When I first came to Indiana University as an assistant professor in the fall of 1992, I taught a class in Mahayana Buddhism based on an in-depth reading of just two texts: the Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines and the Lotus Sutra. Enrolled in the course was a Tibetan Buddhist monk from India—I knew him simply as Thubten—who had come to Indiana as a Tibetan language instructor. Thubten’s contract required him to take a certain number of credit-hours each semester, and that is how he came to be my student. It was not until later that I learned that Thubten held a geshe degree, the Tibetan Buddhist equivalent of a Ph.D. In retrospect this was probably fortunate, since my ignorance of his status allowed me to treat him just like the other students (and, of course, prevented me from worrying about the possibility of his superior expertise on certain points!).

Despite his non-native English, Thubten had little trouble during the first part of the semester, when we were studying the Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines. Though he had never read that particular sutra, the Perfection of Wisdom tradition, as one of the “core courses” of his monastic education, was quite familiar to him. When we came to the Lotus Sutra, however, I noticed a decided change. Though it has been tremendously influential in East Asia, the Lotus is rarely studied by Tibetan Buddhists. As we worked our way through the text, Thubten looked baffled, even worried. At one point, he told me that he had gone to the library to check out the Tibetan version of the sutra, for he thought he must not be understanding the English version correctly. Finally one day in class he simply shook his head in amazement and exclaimed, “I can’t believe the Buddha would say such things!”

Thubten was caught in a classic Mahayana predicament. As a devoted Buddhist, he accepted the verdict of his tradition that all Mahayana scriptures were the word of the person we call the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni. But at the same time, it seemed quite clear to him that theLotus Sutra conflicted with much of what he, as a Mahayana Buddhist monk, had been taught.

I suspect that Thubten’s shock at encountering the Lotus was not, historically speaking, all that unusual. On the contrary, I think it might well have resembled in many ways what most Indian Buddhists in the first or second century C.E. felt when they first heard this very revolutionary text. For the Lotus does not only critique what some Mahayanists describe as the Hinayana (“lower vehicle”); it also contradicts much of what, at the time of its composition, was seen as constituting the Mahayana (“greater vehicle”) tradition as well.

Those familiar with secondary literature about Buddhism are likely to have the impression that the Mahayana emerged as a liberalizing movement within the Buddhist community, one that made the practice of Buddhism, and the attainment of awakening, available to a wider group than had previously been the case. Seen in this light, the Mahayana is often perceived as pro-laity, pro-family, even pro-women, and thus as a form of Buddhism particularly well adapted to the presumably more egalitarian societies of the world today. But it is becoming increasingly clear to scholars that this vision of the character of Mahayana Buddhism has been shaped by a very atypical text, namely, the Lotus Sutra .

For many students of Buddhism, the term Mahayana also has particular philosophical connotations: the belief in the emptiness of all phenomena, for example, or the understanding of the historical Buddha as a manifestation of ultimate reality, or of the dharmakaya (“dharma-body”). But when it first appeared, the term had none of these associations. The “greater vehicle” had, initially, one specific meaning. It was the vehicle, or path to awakening, of one intending to become a Buddha, which was the original meaning of the term bodhisattva. In other words, the word Mahayana, in its original usage, did not comprise any new doctrinal content whatsoever. It meant nothing more and nothing less than “the bodhisattva vehicle.” But it is not only the meaning of Mahayana that changed; other core terms—‚such as Buddha and bodhisattva—took on new meanings as well, and likewise, the goal of the Buddhist teachings came to be understood in new ways. During Shakyamuni Buddha’s own lifetime there was only one notion of what constituted awakening. The Buddha was seen as far greater than his followers, primarily because he had discovered the path to awakening for himself and thus made things far easier for those who would follow in his footsteps. But the nature of awakening itself—understood, in a general sense, as “seeing reality as it is”—was believed to be in every case identical. Indeed, Shakyamuni himself was, like his awakened followers, referred to as an arhat (literally “one who is worthy of respect”).

With time, however, the status accorded to the Buddha’s awakening rose, while that of his awakened followers—still known as arhats—declined, at least in some circles. Accordingly, within a few generations we find indications of a substantial difference in valuation between the Buddha (whose awakening is now referred to as “Supreme Perfect Awakening”) and the arhat (whose awakening is generally still referred to as “nirvana”). The Buddha’s awakening is now described as qualitatively greater, involving a degree of knowledge and insight not shared by an arhat. Of the two levels of realization, the arhat’s status is distinctly second class.

