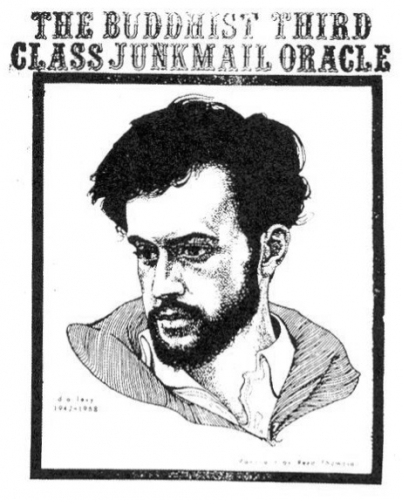

The Art and Poetry of d. a. levy

Edited with an Investigative Essay by Mike Golden

Seven Stories Press: New York, 1999

320 pp.; $21.95 (paper)

David Stanford

The Buddhist Third Class Junkmail Oracle: The Art and Poetry of d. a. levy is two books in one: the best of levy’s poetry and prose and editor Mike Golden’s ninety-page essay detailing levy’s story, an investigation that ponders this often-asked question: Did the intense, gifted 26-year-old, harassed for two years by police over “obscenity” issues, commit suicide, or was he assassinated? There are ample reasons for accepting the former theory, but there is enough strangeness in the saga of his persecution to understand why many who cared about levy have suspected the latter.

d. a. levy was a guiding light of Cleveland’s countercultural scene in the early and mid sixties. A prolific poet and publisher, he used a small hand press to churn out hundreds of chapbooks, pamphlets, magazines, and newspapers. In The Buddhist Third Class Junkmail Oracle and The Marrawhanna Quarterly, and under his various small press imprints, levy published many then-unknown writers, poets, and artists, including Charles Bukowski, R. Crumb, Tuli Kupferberg, and Ed Sanders. Many of his own longer poems reflect both his commitment to engaging life at street level and his wideranging interest in Eastern religious texts. In the introduction to one of the last editions of his ever-evolving long poem “The North American Book of the Dead,” he notes: “this poem is my hallucination, don’t get lost in it…it is not OH YEAH, it is not hip or cool. When i read the Tibetan Book of the Dead i was locked in a closet without a light, each page was a photograph in my pre-birth year book.”

Stories of the sixties usually focus on California and New York, but things got wild between the coasts, too. And especially in Cleveland, where cops and business leaders began to panic over the city’s local coffeehouse, the Well, which levy described as a magnet for bikers and poets and “spades.” In December 1966, levy, aggressively visible and prolific in print, was indicted by a grand jury for obscenity and busted. His case made levy a public figure as well as a local spokesman for the counterculture. He was arrested again in March 1967 for reading “obscene poetry” in public in the presence of minors, one of whom had been wired by the police. Jail cops, amused to hear levy was a Buddhist – and no doubt with the recent self-immolating anti-war protests by South Vietnamese monks in mind – suggested he pour gasoline on himself. Undeterred, levy decided to give Zen lectures in jail, and wrote the officers a note on toilet paper: “please don’t disrupt me with your questions if you see I am meditating.”

Eleven months after he was released from prison in 1968, levy was found dead in his apartment-killed by a .22 bullet, “opening his third eye,” as Golden puts it. According to many who knew him, levy’s spirit had been damaged by his prison ordeal. He had written often of death: “dont be afraid of death/they intend to murder you anyway.” One friend reported that levy always carried a lethal dose of seconal in his pocket. Although his death will most likely continue to be a mystery, what remains is a considerable body of material that is well worth exploring.

