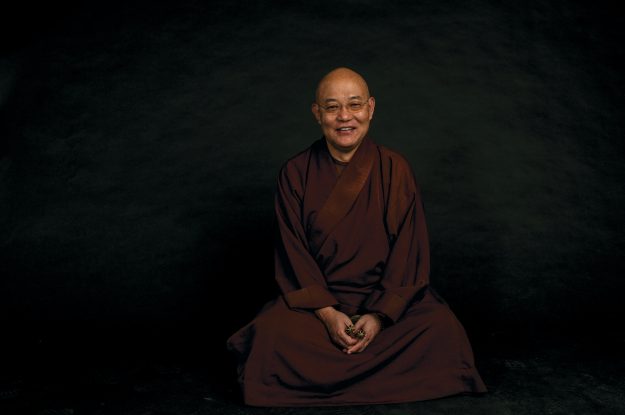

Artist and Buddhist teacher Losang Samten was born in Tibet in 1953. In 1959, following Communist China’s occupation of Tibet, his family fled to Nepal. They eventually resettled in India, where Samten later entered Namgyal monastery. After receiving the degree of geshe in 1985, he served as personal attendant to His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama before moving to New York City in 1988. He has been making sand mandalas at institutions across the United States for more than 30 years. In March, Anne Doran and Tricycle contributing editor Frank Olinsky sat down with him to talk about his work.

When did you learn to make sand mandalas? In 1969, I was one of a group of young monks selected to train in traditional Tibetan religious rituals at Namgyal Monastery, His Holiness’s monastery in Dharamsala, India. The older generation was dying, and there was an urgency around preserving the culture. We were taught ritual dance, ritual music, butter sculpture making—everything. And for four summers starting around 1970, some of us learned to make sand mandalas.

How did you end up making sand mandalas in America? In the late 1980s, Barry Bryant, who was then director of the Samaya Foundation [an organization dedicated to educating people about Tibetan culture], asked His Holiness about having a sand mandala made at the foundation’s center in downtown Manhattan. Up until then, sand mandalas were constructed only for religious ceremonies, like the Kalachakra empowerments His Holiness gave in India. So for a while, His Holiness couldn’t decide what to say. Finally, he agreed to send one monk over. He asked me if I wanted to go and I said yes. I came to New York in February 1988 and made a Guhyasamaja [a tantric deity] sand mandala at Barry’s foundation.

Later that year, Malcolm Arth, the head of the American Museum of Natural History’s education department, asked me to make a mandala for the museum. It was the first time a mandala would ever be produced for public view in the United States.

Related: Tantric Art: Maps of Enlightenment

It was a Kalachakra [a system of Tantric teachings] mandala, right? Right. People could come and watch it being made. I worked on it every day for six weeks, and viewers could ask me questions. We had 50,000 visitors.

His Holiness told me he thought I should stay longer in America. So I stayed and kept making mandalas, sometimes by myself, sometimes with other monks. We’d make Kalachakra mandalas, mandalas of compassion, all of that. But always, in the back of my mind, I’d be thinking that they were very complicated to explain.

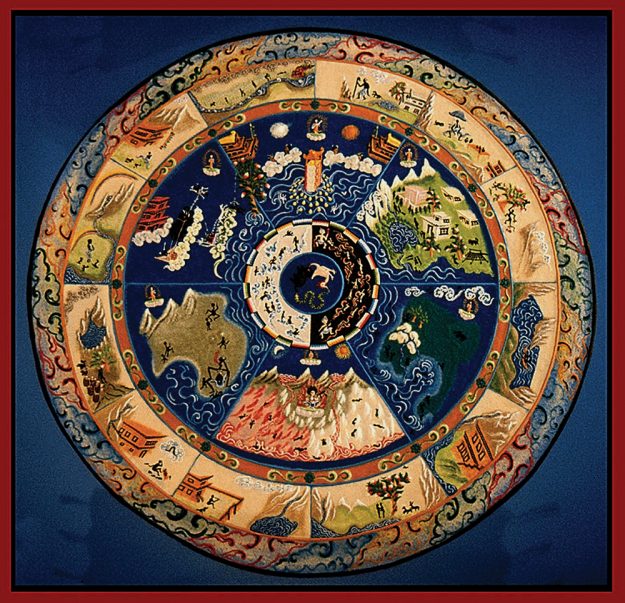

Generally speaking, you’re not supposed to share the Kalachakra mandala unless the viewer has had the correct ritual empowerment. Even now, some of the more sensitive monks and nuns believe it’s bad to give those teachings in public. I wondered what might be a mandala that people could relate to, and I thought, the Wheel of Life, because it has all the basic tenets of Buddhism contained within it.