Not surprisingly, as this discrepancy became ever more sharply felt, some in the Buddhist monastic community were no longer satisfied to strive for “mere” arhatship. A growing number came to consider arhatship as something to be avoided, a “private nirvana” that would naturally result from intensive Buddhist practice unless something was done to prevent it. That “something” was the vow to attain a different goal—that is, the vow to instead become a Buddha.

Inspired both by stories of Shakyamuni’s years of asceticism and intensive self-cultivation in the wilderness prior to his awakening and by jataka stories describing his previous lives, some Buddhist monastics began to envision a far more rigorous and time-consuming path leading to the full awakening of a Buddha. Would-be bodhisattvas had to look forward to thousands, if not millions, of additional lives before Buddhahood could be attained. Further, it was assumed that in those lives they would perform the kind of extreme acts of self-sacrifice described in the jatakas, in which, for example, the Buddha-to-be, out of compassion, allows himself to be devoured by a hungry tigress and her cubs or to be cut to pieces by an evil king.

In the Lotus Sutra we hear that the attainment of Buddhahood is not the result of aeons of self-sacrifice but is far easier than had previously been supposed.

The pioneers of the bodhisattva path might well have viewed themselves as an elite destined for a higher goal than their monastic compatriots, but they did not, at this point, separate themselves from those who were striving for arhatship. In all likelihood, in fact, these early bodhisattvas constituted a relatively small group living within a monastic environment consisting largely of those who still had arhatship as their goal. These early volunteers for the bodhisattva track did not subscribe to the “signature” doctrines of later Mahayana philosophical schools—the emptiness of all phenomena, the ten stages of the bodhisattva path, the three “bodies” of the Buddha, and so forth—for all these had yet to emerge. They were simply a group of unusually ambitious and compassionate individuals who had dedicated themselves to doing whatever it takes to obtain Buddhahood rather than arhatship. But since the very definition of a Buddha is someone who discovers the way to awakening by himself in a world that knows nothing of Buddhism, they could not become Buddhas here and now. Rather, that final step had to be reserved for another time and (in most cases) another world-system. So the aim of these pioneering bodhisattvas entailed “rediscovering” Buddhism for the benefit of all beings in the distant future, when the teachings of previous Buddhas had long since been forgotten.

Given this scenario, the possibility of arhatship becomes, ironically, a threat. The early Mahayana scriptures still regarded its attainment as quite accessible even within this present lifetime. Meditation—especially the practice of the dhyanas (Pali, jhanas), or states of concentrative absorption—is viewed as a particular danger, since the budding bodhisattva may inadvertently “tumble into” arhatship. This is why the bodhisattva is warned in thePerfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Lines, for example, to use his “skillful means” to avoid accidentally attaining nirvana. The bodhisattva must walk a tightrope, as it were, cultivating advanced meditational practices while staving off what would be their natural result.

It is against such a background that we encounter—in the first or second century C.E.—a radical departure from this consensus. In the Lotus Sutra we hear that arhatship is not a genuine alternative destination, but that all Buddhist practitioners—not just a few—are en route to Buddhahood. We hear that the attainment of Buddhahood is not the result of aeons of self-sacrifice but is far easier than had previously been supposed, and that even a child who builds a stupa out of sand will one day become a Buddha. We are told that Shakyamuni was not simply a man who experienced awakening under the Bodhi tree but one who had already been awakened long before he came into our world. We hear further that he did not at his death really enter the extinction of final nirvana but simply appeared to do so for the benefit of his followers. The assumption that there can only be one Buddha per world-system at a time is challenged by the memorable scene of Shakyamuni and the ancient Buddha Prabhutaratna, or Many Treasures Buddha, sharing seats within a stupa in the sky. Finally, the Lotus gives a new meaning to the term “skillful means”: rather than a balancing act to avoid falling into arhatship, skillful means is now understood as a technique used in teaching other beings, specifically the adaptation of the content of one’s teachings to suit their needs. In short, virtually every one of the key assumptions of early Mahayana Buddhism has been radically overturned.

Virtually every one of the key assumptions of early Mahayana Buddhism has been radically overturned.