This rich anthology will find a home in several sections on the shelf: in “the Sixties,” in “Buddhism in America,” in “the zine revolution,” or in “poetry.” Countercultural enthusiasts will appreciate levy’s graphic art as well as his subversive writings. The book contains eleven covers of The Buddhist Third Class Junkmail Oracle, sixteen collages, ten “word images,” and the thirty-two collage-pages of “The Tibetan Stroboscope,” which levy describe as “an experiment in destructive writing.” Readers will appreciate the Buddhist moments in levy’s writing, like the poem “Tribute to Han Shan”; the Gary Snyder/Japhy Ryder reference in Cleveland Undercovers (though they never met, Snyder thought well of levy and referred to him in “Myths and Texts”); and his reference to Alice in Wonderland as “the western world’s greatest Zen text.” Following is an excerpt from levy’s look-back on his youth:

so at sixteen

still being a virgin forest

i decided

i must be a buddhist monk,

Then when people asked me

I TOLD THEM, I told them

“Not me, man, i don’t belong to No-thing”

According to poet Ed Sanders, levy “had the potential to be a great religious writer – a prophet.” In his twenty-six years he created a considerable body of writing and influenced many lives. It’s interesting to contemplate where his relentless energy would have taken him had he lived and remained rooted in Cleveland. Even thirty years after d.a. levy’s death, his work is by no means finished with this world.

David Stanford is a Californian-American who has worked eighteen years in the New York publishing industry. He is now an independent editor in Amenia, New York.

Image: Courtesy of Seven Stories Press.

The Red Thread

Buddhist Approaches to Sexuality

Bernard Faure

Princeton University Press: Princeton, 1998

352 pp.; $18.95 (paper)

The Red Thread of Passion

Spirituality and the Paradox of Sex

David Guy

Shambhala: Boston, 1999

288 pp., $23.95 (cloth)

Michael Sweet

Over the past decade or so, a number of scholarly and popular books and articles have been devoted to the connections between sexuality and religious experience. This has become a particularly fashionable subject for writers on Buddhism. However, such writers must face difficult contradiction these writers must face: How can the sex-positive ethics of the liberal and affluent developed world and the sex-negative ethics found in traditional Buddhist cultures be brought together? A prime example of this conflict is the ongoing controversy over what many regard as the Dalai Lama’s negative views on homosexuality. The great danger in writing on such topics is that we may read back into Buddhist texts our own desires and beliefs. At certain points, the authors of two new books on sex and spirituality have sometimes unwittingly succumbed to this tendency.

The Red Thread and The Red Thread of Passion have little in common other than a concern for the relationship between sexuality and religious/spiritual experience. The “red thread” in their similar titles is an allusion to the Japanese image of a thread of passion that runs through our lives. In The Red Thread, Bernard Faure has written what is essentially a study of sexuality in Japanese Buddhism from the medieval through the early modern era. Insofar as it sticks to this subject, the book has much to offer; Faure’s style is usually lively and fluent, and he brings together a large number of literary and historical sources, often with thought-provoking interpretations.

However, the first two chapters, which present a Buddhist “hermeneutics of desire” from a postmodern standpoint, are the least successful. Aside from the Foucauldian jargon, which will be off-putting to many readers, Faure often overgeneralizes. For example, he says that tantric Buddhism is “characterized by its extremism, its rejection of any morality, and its taste for despised aspects of social reality.” This is a vast oversimplification of a long and variegated tradition, and it ignores the many tantrikas who have maintained exemplary standards of morality. He also imagines that taking Bodhisattva vows abrogates the monastic precepts. Faure’s seemingly relative unfamiliarity with Indian Buddhism leads to his mistakenly conflating Hindu and Buddhist tantra. This section of the book also contains few sources or references, a serious deficiency in an academic work.

Once we get to Japan, Faure leads us on a well-documented tour of Japanese Buddhism, where wine-drinking, meat-eating, and heterosexual dalliance and concubinage were fairly common from an early period. For example, the eccentric fifteenth-century monk-poet Ikkyu Sojun consciously linked passion and sex with breaking through conventional concepts to enlightenment. He wrote poems about arhats in brothels, “sipping a beautiful woman’s sexual fluids,” masturbation, and comparing the scriptures to toilet paper.

