In Kathmandu’s tourist district of Thamel sits a planned outdoor shopping area called Mandala Street. Nearly every morning—around when the foreigner-friendly coffee shop Himalayan Java opens its doors—a man blows his conch shell loudly from a second-story walkway. He typically wears flowing white robes and a large turban with a peacock feather stuck in its folds, and sports a beard and mustache curled into near-perfect circles. He is a self-described “sound-bowl healer” who offers to align chakras with specially tuned metal bowls, a technique, he will tell you, that is practiced by an ancient lineage of yogis. The staff of Himalayan Java are suspicious of his sound bowl healings, but some of the visitors are spellbound by him, the picture of the Orientalized South Asian holy man, and a few find their way to his healing table each day during the peak tourist seasons.

These sound bowls, or “Tibetan singing bowls” as they are frequently called, have become nearly ubiquitous in Buddhist contexts in North America and Europe. They are used in mindfulness practices, yoga studios, and even some newer Buddhist rituals, yet a credible consensus regarding their origins is difficult to find. There is no hard evidence that the sound bowls are ancient—and even less that they are Tibetan.

The dubious claims of the bowls’ Tibetan origins have not escaped the notice of the Tibetan community in North America. A handful of blog entries by Tibetan writers in North America have appeared questioning the pedigree of the allegedly “Tibetan” bowls, and as recently as February 18, an op-ed piece by Tenzin Dheden of the Canada Tibet Committee ran in the Toronto Star entitled “‘Tibetan singing bowls’ are not Tibetan. Sincerely, a Tibetan person.” The piece garnered attention on Facebook with one commenter noting, “I’ve always wondered why Injis [foreigners/non-Tibetans] are so fond of these bowls. In the past, I’ve asked a number of Tibetans, including monks, and none of them had heard about [them].”

I spoke to a few other Tibetan scholars/friends and colleagues, and they said they had similar experiences. One Geluk monk and geshe currently in the United States pursuing a graduate degree when asked whether or not he had encountered the bowls while growing up in Kham or during his monastic training in Mysore, said: “When I was in Tibet, I never saw those bowls that you hit and spin around the rim. I saw them in India . . . But in India there are many different things.”

So if Tibetan singing bowls are not a Tibetan creation, what are they? And where did they come from?

The bowls’ popularity, as well as their reputation for healing through vibrations, surged in the early 1990s. Around the same time, international interest in Tibet increased, and the bowls’ supposed origins in the Land of Snows granted them a mystique and material value they otherwise might not have possessed. Today, sound bowl healing shops are common in the Kathmandu Valley, with locations in Patan, Freak Street, and Bhaktapur in addition to Thamel, where merchants tell potential customers that their bowls originated in Tibet, the Himalayas, or both, and are part of an ancient tradition.

The production of these sound bowls—often inscribed with an image of the Buddha and/or Tibetan script (commonly the six-syllable mantra Om mani padme hum)—is not limited to Nepal. They may be found in tourist areas throughout South and Southeast Asia and in specialty shops in the Americas and Europe, as well as online.

At the close of 2019, there were “over 10,000” results in an Amazon.com search for “Tibetan singing bowls.” One top-seller had over 2,000 reviews; another had more than 1,000. They are used in mindfulness settings, spas, yoga studios, and even as reminder chimes on cell phones. One might expect something so popular could be easily traced, but the trail quickly goes cold.

Several books dedicated to the subject of using sound bowls for healing have been published since the early 1990s. Their opening pages offer a wide variety of origin stories, attributing them to “tantric shamans,” “shamanic lamas,” “the Zen of Tibet,” “spirit helpers,” “pre-Buddhist Bon faith,” and “ngakpas,” a type of empowered, non-monastic practitioner. The bowls are said to date back to the time of Shakyamuni Buddha, but have been hidden as a “native” secret. Some claim the sound bowls were part of an oral tradition that only became exposed when the Chinese army invaded in the 1950s.

While these origin myths vary, they share a number of themes. The stories are shrouded in mystery and secrecy; are transmitted orally and therefore lack a written record; invoke the supernatural, and spirits are sometimes involved; often are attributed to groups, such as Bon or ngakpa, who are considered fringe and have a reputation for being misunderstood; and only recently became available after being displaced from their traditional context.

All of which fits in with the way inaccurate portrayals of Tibet that have proliferated for decades. As the scholar Donald Lopez, Jr., wrote in his Prisoners of Shangri-La, Tibet is depicted as being “from an eternal classical age, set high in a Himalayan keep outside time and history” and “embodies the spiritual and ancient.”

