Opinions attract their own kind. Offer one and you get one in return. This can be true of even the most benign assertion. The fact that you like peaches obligates others to declare their preference for oranges. I do this myself frequently enough to wonder what attraction opinions hold for me. And I suspect that having an opinion is a way to stake out a secure and identifying mental territory for myself. Who would I be without an opinion?

When someone’s giving his view of things, I’ve caught myself taking a position before he’s even finished laying out his point. It’s a contagious sort of reaction that’s greatly magnified when an opinion concerns the moral right or wrong of something. Judgments on right and wrong are a nearly irresistible enticement to pick sides. And that’s exactly why the old Zen masters warned against becoming a person of right and wrong. It isn’t that the masters were indifferent to questions of ethics, but for them ethical conduct went beyond simply taking the prescribed right side. For these masters, the source of ethical conduct is found in the way things are, circumstance itself: unfiltered immediate reality reveals what is needed.

I’m sure you can appreciate how contrary this is to traditional ethics, even the more traditional Buddhist ethics. When I first encountered this teaching in Zen, I simply couldn’t get it at first. Among the farm people where I grew up you were expected to know right from wrong. And the right and wrong you were expected to know was of a consistent sort that could be recited, chapter and verse, when the occasion required it. Those who couldn’t do so were disparaged as ones who “don’t know right from wrong.” That’s how traditional ethics works: conduct is based on reference to fixed principles. But this approach is limited, because any fixed ethical principle is a generalization, while events are specific. A precept such as “Do not kill,” “Do not steal,” or “Do not lie” applies to a respective category of human behavior. Since an actual event isn’t a category, ethical precepts serve us best not as an immediate dictate of behavior but as an instrument of inquiry. Daishin Morgan of the Soto Order of Buddhist Contemplatives taught that the purpose of the precepts is “to guide us beyond their form in a legalistic sense to the spirit that lies behind them.” The precepts are something to live with rather than live by, and living with the Zen precepts is ultimately humbling, softening our hearts to accept our own imperfections and deepening our resolve to live without harm.

If I want to see clearly what’s happening now, I must put aside external points of reference. What’s happening now is neither what happened before nor what I might hypothetically imagine happening in the future. As Erich Fromm said, “Contact is the perception of differences.” While an ethical generalization is derived from perceived similarity, a discrete event is made specific by virtue of difference. If an event seems familiar, it’s a likely lapse in attention that makes it so. The Chinese Ch’an masters saw that the most unassailable right or wrong is also the most likely to lure us away from present reality, substituting in its stead a familiar and comforting perception. All of us on the neighboring farms, children and adults, gave homage to the ancient ethic of not killing. “Do not kill” was understood among us as an undeniable good urging us to preserve life. But when a farm cat I’d raised from infancy dragged herself onto the porch steps, its hindquarters and legs crushed beyond saving, I put her to death. And only afterward did I weep with regret at the life I’d brought to an end.

Once, my mother on her way out the door to a women’s tea asked me how I liked a hat she’d bought for the occasion. I thought the hat was perfectly horrid. She was such a beautiful woman. It seemed a shame to let her go looking that way, but I lied and told her the hat was lovely. Was I wrong to do so? I certainly broke the literal precept. But I would have violated the promptings of a sympathetic heart had I told her the truth. The living moment exposes the limits of principled behavior. Yet it’s also true that Buddhism has developed and stated certain ethical principles. The very first teachings of the enlightened Gautama included the teachings of Right Speech, Right Action, and Right Livelihood. And from these first teachings have been derived a series of stated precepts that Zen Buddhists accept and practice to the best of their ability. Most of these precepts will seem indistinguishable from the ethical principles of other religious and philosophical systems. Zen Buddhists formally vow to take up the way of not killing, not stealing, not speaking falsely, and so on, and these precepts combine to support the overriding Buddhist ethic of noninjury.