Faure’s two chapters on same-sex relations in Japanese Buddhism are the best synthesis of this topic to date. Unique among Buddhist monastics, the Japanese not only covertly tolerated (male) same-sex sexuality, but openly celebrated it in collections of edifying tales about the love of monks for adolescent acolytes; this love is often tragic, but is portrayed as leading to spiritual growth. More disturbing is a ritual that Faure describes, a homosexual variation of heterosexual tantra, in which an acolyte was first annointed as a deity, and then “forced” or raped by the head priest; this clearly seems to constitute sexual abuse.These latter chapters render this book quite useful to those with an interest in sexuality and religion in Japan.

David Guy’s The Red Thread of Passion is much more accessible to the nonspecialist reader. His writing springs from his personal concerns with sexuality and spirituality, and he has no academic pretensions. Besides tracing his own journey from a compulsive genital sexuality to a more relaxed, whole-body eroticism, Guy provides a series of vivid portraits of people who in their lives and writings have advocated sexuality/sensuality as a means to transcendence.

The two chapters most directly pertaining to Buddhism are those about Walt Whitman and Alan Watts. Guy presents Whitman, the great American poet of male love, as a kind of solitary Buddha who achieved a satori-like state through a spontaneous nature-mysticism. There is no doubt about Whitman’s greatness as a poet and prophet: he has a compassionate and noble view of all living and nonliving things. Yet his thought did not spring out of a vacuum, as the reader of this book might be led to believe. His pantheism was profoundly influenced by the Transcendentalist thought of Emerson and Thoreau, whose works he revered. Although it was Emerson himself, as Guy notes, who first gave Whitman the appellation of “American Buddha,” the Transcendentalists’ knowledge of Buddhism, compared to their understanding of Hinduism, was sketchy at best. Whitman’s work is permeated with tenderness and the desire to touch the young men in whose beauty he found a reflection of the divine; the poems are moving and delightful, but a far cry from normative Buddhist ideals of detachment. With the strain of mystical eroticism in his poetry, Whitman might be more accurately compared to an American Rumi or Mirabai.

Watts was a seminal figure in the emergence of Buddhism in midcentury; he never claimed to be a scholar, but his original writings had a deep impact on American Buddhism. In retreat from a very unhappy and rigidly controlled childhood (leavened by his mother’s affection and love for Asian art), Watts embraced sexual freedom in the name of Zen, and practiced this in his personal life. Guy chronicles Watts’s success as a writer and public figure – as well as his sometimes messy private affairs – to his sad premature death from the effects of alcoholism. Besides Whitman and Watts, Guy discusses D. H. Lawrence, the late pornographer and sexual theorist Marco Vassi, and contemporary masseurs, sex workers and porn actors, sympathetically depicting their varied sexual practices and theories about sexual energies, healing, and spirituality. While it lacks detailed historical context or critical analysis, The Red Thread of Passion is an entertaining introduction to some striking personalities and perennially intriguing issues.

Both these books, despite their vast differences in style and subject, stress the role of sexual transgression in spiritual life. The peril here is falling into the extreme of seeing the eccentric as normative. Faure explains his own emphasis by citing the much greater ease of locating transgressions in the texts. This seems disingenuous, however, as there are numerous written records of “normal” behavior, including the well-known Chinese collection The Lives of the Eminent Monks, which is full of tales of strictly celibate monks. In the end, it may be simply that for most of us, wild and crazy people are much more enjoyable to read about than blamelessly holy ones. As work continues on sexuality and spiritual practice, perhaps the dialectical process will result in a middle way, in which the celibate and the profligate, the vanilla and the kinky, will all take their rightful place.

Michael Sweet is a psychotherapist, teacher, and writer living in Madison, Wisconsin. He has published articles and book chapters on Buddhism, the history of sexuality, and mental health, and is currently collaborating on a translation and study of two Tibetan mental training texts.