It is easy to see that such a message might well have been shocking. To those who aspired to attain arhatship, not to mention those who had already reached that goal, the Lotus Sutrasays that their spiritual ideal is merely an illusion. And as for the Mahayanists, if a simple offering made by a child can ensure the attainment of Buddhahood, to what end have bodhisattvas been exerting themselves in the cultivation of the six perfections (paramitas), up to and including the renunciation of their own lives? Have all their efforts, like those of the practitioners who thought they had attained “real” arhatship, been in vain? The Lotus seems to suggest as much when it argues that minimal acts of devotion, and above all faith in the sutra itself, are sufficient guarantors of one’s eventual Buddhahood.

We are so used to hearing (once again, partly under the influence of the Lotus) of the opposition between Hinayana and Mahayana Buddhists that we are not inclined to see much commonality between these two camps. But the Lotus Sutra challenged a basic assumption about the nature of the Buddhist path shared by both the proponents of the nirvana of the arhat and the advocates of the newer option to “go for the gold” of Buddhahood. For both groups saw Buddhist practice as a path—that is, as a prolonged process of step-by-step self-cultivation.

As path-centered models of the religious life, both the traditional route leading to arhatship and the newer bodhisattva vehicle are examples of what Karl Potter, in his classic work Presuppositions of India’s Philosophies, calls “progress philosophies,” which describe liberation as the result of a gradual process of deliberate spiritual cultivation. Contrasted with this model are what Potter calls “leap philosophies,” according to which liberation takes place all at once and has no direct correlation to acts of self-cultivation.

From the viewpoint of a leap philosophy, there is no causal connection between the liberated and the unliberated state; it is, therefore, impossible to build a bridge between these two wholly incompatible realms. If it is not possible to create a causal chain that will lead one from unliberated to liberated status, and yet, as is claimed, liberation is possible, it must be the case that liberation is already in effect. All we must do as practitioners is allow ourselves to see, and to acknowledge, that fact.

The “leap” to the liberated state occurs as a sudden insight. Depending on the Indian philosophical school in question, this breakthrough might be provoked by the undermining of one’s treasured rational categories (as in the Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna’s method of dialectical analysis), by hearing a verse from a sacred text (as was proposed by the Advaita philosopher Sureshvara), or by the grace of God alone (as asserted by the theistic philosopher Madhva). But whatever the context in which this sudden realization takes place, it is not the gradual result of self-cultivation. Even for the subgroup Potter terms the “do-it-yourself ” leap philosophers, who maintain that certain obstacles in the way of realization can be removed by one’s own effort, there is nothing one can do that can cause realization to occur. In the Lotus we see articulated a Buddhist leap philosophy, one that specifically challenged the progress philosophies of aspirants to arhatship and to Buddhahood alike. It has long been noted—not only by modern scholars but also by traditional Buddhist teachers—that the Lotus is singularly short on instructions for how to practice the path. But it is not as though the compilers of the sutra simply forgot to include that part. Rather, in the Lotus the very idea of a path is radically undermined. Instead, practice is fulfilled by accepting, in all humility, Shakyamuni’s word that through faith one will attain Buddhahood in the future. As the closing lines of chapter 2 of the sutra put it, “Have no further doubts; rejoice greatly in your hearts, knowing that you will become Buddhas.”

It is this, I suspect, that was the primary cause of Thubten’s consternation. Although Tibetan Buddhism has largely jettisoned arhatship as a valid goal, it has maintained a strong commitment to the notion of spiritual cultivation. To hear the Buddha proclaim that every practitioner is destined for Buddhahood—even those who, like the legendary betrayer of the dharma, Devadatta, are guilty of heinous crimes—would seem to subvert the very foundation of the long and demanding practice of the bodhisattva path.

But there is more at stake here than the individual’s spiritual practice, for rejection of the “progress” model has an institutional corollary as well. A progress philosophy necessarily entails a hierarchical community structure. As long as spiritual advancement is a matter of individual self-cultivation, members of the Buddhist community will necessarily be located at different levels on a hierarchical scale. In other words, the manner in which practice is construed also implies a particular style of social organization. In the case of progress philosophies, this means that different members of a given religious organization are understood as having made different degrees of progress, and thus they may be assigned to different spiritual ranks.

