Achaan Runjuan levels her wise gaze as I ask yet another question. We are seated on benches at the windows of her kuti (cottage) in the wooded confines of Suan Mokkh, a Theravada Buddhist monastery in southern Thailand. From the monastery entrance comes the sound of dogs fighting, one animal screaming as the others maul it, while a drone of deep male voices chanting Pali verses comes from somewhere among the trees. The mae jis—modest, white-robed, shaven-headed women—are giggling together or pacing slowly in walking meditation. Orange-robed monks disappear into the jungle to their huts tucked among the tangled vines.

Achaan Runjuan’s two-story white stucco cottage stands a little apart from the other women’s dwellings, inside a wooden fence with bells on the gate. There are orchids planted around the large tree in her yard. Achaan means “teacher,” and the very fact that she bears this title sets her apart.

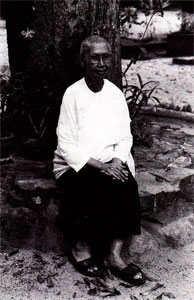

A woman in her seventies, Runjuan has smooth brown skin and a shadow of gray hair on her shaved head. When she is serious, her eyes hold steady; her strong mouth and jaw suggest the determination that led her to abandon a distinguished career in the secular world and “go forth into the homeless life,” as entry on the Theravada monastic path is called.

The heat holds me in a heavy damp embrace. Recognizing my discomfort, Runjuan picks up a bundle of palm fronds and begins to fan me. I’m disconcerted—shouldn’t I be fanning her? But she does it so matter-of-factly that I relax, glad for the modest agitation of the monsoon air.

Even though she is a busy woman, Achaan Runjuan gives the impression of ease, moving deliberately as she goes to her small kitchen area to get me a glass of water. Nothing in her manner suggests how extraordinary she is. Her role as a dhamma (dharma in Sanskrit) teacher, leading retreats for both Westerners and Thais here at Suan Mokkh, does not seem unusual from a Western perspective. After all, for almost forty years she worked in the Thai Department of Secondary Education where, among other things, she launched a successful national campaign to develop libraries in schools and establish library science departments in universities. It seems logical enough that, having entered religious life, she would assume a position of authority.

But this is Thailand, where an elephant’s walk illustrates the position of women in society. The animal’s back leg comes up and hits its front leg, pushing it forward. Thai men are the front legs of the elephant; Thai women are behind.

Early Indian and Chinese influences shaped these attitudes toward women. Indian Brahmanic social and religious values took root in early Thai culture, and the Brahmanic “Laws of Manu” denied women access to education, restricting them to domestic life. Traditional Chinese cultural values have also colored Thai society, enforcing the conception of women as malleable, petty, and intellectually inferior.

“In Thailand, men generally have an exploitative attitude towards women,” writes Chatsumarn Kabilsingh in Thai Women in Buddhism. “Women born into such a gender-stereotyped society will tend to internalize these beliefs and accept them as valid. Commonly held prejudices of women’s mental and physical inferiority, handed down through cultural tradition and sanctioned by religion, have profoundly affected Thai women’s self-image and expressions of self-worth.”

Given this societal context, it is not surprising that Thai women in institutionalized Buddhism have been marginalized. While there were thriving bhikkhuni sanghas (orders of nuns) in India, Sri Lanka, and other Asian countries, the Thais never ordained women. Thus, in the seven hundred years of Buddhism’s existence as the dominant religion in Thailand there has never been a fully recognized Thai nun. A few women have challenged this injustice by journeying to Taiwan or Hong Kong to be ordained, but Thai monks do not recognize their status when they return.

Although approximately ten thousand mae jis lead a religious life in Thailand, they are viewed by society as religious nonentities unworthy of alms. In the official bureaucracy of the Thai Department of Religious Affairs the mae jis do not exist; according to Chatsumarn Kabilsingh, its annual report includes detailed records on everyone involved with Thai temples—monks, novices, even temple boys—yet it makes no mention of the mae jis.

The majority of mae jis are uneducated village women, barred from teachings in monasteries, who struggle to survive on meager resources. Alienated from their society, mae jis are viewed as misfits fleeing social failure or misfortune. And although the Institute of Thai Mae Jis was organized in 1969, this body, and its supporting foundation, have only begun to effect substantial changes in the nuns’ status and material well-being. But even with all the odds stacked against them, a few women achieve the impossible, and Achaan Runjuan’s status as a highly respected teacher attests to this.

Runjuan is distinguished, as well, by her costume—black skirt and white blouse—and by living essentially as the male achaans do, protected by a fence and attended in her kuti by a young assistant. One of her most important teachers, she tells me, was a “lady master” who dressed this way. “Because I admired the lady master so much, I told myself that I would lead this kind of life, dress like her, and wear black and white.” Runjuan insists that she has no intention of separating herself from the mae jis. “If I were to change this black skirt for a white one, I would be a mae ji immediately because I follow the same precepts that the mae ji does. But I have no desire to ordain as a mae ji or anything else. It is more important to ordain in the heart than to ordain by the uniform.”