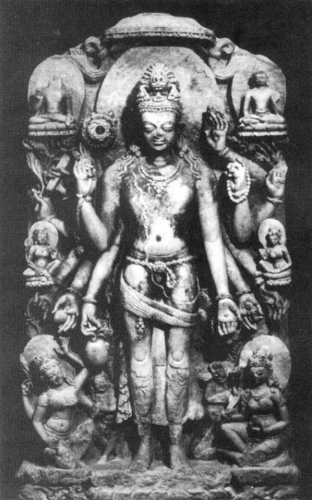

Image: Siva and Parvati. Photo © Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Circling the Sacred Mountain

A Spiritual Adventure through the Himalayas

Robert Thurman and Tad Wise

Bantam: New York, 1999

356 pp.; $25.95 (cloth)

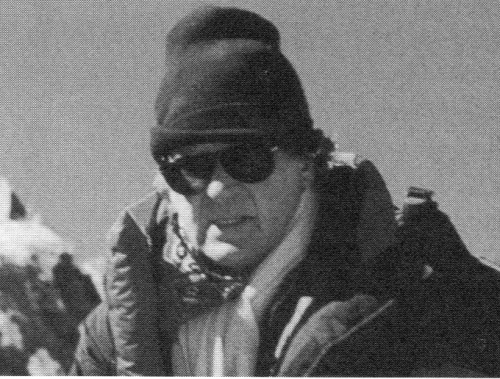

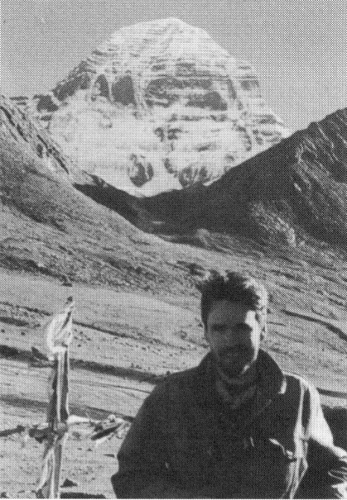

Tales of high adventure are all the rage. Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air and Sebastian Junger’s The Perfect Storm have topped bestseller lists recently, and stories of sea-soaked, sand-swept, and ice-bound escapades crowd bookstore shelves. It’s not just armchair daredevils who benefit from this trend. La-Z-Boy spiritual seekers profit as well, for the very best adventure tales – Ernest Shackleton’s South, for instance, about his legendary Antarctic voyage, or T. E. Lawrence (of Arabia)’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom – invariably detail extraordinary journeys inward as well as outward. So, too, does Circling the Sacred Mountain, the worthy latest book from the indefatigable pen of renowned Buddhist scholar Robert Thurman (Inner Revolution), who here mixes ink with a family friend, Tad Wise, a stonemason and novelist (Tesla).

The “sacred mountain” of the book’s title is Mount Kailash, a diamond-shaped peak located in the Himalayas of western Tibet that, as Thurman puts it, “is the axis mundi, the cosmic pillar that upholds the vault of heaven,” the place where the Buddha “is said to have manifested himself . . . as the Superbliss-Machine Buddha.” Since 1971, Thurman had dreamed of visiting Mt. Kailash and of planting on its face his “deepest wish for the universe” and possibly changing the world by doing so. By May 1995, this professor of Religion at Columbia University had put his dream into action, organizing an expedition of eight “pilgrims all at different points in the Buddhist path.” That month, a ninth pilgrim appeared in the person of Wise, an erstwhile student of Thurman’s and of the dharma who, as if hearing a call, impulsively signed on to the expedition after running into Thurman in a coffee shop and listening to him rhapsodize about the mountain and its powers.

In Circling the Sacred Mountain, Thurman and Wise take turns recounting their trip to Mt. Kailash. Thurman’s passages focus on the inner aspects of the voyage, while Wise’s concentrate on the outer, though neither exclusively so. Wise’s contributions ground the book as travelogue. Through his words, readers experience the tricky border-crossing into Tibet: Will Thurman, a longtime friend of the Dalai Lama, be turned back by Chinese guards? Wise carves prose that’s generally clean-hewn but occasionally overworked (often “stunned” by events, he finds himself, upon carrying a heavy stone, “in silent agony, lungs bursting, black splotches blooming before my eyes, transformed into an old man from commedia del’arte, stooped, broken, choking, ready to die” – that, is, pooped). He sculpts a memorable word-frieze of the peoples and landscapes of Tibet and of his journey through them, of hazardous drives and climbs, of a visit to Milarepa’s cave, campfire chats, bouts of altitude sickness, concerns over making sense of his pilgrimage and of his complicated relationship with Thurman. It’s an honest, observant, self-deprecating account of one man’s journey into the unknown. Eight pages of color photographs illustrate the text but present pictures no more vivid than Wise’s words.