The Wheel of Life is not a traditional sand mandala motif, though. Right. It’s a very ancient motif, but always for thangkas [Tibetan scroll paintings], never for sand.

So there was no precedent for it. No, there was no model for it. I’d never done a Wheel of Life sand mandala. But I’d been thinking about doing one. And then, in 1998, I got an invitation from the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno.

Perfect. The roulette wheel of life. I asked His Holiness if it was OK to make a Wheel of Life in sand, even though it wasn’t a traditional design. He thought it was a perfect way to introduce people to Buddhism. Since then I’ve done it in many places.

Do you talk about the imagery with viewers as you create the mandalas? Absolutely. The whole idea is to have a conversation. At the center of the Wheel of Life are the three poisons: attachment (or greed), anger, and ignorance, symbolized by the rooster, the snake, and the pig, respectively. When I make a Wheel of Life, I’ll talk about the four noble truths—suffering, the causes of suffering, the end of suffering, and the path to the end of suffering. And I’ll talk about how suffering is caused by greed, anger, and ignorance. Not one person has ever said to me, “That isn’t true.” It makes perfect sense to everybody, Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike.

And what about the other elements in the mandala? The animals at the center are surrounded by the six realms of existence, and the six realms are surrounded by the twelve dependent originations, right? Right. So then we talk about the law of karma and about interdependence.

“I’ll talk about how suffering is caused by greed, anger, and ignorance. Not one person has ever said to me, ‘That isn’t true.'”

Even though the Wheel of Life is not typically made in sand, it’s still a traditional image. Within that traditional structure, though, you get pretty imaginative. Is that where you get to be an artist? Exactly. A Kalachakra mandala in New York, a Kalachakra mandala in Los Angeles, and a Kalachakra mandala in Chicago are all pretty much the same. But a Wheel of Life mandala in Reno, a Wheel of Life mandala in Philadelphia, a Wheel of Life mandala in New York—each one I make a little differently. For instance, when I made a Wheel of Life for the Philadelphia Cathedral, I put the cathedral in it. And where traditionally the six realms each have an image of the Buddha, I put in Jesus. That doesn’t go against any Buddhist tradition at all.

As a master of ritual dance—which you also studied in Tibet—do you find adapting traditional teachings to Western audiences a kind of dance in itself? My audiences are incredibly varied. Many people who come to see my mandalas have never heard of Tibet or of Buddhism, but they do understand what’s gone wrong in their lives as a result of anger, ignorance, or greed. So there’s always a chance to communicate. At first, some people aren’t comfortable asking questions. But they come back the next day, and the next, and then they will ask me to tell them more.

Related: The Moving Mandala: Inside Bhutan’s Sacred Dance Festivals

I imagine when you dismantle the mandala, people often ask how you can destroy something so beautiful. Yes. So I make a dance with them. On the first day, someone asks me to tell them more. On the second or third day, they might ask how I’m going to preserve it, and I’ll say, “Well, next Friday we are going to dismantle it.” And they’ll be shocked. That’s when I, or one of the other ritual artists, will talk about impermanence.

Do you think there’s a particular reason why the Wheel of Life, with its lesson in interdependence, is so important right now? Absolutely. The illusion that we are not interdependent is really the cause of most of our problems today. In the last year or so, I’ve been watching more news than at any other time in my life. I say to myself, “I will only watch this much and then go do my prayers,” but then I have to keep watching.

But I also tell myself that I have to participate. I’m living in this time and in this place. In Tibet, we lost our country because we didn’t pay attention to what was happening. And it matters what happens in the United States. This country is very important for many people in the world. Even though they had to leave their home in 1959, my parents felt that all was not lost. Why? Because America was still there. In 1963, when JFK was assassinated, I remember Tibetans were so disturbed by the news. Even now people look to America for hope. And so, if America falls apart, who do they look to? I tell my younger students, “You need to pay attention to what is going on. You should never think that you can’t make a difference in this world. You can. That is very, very important to understand.”