Beauty has always been for Buddhism an intractable koan, a conundrum it has never quite resolved. To most of us, a life without beauty would seem scarcely worth living at all, and yet the dharma has kept it at arm’s length for the last twenty-five centuries.

With any other subject that matters now—ethics, politics, gender, neuroscience, and the environment—Buddhism has engaged fearlessly, the resulting dialogues producing an array of concepts and paradigms that enrich our understanding of the path. But beauty isn’t just overlooked. It’s actively ignored or anxiously repressed, and for a host of very good reasons. For one, it takes us straight to the deep divides separating Buddhist Asia from the West. Not only that, it threatens to expose the fault lines fracturing the dharma itself. Talk of beauty can easily devolve into quarrels over whether or not the senses prevent us from waking up. And where we land on the senses will decide how much at home, or how much at odds, we feel with this world.

It’s certainly true that the dharma arose out of an older South Asian tradition that saw the world as unsatisfactory and therefore better renounced. For the beautiful, this austerity had no time; but when we look to the ancient Greeks, we find the very opposite, an embrace of the world so exuberant that the great philosophers thought beauty, truth, and goodness to be one and the same. And here, with these two conflicting sensibilities—renunciation versus acceptance—our East-West dialogue on beauty halts, or so it appears. But really the matter is more complex. Consider the following verses from the Greek poet Theognis of Megara:

Best of all things is never to be born,

never to know the light of sharp sun.

But being born, then best

to pass [along as] quickly as one can

–trans. Willis Barnstone

As an educated Athenian, Plato would have known these then-famous lines, and while he held beauty in high regard, it wasn’t a beauty we’d recognize today. The journey to wisdom starts, Plato taught, when we observe “the beauties of earth,” but then, “mount upwards,” leaving them far behind (Symposium, 211 c-d, trans. Benjamin Jowett). The senses have value only as guides, necessary but unreliable, to the goal of reunion with an eternal Mind, beautiful in its transcendence of physical existence.

If these unexpected details complicate our thinking about beauty in the West, looking more closely at Buddhism will reveal a parallel complexity. Whenever the Buddha wanted to describe the essence of his teaching, he consistently chose the same word. “This dharma,” he announced, “is beautiful at the beginning, beautiful in the middle and beautiful at the end.” The repetition here in English mirrors faithfully the rhythm of the Pali suttas where the Buddha says kalyana, “beautiful,” three times: adikalyana majjhekalyana pariyosanakalyana. It may come as a surprise to learn that kalyana shares an Indo-European root with kallos, the Classical Greek word for beauty. But maybe it shouldn’t surprise us at all.

Related: Renunciation by Pema Chödrön

When we come to beauty—and also to the ambivalence inspired by the senses—Buddhist Asia and the West may actually converge or, perhaps, have never parted company. World-embracing and world-renouncing attitudes turn up in both cultural spheres, and they also cut across the boundary marking off the Theravada of the South from the Mahayana of the North. But the matter becomes even more complex if embracing and renouncing aren’t opposites at all but polarities—positive and negative poles that generate the energy we need to set us free. In Zen, we prefer the phrase “not-two” when others may simply say “the one,” because we’re convinced that real unity has to include the differences. And in the case of beauty, the “not-two” requires both world-embracing and world-renouncing, skillfully balanced to show us the way.

I’m aware that it’s difficult to make this case when we turn to the Buddha’s own advice in the so-called Fire Sermon, the Adittapariyaya Sutta. There, without apology or hedging, he deprecates the senses. Mental contact with the world leads to sensation, he declares, and sensation to attachment, the source of suffering:

Monks, the All is aflame. What All is aflame? The eye is aflame. Forms are aflame. Consciousness at the eye is aflame. Contact at the eye is aflame. And whatever there is that arises in dependence on contact at the eye—experienced as pleasure, pain or neither plea- sure-nor-pain—that too is aflame. Aflame with what? Aflame with the fire of passion, the fire of aversion, the fire of delusion. Aflame, I tell you, with birth, aging and death, with sorrows, lamentations, pains, distresses, and despairs.