Variations of the sound bowl origin myths have found their way into publications as prestigious as the Guardian and the Oxford Handbook of Medical Ethnomusicology. Neither provides citation, but instead presents the information as general knowledge—namely, that something “Tibetan” is necessarily ancient and esoteric. Several themes of the Orientalized Tibet are found in the Medical Ethnomusicology reference work—“ancient,” “remarkable,” “unexplainable” from Western science.

But the true origin of the “Tibetan singing bowls” may only date back to the 1970s.

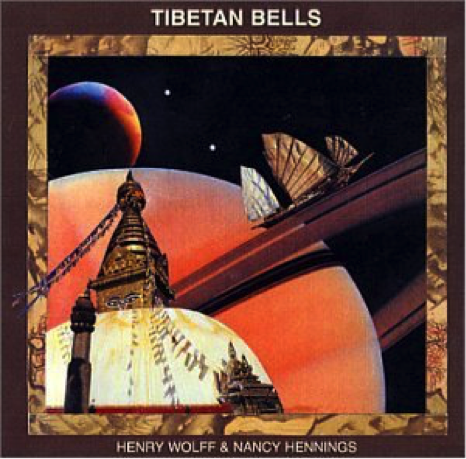

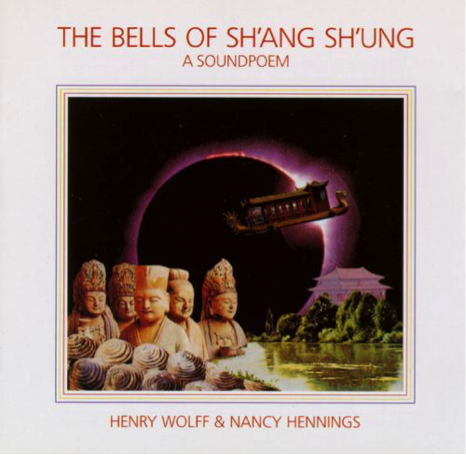

Sound bowls first appeared in the written record in 1972, when the American musicians Nancy Hennings and Henry Wolff released their album Tibetan Bells. The New Age album used an array of percussion instruments to generate minimalist soundscapes of various long-held tones. Tibetan Bells and the 1978 follow-up Tibetan Bells II were intended to generate an experience in the listener similar to a psychedelic trip. They also released a Tibetan Bells III (1988), Tibetan Bells IV: The Bells of Sh’ang Sh’ung (1991), and a collaborative album with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart entitled Yamantaka (1982) after the tantric Buddhist deity personifying the conquest of death. The cover art for Tibetan Bells depicts a Chinese junk sailing vessel ascending Saturn’s rings as it moves away from a Buddhist stupa. In the liner notes of the album Wolff explains that the music of Tibetan Bells II “charts the progress of an individual soul or spirit as it proceeds through the last recognizable phases of existence.” Referring to the minimalist nature of Yamantaka, Hart stated in a 1983 interview, “We’re so inundated by Western music and our own sounds that sometimes we can’t hear the purity of other music.”

As Hennings and Wolff continued to produce albums using “Tibetan” instrumentation, the narrative of a mystical psychedelic trip only increased in its complexity—and several Orientalist stereotypes of the “mystical East” are invoked while traces of a number of traditions are flattened into one. The liner notes of The Bells of Sh’ang Sh’ung read: “Sh’ang Sh’ung is the Tibetan name for the mythic lost kingdom where, it is said, the most precious teachings of Buddhism were conceived, are concealed, and remain preserved to this day . . . The Eastern mind, this remote and lost terrain—where fact or fancy—occupies a position similar to that of the Castle of the Holy Grail, for example, in the roots of the Western subconscious.” The cover of the album includes a grouping of Chinese statues of bodhisattvas in the foreground, behind which a Chinese lake vessel appears to be sailing past a solar eclipse at its peak.

A 1985 review of the album in Yoga Journal entitled “Visionary Music for These Times of Transition” tells us Tibetan Bells and Tibetan Bells II “brought a wide grouping of Central Asian and Tibetan instruments into Western consciousness for the first time. They have always been in search of recording technology that could truly capture the subtleties and wide-ranging sound qualities so characteristic of Tibetan instruments.”

But the primary musical instrument used in their work—the sound bowl—cannot be conclusively demonstrated to come from Tibet.

