When people take refuge in the formal ceremony of becoming a Buddhist, they receive a name that indicates how they should work. I’ve noticed that when people get the name “Renunciation,” they hate it. It makes them feel terrible; they feel as if someone gave them the name “Torture Chamber,” or perhaps “Torture Chamber of Enlightenment.” People usually don’t like the name “Discipline” either, but so much depends on how you look at these things. Renunciation does not have to be regarded as negative. I was taught that it has to do with letting go of holding back. What one is renouncing is closing down and shutting off from life. You could say that renunciation is the same thing as opening to the teachings of the present moment.

It’s probably good to think of the ground of renunciation as being our good old selves, our basic decency and sense of humor. In Buddhist teachings, as well as in the teachings of many other contemplative or mystical traditions, the basic view is that people are fundamentally good and healthy. It’s as if everyone who has ever been born has the same birthright, which is enormous potential of warm heart and clear mind. The ground of renunciation is realizing that we already have exactly what we need, that what we have already is good. Every moment of time has enormous energy in it, and we could connect with that.

I was recently in a doctor’s office that had a poster on the wall of an old native American woman walking along the road, holding the hand of a little child. The caption read: “The seasons come and go, summer follows spring and fall follows summer and winter follows fall, and human beings are born and mature, have their middle age, begin to grow older and die, and everything has its cycles. Day follows night, night follows day. It is good to be part of all of this.”

Related: The Fundamental Ambiguity of Being Human

Renunciation is realizing that our nostalgia for wanting to stay in a protected, limited, petty world is insane. Once you begin to get the feeling of how big the world is and how vast our potential for experiencing life is, then you really begin to understand renunciation. When we sit in meditation, we feel our breath as it goes out, and we have some sense of willingness just to be open to the present moment. Then our minds wander off into all kinds of stories and fabrications and manufactured realities, and we say to ourselves, “It’s thinking.” We say that with a lot of gentleness and a lot of precision. Every time we are willing to let the story line go, and every time we are willing to let go at the end of the out breath, that’s fundamental renunciation: learning how to let go of holding on and holding back.

The river flows rapidly down the mountain, and then all of a sudden it gets blocked with big boulders and a lot of trees. The water can’t go any further, even though it has tremendous force and forward energy. It just gets blocked there. That’s what happens with us, too; we get blocked like that. Letting go at the end of the out-breath, letting the thoughts go, is like moving one of those boulders away so that the water can keep flowing, so that our energy and our life force can keep evolving and going forward. We don’t, out of fear of the unknown, have to put up these blocks, these dams, that basically say no to life and to feeling life.

So renunciation is seeing clearly how we hold back, how we pull away, how we shut down, how we close off, and then learning how to open. It’s about saying yes to whatever is put on your plate, whatever knocks on your door, whatever calls you up on your telephone. How we actually do that has to do with coming up against our edge, which is actually the moment when we learn what renunciation means. There is a story about a group of people climbing to the top of a mountain. It turns out it’s pretty steep, and as soon as they get up to a certain height, a couple of people look down and see how far it is, and completely freeze; they had come up against their edge and they couldn’t go beyond it. Their fear was so great, they couldn’t move. Other people tripped on ahead, laughing and talking, but as the climb got steeper and more scary, more people began to get scared and freeze. All the way up this mountain there were places where people met their edge and just froze and couldn’t go any further. The moral of the story is that it really doesn’t make any difference where you meet your edge; just meeting it is the point. Life is a whole journey of meeting your edge again and again. That’s where you’re challenged; that’s where, if you’re a person who wants to live, you start to ask yourself questions like, “Now, why am I so scared? What is it that I don’t want to see? Why can’t I go any further than this?” The happy people who got to the top were not the heroes of the day. They just weren’t afraid of heights; they are going to meet their edge somewhere else. The ones who froze at the bottom were not the losers. They simply stopped first and so their lesson came earlier than the others. However, sooner or later, everybody meets his or her own edge.

When we meditate, we’re creating a situation in which there’s a lot of space. That sounds good but actually it can be unnerving, because when there’s a lot of space you can see very clearly: you’ve removed your veils, your shields, your armor, your dark glasses, your earplugs, your layers of mittens, your heavy boots. Finally you’re standing, touching the earth, feeling the sun on your body, feeling its brightness, hearing all the noises without anything to dull the sound. You take off your nose plug, and maybe you’re going to smell lovely fresh air or maybe you’re in the middle of a garbage dump. Since meditation has this quality of bringing you very close to yourself and your experience, you tend to come up against your edge faster. It’s not an edge that wasn’t there before, but because things are so simplified and clear, you see it, and you see it vividly and clearly.

How do we renounce? How do we work with this tendency to block and to freeze and to refuse to take another step toward the unknown? If our edge is like a huge stone wall with a door in it, how do we learn to open the door and step through it again and again, so that life becomes a process of growing up, becoming more and more fearless and flexible, more and more able to play like a raven in the wind?

Related: The Three Things We Fear Most

The animals and the plants here on Cape Breton are hardy and fearless and playful and joyful. The wilder the weather is, the more the ravens love it. They have the time of their lives in the winter, when the wind gets much stronger and there’s lots of ice and snow. They challenge the wind. They get up on the tops of the trees and hold on with their claws and then they grab on with their beaks as well. At some point they just let go into the wind and let it blow them away. Then they play on it, float in it. After a while, they’ll go back to the tree and start over. It’s a game. Once I saw them in an incredible hurricane-velocity wind, grabbing each other’s feet and dropping and then letting go and flying out. It was like a circus act. They have had to develop a zest for challenge and for life. As you can see, it adds up to tremendous beauty and inspiration. The same goes for us.