–trans. Thanissaro Bhikkhu

Not only sight but the other senses, too—hearing, touching, tasting, smelling, and thought, which early Buddhists counted as the sixth sense—get the same rough treatment here. It’s unsurprising, then, that the World Honored One prescribes as the antidote nibbida, “disenchantment” or a “turning away”:

Seeing thus, the well-instructed disciple of the noble ones grows disenchanted with the eye, disenchanted with forms, disenchanted with consciousness at the eye, disenchanted with contact at the eye. And whatever there is that arises in dependence on contact at the eye, experienced as pleasure, pain or neither-pleasure-nor-pain: With that, too, he grows disenchanted.

If disenchantment takes us to awakening, the case for beauty looks like quite a stretch. What kind of beauty can exist, after all, once we renounce “contact at the eye”? And the Pali suttas aren’t alone with their apparent rejection of the senses. In verse 26 of the Diamond Sutra, a core text for the Mahayana, the Buddha doesn’t pull any punches when he tells his disciple Subhuti, “He who sees me in form, he who seeks me in sound, wrongly turned are his footsteps” (trans. Zen Studies Society).

And yet, before we make up our minds about beauty’s role, we should recall that since the dharma’s early days, sculpture, painting, architecture and design, poetry, plays, and an array of lively prose narratives have occupied a central place in the cultures fashioned by the Buddha’s followers. Anyone who has seen the haunting frescoes on the walls of Ajanta’s caves or the reliefs carved on the gates of the Great Stupa at Sanchi can testify to the power of the art that the dharma has inspired. And to these examples we could add China’s Mogao grottoes, or Ginkakuji, the Silver Pavilion temple in Japan, or the breathtaking Potala palace in Tibet. Since the second or third century CE, Buddhists have recited the Diamond Sutra’s lines about the footsteps gone astray while facing brilliantly polychromed statues of the Sixteen Arhats or Guanyin, at ease in her jewelry and sumptuous robes.

Given what the Fire Sermon says, maybe those devotees should have looked away, but by doing so they might have missed the point, which is not what they saw but how they looked. And looking skillfully involves not only renouncing but embracing, too. Yes, “contact at the eye” is so dangerous that the word nibbida, “disenchantment,” can imply something even stronger—“revulsion.” We may need revulsion’s force to break the spell cast over us by the senses, which crowd our attention until we forget about the space that opens up between bare awareness and its objects. Every form of meditation that I know depends on discovering that space of emptiness, but if we stop there, we’ve traveled only half the way.

Recounting what happened after his enlightenment in the sutra known as “The Noble Search” (Ariyapariyesana Sutta), the Buddha tells his hearers this: “Having crossed over” to the other shore, an awakened person lives “unattached in the world. Carefree he walks, care-free he stands, carefree he sits, carefree he lies down” (trans. Thanissaro Bhikkhu). When people imagine how it feels to wake up as the Buddha did, a word like “carefree” may not spring to mind. But that’s probably because “other shore” suggests some remote, immaterial plane outside of our bodies. But in the “Noble Search,” we have it from the Buddha’s mouth—or, at least, from the monks who composed the written text— that enlightened people differ from the rest of us only in relinquishing the illusion of a separate, permanent self. Present in the world but “unattached” to the “I,” they still experience embodiment, which includes sensation and, at least potentially, the experience of beauty.

Regrettably, the sutta neglects to describe the actual moment when the Buddha “crossed over.” But for about fifteen centuries, Chan Buddhists have believed they know what happened. Chan/Zen tradition holds that on the eighth day of the twelfth lunar month, Siddhartha became fully enlightened when, looking up, he beheld the morning star. Redirecting his attention from emptiness back into the realm of form, he finally came face to face with the radiance of the dharmakaya, the ultimate reality.