Thurman’s contributions are something else entirely, and marvelous. They are, for the most part, dharma talks, presumably modified transcriptions of the regular lectures that he gave during the journey and that Wise tape-recorded. The early talks, presented as the pilgrims travel toward Mt. Kailish, concern meditation themes from the Tibetan Lamrim tradition, the Systematic Path of Enlightenment: on the infinite consequentiality of one’s actions, for instance, or on techniques for the attainment of compassion. When the band of nine reaches the mountain, Thurman turns to lectures based on the ancient, esoteric tantric teaching known as The Blade Wheel of Mind Reform, which, he explains, “is designed to kill the ego to save our lives.”

Those who have heard Thurman talk know that he is a Paganini of dharma-patter. His verbal virtuosity shines on these pages, as does his immense talent as a teacher, his ability to relate Buddhist ideas to everyday life (on life as suffering: “Look at people who have the things you think you want. Look at the president of the United States. You begin to realize the guy has got a permanent headache”) and to inspire students to go further, much further (“Your mentor or mentors, he or she or they, are delighted that you’re reflecting on these deep themes. Their pleasure at your understanding flows toward you as a cascade of nectar”).

At times Thurman seems to grow giddy with delight at the teachings (“Nirvana is bliss-void-indivisible, it is permanent orgasm”) but, carried irresistibly along by his good vibes, dharma adventurers will come to share his joy. Leaping from their La-Z-Boys, they will conclude their reading of this book as Thurman concludes his writing of it, with the hearty affirmation that “All is well!”

Jeff Zaleski, a contributing editor to Tricycle, is an editor at large at Publishers Weekly.

Photos courtesy of Bantam Books.

Image 1: Robert Thurman near the top of Drolma La (Tara Pass) at 18,500 feet.

Image 2: Tad Wise in front of the western face of Mt. Kailash.

Zen and the Writing Life

Peter Matthiessen

Audio Wisdom

Running time: 2 hours

$18.95

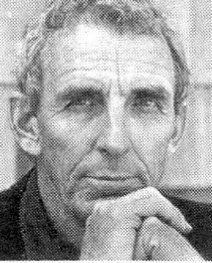

Jacqueline Jens

Zen and the Writing Life, a tape featuring Peter Mathiessen, was recorded live by Audio Wisdom at the San Francisco Zen Center as part of their series of talks on Buddhism at Millennium’s Edge. The tape presents a writer at once familiar and abundantly multidimensional. This medium lends itself well to Matthiessen’s spoken narrative of his life as a writer, told in the great storytelling style of his many works for which he is best known – The Snow Leopard, Far Tortuga, At Play in the Fields of the Lord, In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, and the Watson trilogy, to name just a few.

To actually hear the voice of Peter Matthiessen offers an immediate entree into the magic of his word mastery. From beginning to end, these tapes reveal his economy of spoken language. His consonants are crisp while his talk seamlessly weaves an engaging nonlinear pattern of anecdotes about his writing; how-to advice for writers on structure, plot and organization; stories of his Buddhist teachers; and humorous asides on the trials and tribulations of sitting practice.

The tape also cover much background about some his best known works as an environmental and human rights activist. Hearing him speak of Caesar Chavez and Leonard Peltier, the listener understands that the primary function of the writer, according to Matthiessen, is to speak for those who cannot speak for themselves, to help them care for one another – for the purpose of life is to be merciful. The extent to which he has done so on behalf of sentient planetary life through his intrepid journeys across every continent remains the central, most telling theme of his writing.