Leap philosophies, by contrast, tend to level such spiritual hierarchies. Instead, we find a sharp distinction between those who have and those who have not made the “leap” in question: a distinction between those who have come to see reality clearly, or have accepted the Buddha’s message, or have been ”saved” (to use the terminology of Evangelical Christianity, which is another leap philosophy), and those who have not. Within each of these two camps, however, we see a radical egalitarianism: all who have made the leap (however construed) have equally attained the goal, while all who have not are equally cut off from it.

Students of Buddhism, especially of its history, will note that Potter’s categories of leap and progress philosophies correspond, significantly though not entirely, to those of the longstanding debate about sudden versus gradual awakening. Although the polemics put forth by the advocates of sudden and gradual approaches assume a sharp distinction between the two, in practice—as scholarship has shown—the differences are generally more a matter of emphasis. Those who practice gradual self-cultivation usually recognize that their path includes moments of sudden insight, while those who give primacy to sudden realization generally acknowledge that one must make persistent effort to carry that realization into one’s daily life.

Contemporary readers do not always take the Lotus Sutra literally, of course, and though it embodies the qualities of a leap philosophy, this scripture has, throughout its history, provided the basis and inspiration not only for all-at-once leaps of faith but also for diligent step-by-step progress. Still, we should not deny the radical nature of its message. The sutra offers a model of spiritual life that is very different from those based on the metaphor of a path, challenging those who would measure their attainment in retreats practiced or insights accumulated or virtues exhibited. For those who would posit a one-to-one relationship between the effort one puts forth and the outcome one achieves, it speaks of the transformative power of faith in the awakened mind itself. It suggests that, through faith in its message, one makes the Buddha’s intention, rather than one’s own, the pivot of practice.

♦

This article is a part of the special section on the Lotus Sutra in Tricycle’s Spring 2006 issue. The other articles in this section are:

“Entering the Lotus”

by Michael Wenger

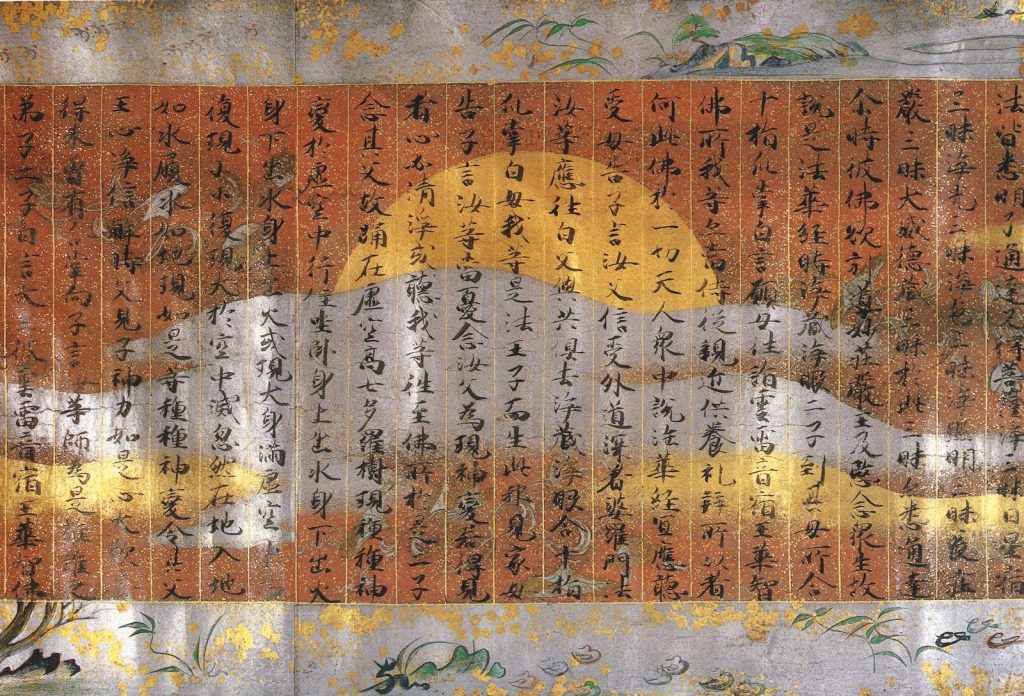

“The Towering Assembly”

by Tricycle

“Single-Practice Masters”

by Tricycle

“The Lotus of the Wonderful Law”

by Andrew Cooper

“The Final Word: An Interview with Jacqueline Stone”

By Andrew Cooper

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.