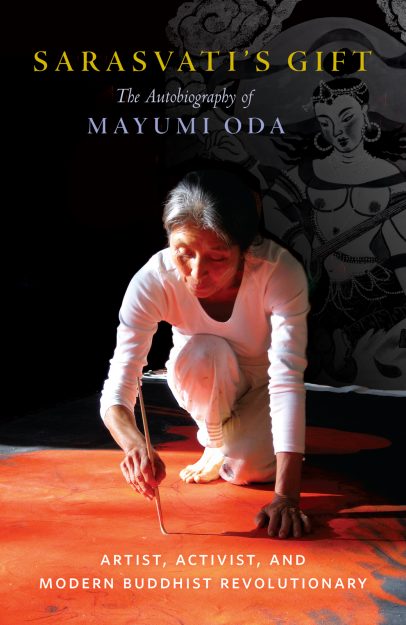

Artist and activist Mayumi Oda will be 80 years old in June, but it is she who drops a gift into our laps this year with the release of her autobiography, Sarasvati’s Gift. While Oda’s two earlier books could also be considered autobiographical (Goddesses from 1981 and I Opened the Gate, Laughing: An Inner Journey from 2002), neither gave us the thoroughly textured story of a life—devastating and inspiring, delightful and wrenching—that this book, bearing the name of the Hindu goddess of art, music, and wisdom, offers, along with family album photographs and Oda’s Tibetan thangka-inspired banners, never before collected in print.

by Mayumi Oda

Shambhala Publications, Nov. 2020 $22.95, 160 pp., paper

The life story Oda weaves for us is shaped by two nuclear disasters: the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan in 1945 and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011. Born in Tokyo, Japan, four years before the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oda describes experiences from her youth of hunger, deprivation, and loss that would inform every subsequent stage in her life, from artist to feminist and antinuclear activist. Her origins left scars that coexist with a backdrop of family life, sincere Buddhist practice, and hands-in-the-dirt devotion to the protection of the earth.

At the start, Oda takes us back to a childhood with loving parents who were forced to navigate the horrors of war, scraping together what food they could to provide for Mayumi and her two siblings until the firebombing of Tokyo forced them to flee to the countryside. Oda’s writing, a telling of the bombing’s aftermath when relatives ran through a bloody sea trying not to step on bodies, conveys the grim reality behind the art. “My earliest memories are of tremendous anxiety,” she writes before showing us Dakini the Sky Walker, poised on one leg and surrounded by raging fire, grasping a cleaver to cut up the ego that will boil down into sweet ambrosia in a skull-cauldron. Skulls surrounding her terrify the uninitiated, but this is an image of transformation: The fire is the ultimate cleanser, the cooked nectar of self offered as “a practice of complete surrender to dharma.”

Oda describes herself as a tomboy and rebel from early on, and during her time at the Tokyo University of Fine Arts in the 1960s she was influenced by student uprisings against Japanese misogyny and an increasingly authoritarian culture. It was the time of the All Campus Joint Struggle Committee, an anti-government student resistance movement known as Zenkyoto, when “students, labor unions, writers, and artists united to demand equality, human rights, and the return of power to the people.” She also found personal freedom in a relationship with a brilliant American visiting teacher and graduate student, John Nathan (later a celebrated translator). Nathan held “the ticket for my liberation as a Japanese woman,” Oda writes, recalling a whirlwind romance, marriage, and university graduation that swept them into the artist community of 1960s New York City. By the 1970s, Oda was a mother of two boys and struggling to find her voice as an artist.

It is at this point in Oda’s narration that Sarasvati’s Gift reveals two photos for the first time in print: The first, a 1968 etching by Oda entitled Beauty Descending, is a full-frontal nude woman in full Neolithic fertility barely grazing lips with a disembodied being from the sky. Is this a whimsical homage to Michelangelo’s representation in the Sistine Chapel of the divine breath of life? Then on the opposite page Oda herself appears naked in the bath, joyfully bathing one son while pregnant with the other, resembling Beauty Descending, done two short years before. Oda was becoming that unique visionary who viewed her own female embodiment as the most powerful vehicle for personal transformation, both as an artist and as a disciplined Buddhist practitioner. This thinking was profoundly radical in both realms, dominated as they were by the artistic and spiritual concerns of the men who largely influenced them.

The second half of the book changes tone dramatically: Oda enters her fifth decade just as the US declares war in the Persian Gulf and Japan embraces nuclear energy. Her fear for the future of the planet propels her to merge the roles of artist and activist, as made evident by accounts of several public demonstrations where she used her thangkas to convey messages of purpose and drama.

It is here that one appreciates the design of the book: four chapters of life story separated by plates of the thangkas themselves. And it is through the short paragraphs Oda has written to describe her motivation and inspiration that we are able to see into the heart and mind of this remarkable woman. Much like Oda herself, the apparently separate parts of her life and work come together in Sarasvati’s Gift to create a refreshingly unique self-portrait.

♦