Zen ethical principles, like all systems of ethics, are derived from an exhaustive observation of life and are a synthesis of painstaking induction. So where does the critical difference lie between Zen ethics and other traditional ethical systems? It lies in the way a Zen Buddhist works with ethical principles. For the Zen Buddhist, an ethical precept is a question to be held up to the light of circumstance, an inquiry rather than an answer. And the nature of this inquiry is not so much the dubious enterprise of trying to figure out the right thing to do as it is an offering of an unaided heart. After all, it’s from this heart of ours that the precepts themselves once arose. At the threshold of choice, the Zen Buddhist trusts this ancient heart above all other authority. It’s not that the Zen Buddhist reinvents the ethical wheel every time he faces a new situation; it’s just that he goes back to the source itself. Ethics is not an invention but an expression of the heart’s core. What’s most needed in the moment of choice is an empty hand.

The person of right and wrong for whom right is always right and wrong is always wrong never risks an empty hand. I’ve discovered that when I advocate from a moral persuasion and I’m wrong, I can be pretty hard to take. But when I’m right I’m insufferable. My “rightness” leaves me vulnerable to my own arbitrary judgment of the matter. “A Place Where We Are Right,” a poem by the Israeli poet Yehudi Amichai, shows this consequence perfectly:

From the place where we are right

Flowers will never grow

In the spring.

The place where we are right

Is hard and trampled

Like a yard.

But doubts and loves

Dig up the world

Like a mole, a plow.

And a whisper will be heard in the place

Where the ruined

House once stood.

(from The Selected Poetry of Yehudi Amichai, translation by Chana Bloch and Stephen Mitchell, University of California Press, 1996, used with permission of the translators)

Zen ethics is grounded in the realization that one does not know what’s right. This “not-knowing” is the refuge from which all moral action originates. It’s a refuge that can’t be relegated to the role of moral abstraction and remains a free and alive expression of the moment. What’s offered us in the place of moral certainty is doubt and love, which are nearly synonymous. Doubt wears the hard edges off our best ideas and exposes us to the world as it is. When the great Zen master Ikkyu was asked, “What is Zen?” He replied, “Attention! Attention! Attention!”

This very attention to a world that’s not of our contrivance is an act of love, for we can only love what we truly see. I can testify to this in the most mundane way, as can any of us. But here’s an example. I was once traveling in a car with a friend, and a mosquito kept buzzing around my face and neck until eventually I felt the telltale itch that told me the mosquito had fed. And then it appeared on the windshield of the car, its tiny body made translucent against the sunlight. I could actually see a little red thread of my own blood shimmering inside the mosquito, and I was touched with admiration and affection for this beautiful creature whose eggs would feed on an offering of my own body. I said to my friend, “Look, Ralph, you can see my blood in the mosquito’s body.” And before I could object, he’d smashed the mosquito with the flat of his hand, leaving nothing but a red smear on the glass. I don’t blame Ralph. I’d looked and he hadn’t. We touch here the crux of Zen ethics that equates simple mindfulness with the capacity to love. And what else is moral action if it isn’t compassionate responses? We don’t get love from principles; we get love from occupying the ground we stand on.

And the ground we stand on is a field without signposts, in which we must find our way without conventional supports. There is a passage in Sarah Orne Jewett’s The Country of the Pointed Firs that aptly describes the nature of our situation. Almiry Todd, a character who while describing a tree could just as well be describing herself, says,

There’s sometimes a good hearty tree growin’ right out of the bare rock, out o’ some crack that just holds the roots, right on the pitch o’ one of them bare stony hills where you can’t seem to see a wheel-barrowfull o’ good earth in a place, but that tree’ll keep a green top in the driest summer. You lay your ear down to the ground an’ you’ll hear a little stream runnin’. Every such tree has got its own living spring; there’s folk made to match ’em.