It is in attention to detail that the practice of Zen and that of writing meet on common ground. In relating Basho’s oft quoted haiku, “The old pond/ frog jumps in/ phish,” Matthiessen’s “phish” sounds sharply with the heightened wake-up quality of transmission. For a practitioner, paying attention to the moment results in a “refreshing of mind,” while the writer’s attention to the moment helps him to express his thoughts in a new way. On several occasions, Matthiessen asserts that to meditate, you pay attention to the moment, and a widening of your vision, an opening out toward phenomena, naturally occurs. It is this open mind that is the writer’s mind, where, he says, “You don’t miss anything.” Matthiessen maintains that the challenge of the writer is to find the detail that represents the whole, to describe the vivid split second that pierces to the heart of everything. This is the ‘ordinary mind’ of direct perception, familiar to practitioners and writers alike.

Much of Matthiessen’s discussion about writing focuses on the principal Buddhist tenet of language: It is, at best, the proverbial finger pointing to the moon, what the early Buddhist elders designated as prajnapti. Fortunately for us, Matthiessen has not kept silent, but instead made language the vehicle of his inspiration.

For writers, Matthiessen’s craft treatment of language will convey many useful pointers. He is a great keeper of dog-eared spiral notebooks which fit into his big shirt pocket. Keep the left page blank, he tells us, in case you want to add something later such as related notations or references. He is a maker of charts for structure and, in research, a thorough scientist. In speaking of image, his advice is priceless: Don’t clump all your good images onto one page like a bunch of dinosaurs clashing, but set them jewel-like in the midst of clear prose to highlight them. For practitioners, his advice is applicable to most any spiritual discipline. To the casual listener – the one who is neither writer nor practitioner – Zen and the Writing Life will offer an excellent introduction to the merits of being present to the moment. In that, Audio Wisdom lives up to its name.

Jacqueline Jens worked for many years at the Naropa Institute and for the late poet Allen Ginsberg. She currently lives in New England where she is an administrator for Namkhai Norbu Rinpoche’s Dzogchen Community of America as well as program director for the Great River Arts Institute.

Selected Non-Fictions

Luis Jorge Borges

Viking: New York, 1999

550 pp.; $40 (cloth)

Donald S. Lopez

In celebration of the centenary of the birth of the great Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), Viking is publishing three volumes of his works: Collected Fictions, Selected Poems, and Selected Non-Fictions. Borges is an author beloved by scholars because of his bibliophilia, particularly remarkable in a man who lost his sight in midlife (1955). His works are filled with references to the most obscure tomes of scholarship, made all the more intriguing because the reader is often left to wonder whether their titles are products of Borges’ imagination. In famous works like “The Library of Babel” and “Pierre Menard: Author of the Quijote,” Borges both evokes and parodies the obsessions of the life of the mind.

It is clear from one collection of lectures, entitled “Seven Nights” (1980), that Borges had a deep appreciation for Buddhism. That appreciation is also evident in two short essays in Selected Non-Fictions, both written in the years before his blindness. In the first, “Personality and the Buddha,” written in 1950, Borges raises the well-worn question of whether it is doctrinally accurate to speak of the Buddha as having a distinctive personality. This question no longer holds much interest for scholars of Buddhism. Nonetheless, Borges’ essay is delightful for his retelling of the life of the Buddha and for his predictably unexpected references to Chaucer, Proust, and Peer Gynt. One sees here, as elsewhere, that Borges was well versed in the European scholarship on Buddhism; he makes references, for example, to such largely forgotten fathers of the field as Hardy, Beckh, and Kern.

In the second essay, “Forms of a Legend,” written in 1952, he again considers the story of Prince Siddhartha. Pondering the baroque version that appears in the Lalitavistara (where “the history of the Redeemer is inflated to the point of oppression and vertigo”), Borges asks what it could possibly mean for an already enlightened Buddha (for in the Mahayana, the Buddha was enlightened long before his birth as the prince) to cause the gods to create the four sights – the old man, the sick man, the corpse, and the mendicant – in order that the prince may pretend to be repelled by the first three and inspired by the fourth. Borges argues that it is a dream dreamt by Siddhartha or, more accurately, a dream that no one dreams. But Borges, as always, is ready to defer to the opinion of others. Here he notes Oscar Wilde’s variation on the story of Siddhartha, in which the prince happily lives out his days without ever leaving the pleasures of the palace. Upon his death, his statue is placed high on a pedestal, a statue that can be seen, and thus see, beyond the palace walls. It is only then that the prince discovers sorrow. Always ready to question his own authority, to move the perspective of the apparently mythical past to the apparently real present, Borges concludes, “it would not surprise me if my history of the legend was itself legendary, formed of substantial truth and accidental errors.”