Whenever you realize you have met your edge, rather than think, “I have made a mistake,” you can acknowledge the present moment and its teaching. You can hear the message, which is simply that you’re saying, “No.” The instruction is to soften, to connect with your heart and engender a basic attitude of generosity and compassion toward yourself.

The journey of awakening—the classical journey of the mythical hero or heroine—is one of continually coming up against big challenges and then learning how to soften and open. In other words, the paralyzed quality seems to be hardening and refusing, and the letting go or the renunciation of that attitude is simply feeling the whole thing in your heart, letting it touch your heart. You soften and feel compassion for your predicament and for the whole human condition. You soften so that you can actually sit there with those troubling feelings and let them soften you more.

The whole journey of renunciation, or starting to say yes to life, is realizing first of all that you’ve come up against your edge, that everything in you is saying no, and then at that point, softening. This is yet another opportunity to develop loving-kindness for yourself, which results in playfulness—learning to play like a raven in the wind.

♦

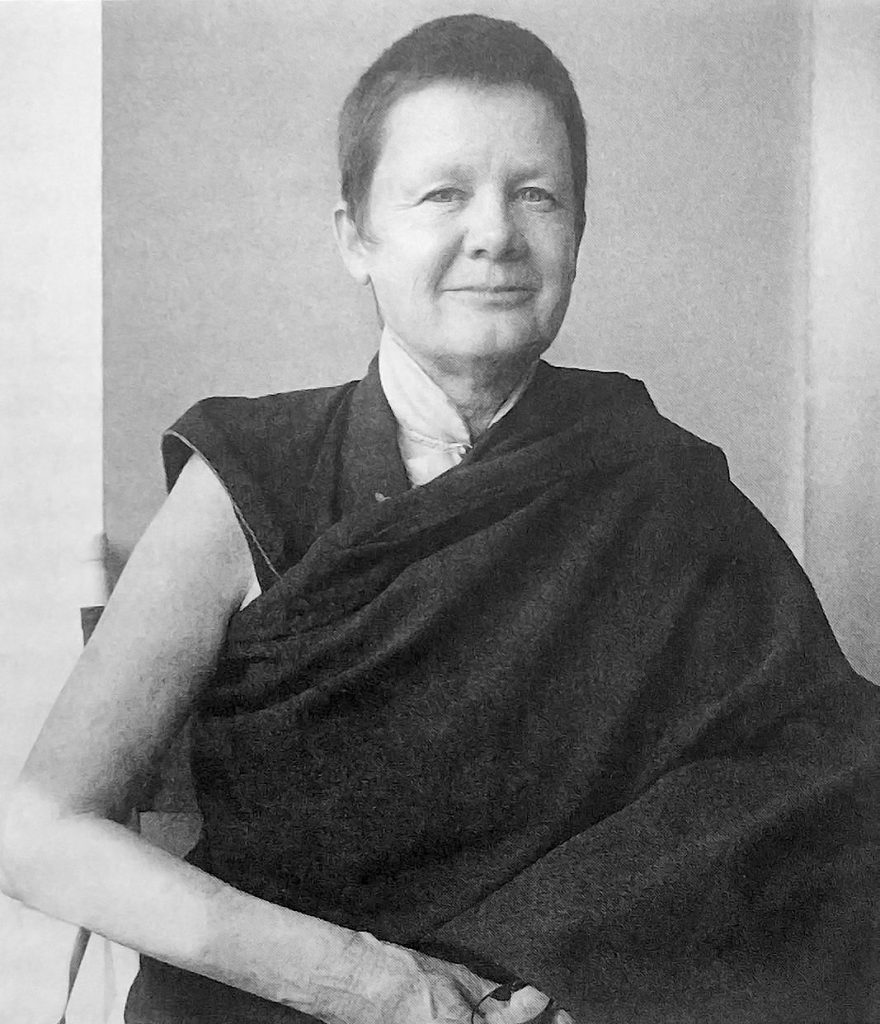

Pema Chödrön is an American nun in the Kagyu lineage of Tibetan Buddhism, and the director of Gampo Abbey, on Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, the first monastery in the Tibetan Vajrayana tradition in North America. After practicing for almost twenty years, she now represents one of the most respected examples of the transmission of Buddhist teachings to American disciples. Born Dierdre Blomfield-Brown, Pema graduated from the elite Miss Porter’s school and then attended Sarah Lawrence College and the University of California at Berkeley. At 21, she married and had two children. After a painful second divorce in 1972, she began looking for spiritual guidance, and soon became the student of the late Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. In 1974, she received the nun’s novice ordination from His Holiness Gyalwa Karmapa and, at his request, took the full nun’s ordination in Hong Kong in 1981. Like a Raven in the Wind was adapted from a talk given during a one-month practice period. A collection of Pema Chödrön’s talks, The Wisdom of No Escape, will be published this fall [1991] by Shambhala Publications.

Excerpted from The Places That Scare You © 2001 by Pema Chödrön. Reprinted by arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc., Boston.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.