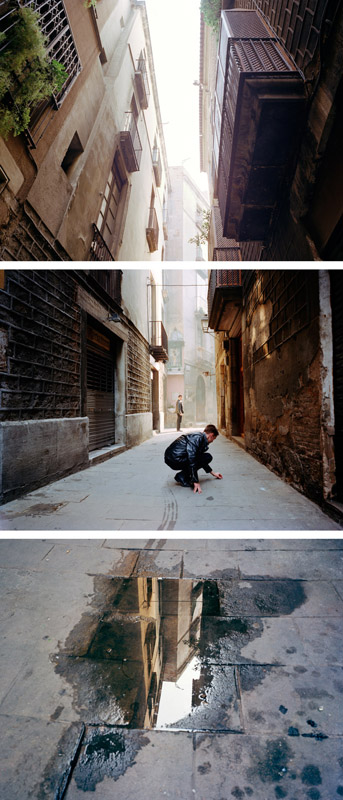

While a Zen Buddhist may cherish and recite her preceptual vows each day of her life, she nonetheless learns to keep her ear to the ground, listening to her own living spring and trusting that above all else. She receives the waters unwittingly, the living spring flowing into her from all sides—the scrape of shoes on the city street, the studied precision of the cook cleaning the kitchen counter, the girl swinging her hair with a twist of her neck, the guard with his feet planted, an old woman’s cough heard from an adjacent room, a hand nervously clenching and opening, the tone a voice takes, a hesitation in mid-sentence, a child snatching at a pebble sunk in the creek. She doesn’t accumulate these bits and facts of life like evidence on which to base a judgment. She doesn’t accumulate anything at all, nor does she form an impression of what she sees and hears. She lets the waters enter her body like sap rising from roots. She trusts that the limbs will grow in their own way and that the leaves will unfold in time.

It’s possible to do good and equally possible to do harm, and so we’re stuck with the necessity of choice and consequence. And no choice can ever be encompassing and conclusive because the moment is a movement and requires continual adaptation and adjustment. We can faithfully adhere to a precept, and yet end up doing irreparable harm. We can never trace the ultimate consequence of our choices, but it’s safe to conclude that whatever we decide to do will be fraught with certain error and fall short of the best intent. An old Christian story attributed to the Desert Fathers touches on this human fallibility. The story goes that a monk asked Abba Sisoius, “What am I to do since I have fallen?” The Abba replied, “Get up.” “I did get up, but I fell again,” the monk told him. “Get up again,” said the Abba. “I did, but I must admit that I fell once again. So what should I do?” “Never fall down without getting up,” the Abba concluded. Falling down is what we humans do. If we can acknowledge that fact, judgment softens and we allow the world to be as it is, forgiving ourselves and others for our humanity. The Buddha’s First Noble Truth—that suffering exists—is, in itself, a permission to be human and not demand more of ourselves than we’re capable of. Our compassion arises from our very fallibility, and love takes root in the soils of human error.

Knowing that we’re certain to make crucial mistakes from which suffering will follow, we seek moral redemption through sustained attention. We stay around to clean up the mess we’ve made. If we really want to keep the Buddha’s house in order, we can’t afford to hold anything of ourselves in reserve. To be truly and wholly present even for the briefest moment is to be vulnerable, for we have arrived at the point where the obstacle that fear constructs between ourselves and others dissolves. It is here that the heart is drawn out of hiding and the inherent sympathetic response called compassion arises. We cease seeking our own personal happiness at the expense of others, because we see that the suffering of others is our suffering as well, and we see that our happiness too is inseparable from that of others. This expansion of self is what it means to be whole: it’s what we truly are when the living spring of compassion wells up in us, watering the deserts of discord and distrust with a love that can’t be turned aside. Ethical response is just such an unasked and unimpeded flow; it’s not a talent I can perfect and carry around with me and apply to situations. It’s always new, always for the first time.

The old masters placed the site of ethics within the inward, instantaneous and entire grasping of circumstances, a living dharma not divisible into categories of right and wrong. We can know things most directly when we lay no claim to knowing anything at all. The Zen Buddhist does not ask what’s right and wrong but rather, “What am I to do at this moment?” She has no opinion to put forth. She has learned not to acquire answers, and so holds her question open wherever she goes.