These lectures comprise only eight pages of a 550-page book filled with essays on authors famous and forgotten, with film reviews, book reviews, prologues, and learned discourses on all manner of arcane matters. Included here is the author’s famous essay on Kafka, where he made the statement, oft-quoted by scholars of literature, that “each writer creates his precursors.” This is an insight worthy of reflection in Buddhism, a tradition concerned in so many ways with authority and lineage.

Donald S. Lopez is Professor of Buddhist and Tibetan Studies at the University if Michigan. His most recent book is Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West (University of Chicago Press).Tibet, Tibet

Tibet, Tibet

$15.97

Coming Home

Yungchen Lhamo

Real World Records Ltd.

Dimitri Ehrlich

Yungchen Lhamo is a Tibetan-born singer who fled to Australia where she developed considerable standing as a movie actress before embarking on a career as a recording artist. Peter Gabriel’s RealWorld label has released two albums by Lhamo, which have garnered critical acclaim but have yet to earn her the widespread audience her exquisite talents deserve. The first, Tibet, Tibet, came out in 1996 and is comprised mainly of Lhamo singing arrestingly sonorous a capella renditions of Tibetan Buddhist mantras. Lhamo’s voice has a naked, unadorned splendor, and in this era of high-tech musical production, it’s refreshing to hear an album so underproduced.

Tibet, Tibet begins with “Om Mani Padme Hum,” a mantra so ubiquitous among Tibetans that it has been called the Tibetan national prayer. Lhamo breathes a sensuality into the prayer that may unnerve traditionalists who are uncomfortable with the marketing of mantras as entertainment. But for those who approach this album without any prior knowledge of Tibetan Buddhism, or judge it from a purely musical point of view, Tibet, Tibet is a listening experience of stark beauty. It’s the kind of music that demands one’s full attention; try putting it on in the background, and soon you will have stopped whatever you were doing. With precise, understated power, Lhamo’s singing has a regal quality that takes you by the shoulders, looks you in the eyes, and slowly hypnotizes you. Although there are a few ritual Tibetan drums and bells, most of Tibet, Tibet features Lhamo’s lone voice, offering the refuge prayer and other essential Tibetan Buddhist mantras, in stately, mesmerizing tones.

Lhamo’s second album, Coming Home, is a departure, with more complex musical productions. Some songs, such as the title track, feature spare, elegant arrangements of violin and acoustic guitar that perfectly frame the sadness in Lhamo’s voice. For example, the album begins with the ironically titled “Happiness, Is . . .”, an almost unbearably tender melody that suggests the tranquility of hopelessness.

But while Coming Home is more richly textured than Tibet, Tibet, by attempting to update Lhamo’s sound and infuse her music with more contemporary musical elements, her producer, Hector Zazou, has inevitably made a few missteps. To begin with, it’s extremely difficult to take a voice as pure as Lhamo’s and place it in a hip musical soundscape. In musical terms, there is always a razor’s edge between sweet and saccharine. On dreamy, pulsating ambient tracks like “Sky,” Zazou achieves a richness that’s not cloying. But at other times, he falls into the murky waters of New Age pabulum, which distracts from the dignity of Lhamo’s nuanced singing.

Although Coming Home is a fine album with many tastefully arranged tracks to recommend it, if you’re just discovering Lhamo, Tibet, Tibet offers a more straightforward introduction to the glacial beauty of her voice. Both albums, however, feature some of the finest musical moments by any singer – in any genre – in recent years.

Dimitri Ehrlich is a songwriter whose most recent album, As Nervous as You (Tainted Records), explores Buddhist themes. He is also the author of Inside the Music: Conversations with Musicians about Spirituality, Creativity, and Consciousness (Shambhala).