There is a long tradition of using musical instruments in religious life in Tibet. These instruments have been comprehensively catalogued by scholars, as have many of the rituals in which they appear. In his pioneering Tibetan Ritual Music: A General Survey with Special Reference to the Mindroling Tradition, Daniel A. Scheidegger catalogs 12 major instruments and 36 minor variations. Several of these are bells and chimes; none of the instruments catalogued are sound bowls, or anything which could become or be mistaken with a “bowl” shape.

There is, however, a class of bowls in Japan called rin that, when struck with a wooden stick, produce a sound reminiscent of the mass-marketed Tibetan singing bowls. Rin are also kept on a small cushion similar to the one which is associated with Tibetan bowls, and the traditional wooden striker is often covered in a felt tip, identical to the kind sold with Tibetan singing bowls. A Google image search for “rin” will result in a mix of sound bowls variously labeled “Tibetan singing bowls” or “rin singing bowls.”

Perhaps Hennings and Wolff acquired a rin and mistakenly labeled it as Tibetan? Or perhaps they were incorrectly told it was Tibetan? Regardless, it appears that neither they nor their fans sought to verify this claim, instead capitalizing on the power that the word Tibet has to conjure up the image of a far-off, mysterious land of magic and mysticism—a power that was particularly relevant to their time.

Tibetan Bells was released following the countercultural revolutions of the sixties and offers the kind of spiritual transformation through sound that was promised by Timothy Leary and his message of using LSD to “tune in, turn on, drop out.” Leary himself, together with his colleagues in the Harvard psychology department Richard Alpert (later Ram Dass) and Robert Metzger, released their own work on spiritual transformation, drawing on Orientalized fantasies of Tibet in their 1963 book The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. The second incarnation in the modern West after Walter Evans-Wentz’s pioneering 1927 translation of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Leary, et al., drew from the now-famous Tibetan Nyingma text to draw analogies between the states between (bardo), embodied lives, and the experience of an LSD trip. Treating the psychedelic journey as a vision quest, Leary and his cohorts stress the analogs of ego death, altered and vivid perceptions, and visions of a bright light. By taking LSD a person can apparently achieve Buddhism’s ultimate goal. (The authors even state that “now, for the first time, we possess the means of providing enlightenment to any prepared volunteer.”)

Tibetan Bells is a new interpretation of this aged paradigm. Hennings and Wolff arranged their album to illustrate a psychedelic trip of transformation through sound that both mimics and leads up to the experience described in the traditional text. Perhaps they labeled their instruments “Tibetan”—or accepted that label—for the cultural weight it carried, playing off of the same myth that inspired Helena Blavatsky’s theosophical musings, Evans-Wentz’s “Book of the Dead,” and Leary, Alpert and Metzger’s trips, and Hennings and Wolff’s own music.

While the popularity of the idea that psychedelics can awake a purity of consciousness has faded, the quest for “the means of providing enlightenment to any prepared volunteer” continues, where it has always taken place—Tibet. “Tibetan singing bowls” have become a commodified version of Tibetan spirituality, easily packaged, sold, and distributed in a global, online market. The idea that the sound bowl vibrations can effortlessly bring about some kind of spiritual transformation reinforces the flattening of centuries of tradition into a single and easily-accessible trip or sound.

Many things have changed since Tibetan Bells. The means of production of Tibetan spirituality have shifted from established traditions to merchants in tourist bazaars to, finally, Amazon.com. The sound bowl is the perfect spiritual device in today’s fast-paced, quick-fix marketplace where everything is only a click away—the bowl is small, easy-to-use, exotic, guaranteed to bring tranquility, and de-stressing. But this stress relief comes at a price. As Tenzin Dheden writes in the Toronto Star:

In the Western imagination, Tibetan identity/brand is largely confined to a mythical, asexual, masculine spiritual figure. . . The real Tibet is subservient to the myth of Tibet. This myth, however, has real power and it has become the dominant framework through which the West perceives Tibetan political struggle. The myth reduces Tibet to a museum exhibit. The myth conflates the politics of Tibet to a question of the survival of a dying, one-dimensional civilization. The myth prevents Tibet’s political concerns from being taken seriously. The myth invites sentimentalities rather than political expediency. The myth ensures Tibetans never get the institutional and governmental support we tirelessly lobby for.

Like the way the sound the bowls produced was in the Tibetan Bells albums, the exact origin of these devices remains a mystery. Who can say if they really have the power to heal? But even if they do, it seems that Tibet has nothing to do with it.