Seeing wakes Siddhartha up. Even if the senses are often obstacles just as the “Fire Sermon” claims, they’re also allies that he couldn’t do without. Almost certainly, the Buddha had observed the morning star many times before, but now he views it in a liberating way by becoming one with it and with everything. After that, his own sensations seem no different from the passing of the clouds and the sound of the wind— like the sensations of a single, great body. And Siddhartha wasn’t the only one. Countless Zen stories describe practitioners making the same U-turn from emptiness to form. In one account, a disappointed monk, after decades of unsuccessful practice, leaves his monastery for a hermit’s hut. Then, one day, as he rakes gravel in the yard, his illusions completely dissipate when he hears a single pebble softly ping against a bamboo stalk. Another well-known vignette records that a monk wakes up when he gets slapped across the face; still another tells of a novice who hears his teacher say two words: “Ordinary mind.”

In modern times, perhaps the most famous case involves the Chinese monk Hsuyun (Empty Cloud), widely regarded as the preeminent Chan master of the last two centuries. At the age of 56, on his way to a twelve-week meditation retreat at Gaomin monastery in Yangzhou, Hsuyun nearly died after tumbling into the freezing Datong River. Sick and exhausted when he reached Gaomin, he gradually felt his energy return. Then, as he later wrote in his autobiography, “all my thoughts [came] to an abrupt halt,” and “my practice took effect throughout day and night.” On the third evening of the retreat’s eighth week, Hsuyun finally broke through:

An attendant came to fill our cups with tea after the meditation session ended. The boiling liquid accidentally splashed over my hand and I dropped the cup which fell to the ground and shattered with a loud report; instantaneously, I cut off my last doubt about the Mind-root and rejoiced at the realization of my cherished aim. . . . I then chanted the following gatha [enlightenment poem]:

A cup fell to the ground

With a sound clearly heard.

As space was pulverized

The mad mind came to a stop.

—trans. Lu Kuanyu and Richard Hunn

The Buddha saw the morning star; Hsuyun heard the impact of the cup. But in both accounts, the senses play a catalyzing role by uniting emptiness with form, renunciation with embracing.

Stories like Hsuyun’s turn up everywhere in Zen, and that makes it easy for us to overlook the challenge they pose to the way we might conceive of enlightenment. Yes, those stories clearly show that emptiness alone can’t awaken us. And yes, they demonstrate quite powerfully that we need the element of form as well. But even when we have both form and emptiness, there is still a final step, as we learn from a text that has always enjoyed a special prominence in Chinese Buddhism: the Shurangama Sutra.

In both the Buddha’s and Hsuyun’s accounts, the senses play a catalyzing role in enlightenment by uniting emptiness with form.

Early on, the Shurangama relates that in commemoration of his father’s death, King Prasenajit of Kosala invites the Buddha and his monks to the palace for a vegetarian feast. But when the retinue sets off, one important person is missing: the Buddha’s cousin Ananda, who is still in the city of Shravasti. Alone and having eaten nothing since the day before, Ananda wends his way through the city’s streets with his begging bowl until he comes to a house of prostitution. Through a doorway he catches sight of Matangi, a chandala, an untouchable woman, barely clothed and ravishing, who uses “Kapila magic” to draw him near.

Today, we might describe this magic as the power of materialism, which we Americans know quite well without, I think, fully understanding it. “Kapila” refers to the non-Buddhist Samkhya school that divides the world into matter and mind. Under the influence of this mistaken view, people will regard every- one and everything as objects separate from themselves because they haven’t yet discovered the emptiness that ties together the world of form. And “separate” is exactly how Ananda sees the prostitute. As for Matangi, her next meal depends on her skill at encouraging her clients to objectify her. So enchanted are they both by the Kapila spell that as Ananda’s resolve melts away, he prepares to break his vow of celibacy.

