teacher and fellow meditators with similar skin color. In my opinion, both situations miss the core of the teachings that you’re devoted to.”

The Question

How do people react when you tell them you’re Buddhist?

Mostly people are surprised or a little curious but don’t ask anything further, although the Jehovah’s Witnesses who come to my door simply stare as though they don’t believe me. The funny thing is, I ran into a coworker when I began going to dharma talks at a new Zen center in my area. We both laughed, because even though we were friends at work and spoke often, we didn’t know that we were both practicing Buddhists until that moment.

—Dawn Woodward

I live in the South, and if you even say “Namaste” they run like you worship the devil. (OK, that’s exaggerating a little, but not much.)

—Sandy Emory Lawrence

Once a stranger at a tram stop said to me, “I’m Christian.” I said, “That’s nice, I’m Buddhist.” She replied, “Oh, what a pity, God loves you anyway.”

—@Zomog

For the Next Issue:

How did you know you had found the right school or sangha for you? Email editorial@tricycle.org.

♦

Send letters to editorial@tricycle.com, post a comment on tricycle.org, or tweet us at @tricyclemag.