In the mid-1970s and ’80s, when I was a resident at the Zen Center of Los Angeles, we would, during periods of formal practice, recite a chant with our meals, the core of which was an invocation of Mahayana Buddhism’s pantheon of Buddhas and bodhisattvas. As with so many things about Zen ritual, no one ever explained the content of the chant; you just did it. But there was something odd and intriguing about this particular chant. There, where the recitation moves from the names of buddhas to the names of bodhisattvas—right at that juncture where the type of personification shifts—appears the name of a scripture: The Sutra of the Lotus of the Wonderful Law, or for short, the Lotus Sutra.

Even without an explanation, it is not so hard to get a handle on the reason for reciting the names of the buddhas and bodhisattvas. In doing so, one is honoring and evoking their presence and their mind. But why a sutra? And why, out of the hundreds of sutras in the Mahayana canon, the Lotus Sutra? What is the particular significance of this sutra? Even for a bookish Buddhist like me, this was puzzling.

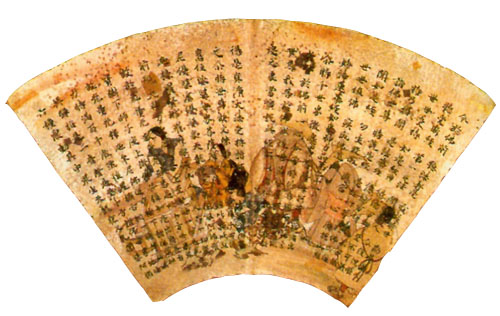

Little is known of the text’s origins, but according to legend, Shakyamuni Buddha preached the Lotus Sutra at the sacred Vulture Peak, in northern India. It is said to be the last of his discourses and was, according to some traditions, the culmination of his teachings, superseding all previous ones. Modern scholars estimate that the text was composed in the first or second century of the common era and was first written down in about the year 200, some six or seven centuries after the Buddha’s lifetime.

In his lectures, the abbot of the Zen Center, Taizan Maezumi Roshi, made occasional reference to the Lotus Sutra, usually to cite one of its parables. When he did, he would, likely as not, preface his remarks by saying that the Lotus is traditionally regarded as the “king of sutras.” But I can’t recall him ever lecturing on the sutra itself; neither can I think of a time when he encouraged us to study it. Indeed, one could easily devote years to Zen training and never once pick the thing up.

So I was a little surprised when, a year ago, my friend Michael Wenger told me that he was leading a practice period at the San Francisco Zen Center that would take as its focus the Lotus Sutra. Even though the study of sutras has historically been foundational to Buddhist practice, it doesn’t seem to have much appeal for most Western dharma students. We tend to prefer the writings of contemporary interpreters, and if we do look to traditional sources, it is usually to commentary literature. But sutras are, whether in fact or in legend or in both, the word of the Buddha, and the Lotus is, at least for the Buddhists of East Asia, perhaps the most esteemed of them all. So Michael’s plan to lead a course of study based on a text that has been for countless millions an abiding, unassailable, and fathomless source of wisdom and inspiration seemed, on inspection, like not such a bad idea.

Contemporary exponents of Buddhism tend to address contemporary issues facing a contemporary audience. But in the rush to relevance a feeling for the density and gravity of tradition can be lost. The sociologist Robert Bellah observes that, living as we do at a time when our social institutions are in alarming decline, contemporary forms of spirituality that exalt individualism—the personal journeys of individuals seeking spiritual self-interest—over community and tradition may be doing more to contribute to our social pathology than to ameliorate it. Religious traditions—at least ones that are vital—anchor individuals in a meaningful collective life. They provide a framework that links individual spiritual aspirations to communities extending deep into the past, far into the future, and outward into the long present. The recalcitrance of tradition pulls against the innovative stirrings of the individual talent, setting up a creative tension. That point of tension, between the self and the community to which the self is bonded, is the place where religion happens.

Because of its preeminence, the Lotus Sutra offers a unique glimpse into Buddhist history and tradition. Studying the Lotus, we witness the tradition at work on itself—critiquing and interpreting, amplifying this perspective and rejecting that one, solving one set of problems and creating new ones. For Western Buddhists, our relationship with the Lotus Sutra is largely unconscious. Yet, as the following articles attest, it runs deep. Indeed, the Lotus Sutra is so thoroughly inscribed in Buddhism in the West—and not only the meditation-oriented Buddhism favored by most Tricycle readers, but also the Nichiren and Pure Land traditions—that studying the sutra is something we engage in whether we know it or not. But it is, I think, best to know it. The Lotus Sutra is an essential Buddhist text, but it is hardly a representative one. In form, style, and content, it is a radical departure from all conventions. It is regarded less as a description of the path to awakening than as its evocation, as a direct presentation of the awakened mind itself. Which brings us back to the meal chant mentioned earlier. We might now regard the sutra’s inclusion in the roll call of buddhas and bodhisattvas as implying that it is more than a text, that it is, like those buddhas and bodhisattivas, an active and beneficent presence.

♦

This article is a part of the special section on the Lotus Sutra in Tricycle’s Spring 2006 issue. The other articles in this section are:

“Entering the Lotus”

by Michael Wenger

“A Greater Awakening”

by Jan Nattier

“The Towering Assembly”

by Tricycle

“Single-Practice Masters”

by Tricycle

“The Final Word: An Interview with Jacqueline Stone”

By Andrew Cooper