But back at the palace, the Buddha knows everything that’s happening, and he commands the bodhisattva Manjushri to transport himself magically to Ananda’s side before his cousin commits the misdeed. Later, after the banquet is through, Ananda throws himself at the Buddha’s feet, shaken by his inability to resist temptation. Moved at this distress, the Buddha asks him to recall what had drawn him to the dharma at the start. Maybe to Ananda’s own surprise—and, very likely, to ours— he answers that he was attracted first of all by the beauty of the Buddha’s body, with its “thirty-two excellent characteristics and the shining crystal-like form.” Although readers of the sutra in modern times may assume that people long ago would have reacted differently to this revelation, Ananda’s remarks betray the same anxiety that many of us now may feel about our sensual attachments:

I thought that all this could not be the result of [sensuous] desire and love [for the Buddha because] desire creates foul and fetid impurities like pus and blood which mingle and cannot produce the wondrous brightness of His golden-hued body, in admiration of which I shaved my head to follow Him.

–trans. Lu Kuanyu

Remember that when Ananda met Matangi, it was likewise her body that attracted him. In both cases, beauty acted as his guide, but in one, it nearly caused his moral defeat, whereas in the other it inspired him to pursue the highest wisdom.

While Ananda can recall every word he has heard the Buddha speak, he admits that his practice remains incomplete. Even though he has often entered samadhi—a deep, selfless concentration—his mind always stops with his sensations or withdraws from them into emptiness. Never has he traced those sensations back to the point where form and emptiness converge, and that’s why he fell apart at the crucial moment. As the Buddha goes on to explain,

[all] living beings, since the time without beginning, have been subject continuously to birth and death because they do not know the permanent True Mind whose substance is, by nature, pure and bright. . . . .The Tathagata [the Buddha] has always said that all phenomena are manifestations of Mind and that all causes and effects . . . take shape solely because of that Mind.

When Ananda lusted after Matangi and then averted his eyes in shame, both responses failed to set him free because he continued to believe, Kapila-style, in a material reality separate from himself. And that confusion kept him from noticing something even more important. As the Shurangama maintains, our minds unconsciously fabricate what we perceive to be “real,” braiding the strands of sensation and thought like the weaving of a vivid tapestry. Precisely because the whole process unfolds below the surface of our attention, it normally continues without our noticing. Yet when an unexpected shock—a slap in the face, the smashing of a cup—brings the loom to a total stop, we can turn back to the source of consciousness, “by nature, pure and bright.” If this is true, then the beauty of the morning star glimpsed by the Buddha wasn’t just a quality of the scene itself but also of the source behind it, shining through.

Ananda didn’t “fall” or commit a “sin” when a gorgeous streetwalker caught his eye, but he had yet to recognize the source as his own true identity—and Matangi’s, too. Indeed, the sutra later lets us know that even she, a former prostitute from the most disparaged caste, becomes enlightened and takes nuns’ vows. The sutra puts the matter this way:

[It’s] like a man pointing a finger at the moon to show it to others who should follow the direction of the finger to look at the moon. . . .If they look at the finger and mistake it for the moon, they lose [sight of] both. . . .

Until Ananda sees the “moon” at the core of his own mind, nothing he does can set him free, but once he stands face to face before the source, everything becomes “perfect and pure,” even a bordello. Reading these last words, we might want to step back from what looks like a moral abyss. If everything without exception is pure, then it would seem that we have the liberty to do whatever we please—even sleep with Matangi. Yet the sutra insists that returning to the source has the opposite effect. Viewing the world of form through the eyes of emptiness, we become aware of the suffering that we’ve been unable to confront thus far. This is why the sutra leads us step by step to a culminating encounter with the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara, whose name means “the one who hears the cries of sentient beings.”