Born in Bangkok, Runjuan received a degree in a teachers’ college and then taught high school. Subsequently, she won a fellowship to the United States, where she spent the mid-fifties at the State University of Florida at Tallahassee earning a degree in education and library science. Back in Thailand, she began her career in the Department of Secondary Education.

“I was born into a Buddhist family, and so I was, you might say, a ‘registered Buddhist,’ like some ‘registered Christians.'” Religious practice included listening to temple sermons, taking precepts, practicing dana (generosity). She says, “I was brought up not to hurt and harm other people, but no one taught me not to hurt and harm myself. This is what real dhamma practice teaches.”

Runjuan never married, but she raised her nephew after his parents had divorced. During his third year of college, this young man had a nervous breakdown. Runjuan, who was teaching at the university and carrying a heavy professional load at the time, drove to the hospital every day to care for him. And after his recovery, he came to stay at her house.

“That was a terrible year for me,” says Runjuan explaining that it was this experience that turned her toward dhamma: “That was really dukkha (suffering). And I suffered much because of my attachment because he was my nephew and I had brought him up the best way I could and then this happened. I began to see that the success I had with my job and with other things in my life did not soothe this suffering at all.” Then, on a trip to the northeast for a weekend, she stayed in a forest monastery on the Mekong River, near the Laos border. That night the abbot gave the teaching that one needs to cultivate the mind when dukkha arises; he said one must not just be a good Buddhist from the outside but learn to do something for oneself from the inside.

Runjuan began to meditate and to go on regular trips to the monastery. But eventually she realized that she was clinging to the meditation and to the master, and that this was only another kind of attachment. Deciding never to return to this monastery, she continued meditating, and found another teacher, a laywoman named Kee. After her parents’ death, Kee had gone into the forest to meditate and cultivate mastery over the discursive mind. When Runjuan came to her, Kee was past seventy and blind, with sixty female disciples living with her; inspired by Kee’s example, Runjuan resolved to enter religious life.

“During that time I was still working, but I began to be more and more convinced by dhamma practice. My nephew had recovered and lived with his parents again. I didn’t have to care for anybody. I felt very free.”

Taking early retirement, Runjuan entered the religious life at the age of fifty-nine, shaving her head and wearing the costume of her “lady master.” Since Kee had died by then, Runjuan went to study with the renowned Buddhist master Achaan Cha, but soon after she arrived, he developed a brain tumor and was unable to teach. Viewing this as a lesson in anicca (the impermanence of all phenomena), she set off to find another teacher.

“As a woman, it’s very difficult,” Runjuan tells me. “If I were a man, it would have been easy to go anywhere because there are thousands of monasteries; but as a woman—and I meant to be a woman practitioner and not just use the monastery as shelter—I could not go many places.” (In Thailand, some aging women enter monasteries to live out their lives in a peaceful, secluded environment.) “But I needed a teacher,” she explains. “I knew I must go from monastery to monastery to search for one. And that I must walk alone, as awoman in Thai culture. I was not afraid because I was very established in the dhamma.”

Suan Mokkh, distinguished from ordinary Thai monasteries by its teacher, the great Buddhist scholar Achaan Buddhadasa, was one of the places Runjuan chose to investigate. With numerous books to his credit and a reputation for progressive views, Buddhadasa is well known for his ecumenical understanding. Rather than promoting formal meditation techniques, he encourages the Buddha’s teachings to be lived out in daily life.

Through books and tapes, Runjuan had heard Buddhadasa’s claim that when properly cultivated, meditation-in-action—what he terms a “naturally occurring concentration”—can awaken full liberation. But she journeyed to Suan Mokkh to observe whether he actually lived the practice he espoused. “After some time there,” she says, “I was convinced that whatever he taught, he practiced—that’s why I believed he could be my teacher.”

When Buddhadasa asked her to begin teaching dhamma, Runjuan refused, protesting that on the one hand, she had not studied sufficiently, and on the other, she had done enough teaching in her life and wanted to pursue her own path to liberation. But eventually she began to give talks to Westerners and Thais in retreats and took on the responsibilities of a teacher. She smiles, resigned, “That is how life is.”

Runjuan has picked up the palm-frond fan again and moves it slowly up and down as she continues, “When I put Buddhadasa’s teachings into practice, I saw that they work. Through this practice I began to lessen my clinging to what has caused dukkha for me. I began to see things as they are, not as I would like them to be, and the suffering in the mind became less and less.” As she stops to think, the fan flutters to rest on her black skirt. “I’m not enlightened,” she says, looking squarely at me, “but I know I am walking on the right path.”