Thailand’s King Vajiralongkorn (Rama X) recently invited four senior Western monks in the Thai Forest Tradition of Theravada Buddhism to receive royal titles in honor of their contribution to Buddhism in Thailand and around the world. While the event was part of a long-standing tradition, it also marked a new development for Buddhism in the country.

Thai Forest monks historically have disregarded social status and systems authority, preferring to focus on meditation practices in remote forests and caves, as the Buddha and his disciples once did. Yet despite its often-secluded practices, the Thai Forest Tradition has had a tremendous impact since its beginnings at the turn of the 20th century. The school’s dedication to meditation, commitment to renunciation, and lack of emphasis on ritual and ceremony held great appeal for Buddhists in the West, where disciples have established hundreds of Thai Forest monasteries.

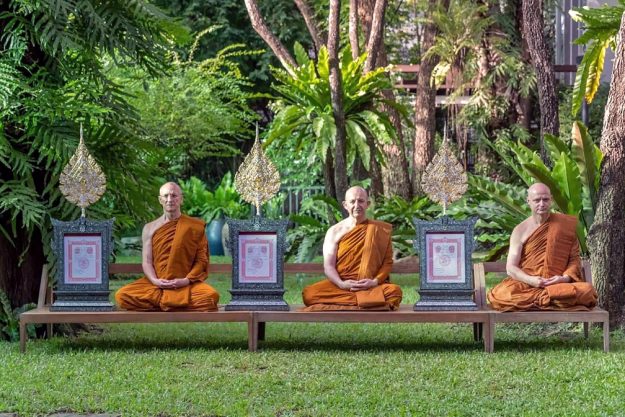

In honor of the Western teachers’ contributions to the proliferation of Thai culture, the king invited the monks to receive the royal titles on July 28 as part of his birthday celebration. The invitees were Ajahn Sumedho, the retired abbot of Amaravati Buddhist Monastery in southeastern England (Sumedho was not able to attend); Ajahn Amaro, the current abbot of Amaravati; Ajahn Jayasaro, an author and teacher who lives in a hermitage near Khao Yai Mountain, about two hours outside Bangkok; and Ajahn Pasanno, former abbot and guiding elder of Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery in Redwood Valley, California.

To better understand the significance of this event, Tricycle spoke with Ajahn Pasanno about the title he received, Chao Khun, its history, and what it means for his tradition in Thailand and the West.

How would you describe the Chao Khun title in Thai Buddhism?

It’s an honor and a title, but it’s also an acknowledgment of both respect and the contribution that one has made. The meaning comes from ancient times; Chao Khun was actually a royal title, but after Thailand became a constitutional monarchy, the title came to be applied more broadly. It’s considered a big deal, like the honors from the Queen of England in Commonwealth countries.

This was the first time that the new King of Thailand had done this since his father passed away [in October 2016]. In his first act of bestowing these titles, he invited four Western monks from the Thai Forest Tradition. It seems that he wanted to acknowledge the Western Buddhist pioneers of the tradition, particularly the students of Ajahn Chah.

As someone who trained in Thailand and now teaches in the US, what does this title mean to you?

It helps to have this “bridge” between the two different cultures. I hope that being acknowledged in this way will allow me to provide an example, so that the presence of the Thai Forest Tradition in the West won’t be seen as an oddity or an outlier. It’s an acknowledgement that being from a different background and establishing places of Buddhist practice in the West is a valuable and worthwhile pursuit.

Thailand is very much a part of the modern world. As they are being modernized and influenced by the international community, traditional structures and religion are losing their relevance. This event draws attention to the significance of the Thai Forest Tradition in the West, and that’s meaningful for Thailand as well. The Thai Forest Tradition isn’t even mainstream in Thailand. Many Western practitioners don’t realize that.

Related: How a Forest Monastery Took Root in British Columbia

What is the relationship between the Thai royalty and the Thai Forest Tradition?

These titles from the king are normally given only to monastics in the administrative and scholastic fields. It’s somewhat rare for the Forest monks to receive this acknowledgement because we consciously try to stay out of the loop of formal recognition and focus on practice. One of the long-standing tenets of the Forest Tradition is to try to distance oneself from the power structures so that we can be more available to practice and teach.

Would you say that state support for a religion can be a double-edged sword?

It’s something that we have to be very conscious of. If you’re too close to the power structures, it’s easy to get drawn in, but if you do have some foothold, it can give you the opportunity to affect those structures. There’s a bit of a dance going on, and you’re never quite sure of the steps.

You were the abbot of Abhayagiri Monastery in California until you stepped back recently to take more time to practice. That seems very fitting with the Thai Forest Tradition’s history of retreating from society to practice.

As a Buddhist monk, and particularly as a monk in the West, I’m not just concerned about what I say. It’s important for me to be a steady and consistent example of that which is peaceful and compassionate. This is my 46th year as a monk. Firstly, I’m here to practice. But I’m also here to be an example and give encouragement and support to both the monastic and lay community.

What do you hope for the Thai Forest Tradition as it continues to grow in the West?

Buddhism in the West is still so new. I think it’s helpful to get a fuller picture of it as a tradition, a religion, and a part of culture and history as it is in Thailand. Looking at traditional Buddhism in another country is helpful to expand our perspective and have the example of what’s useful and helpful. But it’s also important to understand what’s unhelpful and not useful to carry into the West. We need to remember the differences between the cultural aspects of Buddhism and the fundamental teachings of the Buddha.