Related: Beauty Beyond Beauty

In the west, beauty, truth and goodness went their separate ways centuries ago, and for the soundest of reasons. We’ve learned that standards of beauty can be used to isolate, diminish, or exclude those who can’t or won’t conform. And we’re hardly alone in this regard. People in ancient India and China devised standards as oppressive as anything in vogue in Paris or Milan. But some Buddhists also understood that only through the senses can we become aware of the existence of others. And only through the special beauty that arises when form and emptiness converge can we move beyond the boundaries of the self to see those others as inseparable from us. Once Ananda turns from the source to Matangi, she will become beautiful to him in the same way that the Buddha did.

It’s true that the dharma has at times proscribed sensuality or imposed various containments. But following the Shurangama’s lead, other Buddhists have used it to awaken. And they’ve done so believing that the radiance of Mind is always there, and that even our bonds become ornaments when we understand them as Mind-created, too, arising from the source like everything else. This acceptance of the senses may seem to take us far from the spirit of the suttas, but making distinctions between “pure” and “impure,” or between “clean” and “defiled,” closes us off when we need to connect. Maybe a koan can show us how:

As the [government] officer Lu Hsuan was talking with Nan Ch’uan, he said, “Master of the Teachings Chao said, ‘Heaven, earth, and I have the same root; myriad things and I are one body.’ This is quite marvelous.”

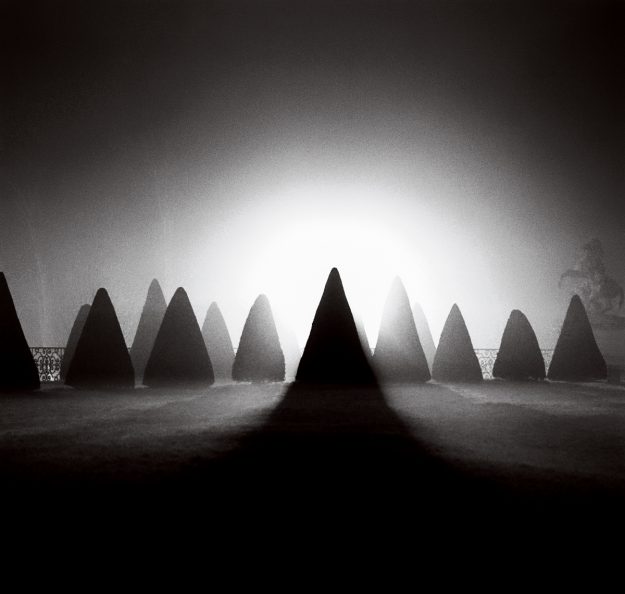

Nan Ch’uan pointed to a flower in the garden. He called to the officer and said, “People these days see this flower as in a dream.”

—The Blue Cliff Record, trans. Thomas Cleary and J. C. Cleary

Lu Hsuan has often heard Master Chao preach that everything has “the same root” and belongs to the same great body. Lu thinks he may know what these words mean, but he asks his friend Nan Ch’uan for guidance.

The world we take for granted arises through an artistry not our own from a place deeper than thought.

Predictably, Nan Ch’uan’s reply sets us up to reach the wrong conclusion: if we want to awaken, we’ll have to bring our dreaming to a stop. Then, supposedly, we can see things as they are. But in fact, the more we struggle to extract ourselves from appearances, the stronger the Kapila magic grows, along with our nagging sense of loneliness, so far are we from the “one body.” Renunciation just won’t work.

The world we take for granted—with its gardens and flowers—arises through an artistry not our own from a place deeper than thought. And we participate in that artistry when we recognize the visible as part of an invisible whole. There form and emptiness, as Zen tradition says, are like the matching halves of a broken coin joined together at last.

Because we aren’t buddhas most of the time, we’ll keep breaking that coin in two, but our work is constantly to embrace the other as the self.

Only in the dream we call everyday life can this work get done, and so liberation means discovering the dreamer behind the veil of consciousness. Before we’ve pulled that veil aside, we can describe the world in any way we please: as a heaven, a hell, or some condition in between. But when we’ve traced the senses back to the Mind’s intrinsic radiance, every experience becomes the path— beautiful in the beginning, the middle, and the end, just as the Buddha said.