Image: Yungchen Lhamo from the Tibet, Tibet CD booklet.

Books in Brief

An annotated selection of new noteworthy guidebooks, teachings, and scholarly texts

Calm Abiding and Special Insight

Achieving Spiritual Transformation Through Meditation

Geshe Gedun Lodro

Translated by Jeffrey Hopkins

Snow Lion Publications, $19.95

This book treats the subjects of shamatha and vipassana in a detailed and systematic way, providing an exhaustively intricate guide to the Tibetan methods of developing calm abiding and special insight. Shamatha-vipassana is often considered a practice for beginners, but this book is for advanced practitioners—newcomers are likely to be confused by issues such as, Would that teacher necessaerily be in the Desire Realm or might she or he be invisible? However, for Tibetan practitioners with specific questions about how shamatha-vipassana relates to the Bodhisattva path, tantra, or enlightenment, this book will prove valuable.

The Practice of Vajrakilaya

Khenpo Namdrol

Snow Lion Publications, $12.95

The visualization and mantra practices specific to Vajrakilaya, a Tibetan wrathful deity, are considered to be a powerful method for removing obstacles to wisdom and compassion and for purifying spiritual pollution. In a short but detailed collection of teachings delivered orally in Maryland in 1995, Khenpo Namdrol, abbot of the largest Nyingma study college outside of Tibet, leads the reader through the stages of visualization and purification.

Boundless Heart

The Cultivation of the Four Immeasurables

B. Alan Wallace

Edited by Zara Houshmand

Snow Lion Publications, $14.95

B. Alan Wallace brings a Tibetan Buddhist perspective to this volume on the Theravadin teachings designed to cultivate lovingkindness, compassion, equanimity, and empathetic joy. The teachings are drawn from the Visuddhimagga, the primary text of the great fifth-century scholar Buddhaghosa. Wallace also discusses the practice of shamatha meditation.

Foundations of Tibetan Buddhism

Kalu Rinpoche

Snow Lion Publications, $16.95

The meditation master Kalu Rinpoche is a figure beloved by many in the West, where he repeatedly gave teachings beginning in 1971. This book gives a full discussion of the path of the Kagyupa school, including taking refuge, prostrations, purification, guru yoga, mandala practice, and Mahamudra. His instructions will prove very clear and useful to students of that path.

Image: Courtesy of Snow Lion Publications.

Tranforming the Heart

The Buddhist Way to Joy and Courage

Geshe Jampa Tegchoh

Edited by Thubten Chodron

Snow Lion Publications, $14.95

If you don’t examine your own errors,

You may look like a practitioner

but not act like one.

Therefore, always examining your own errors,

Rid yourself of them—

This is the practice of Bodhisattvas.

Geshe Jampa Tegchok uses The Thirty- seven Practices of Bodhisattvas, a text revered by all the Tibetan schools of Buddhism, as the basis for this insightful commentary on the path to enlightenment. Exchanging self for other, the importance of having good friends, and the liberating nature of emptiness are all discussed.

Image: Courtesy of Snow Lion Publications.

Realizing Emptiness

Madhyamaka Insight Meditation

Gen Lamrimpa

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

Snow Lion Publications, $14.95

Gen Lamrimpa spent twenty years in solitary retreat before he was requested by the Dalai Lama to teach in a more active manner. In Realizing Emptiness: Madhyamana Insight Meditation, he draws on the Madhyamaka method of analysis to point the way to realization of ultimate emptiness. He also discusses the relationship between Dzogchen and Madhyamaka.

Transcending Time

An Explanation of the Kalachakra

Six-Session Guru Yoga

Gen Lamrimpa

Translated by B. Alan Wallace

Wisdom Publications, $21.95

In Transcending Time, Gen Lamrimpa tackles the Kalachakra Tantra, one of the highest yoga tantras, which deals with the legend of a future Buddhist paradise. He gives an overview of all stages of each phase of the tantra that should prove accessible and enlightening to all interested practitioners.

Asian Religions in Practice

Edited by Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

Princeton University Press, $15.95

This book collects and reprints the introductions to the first five volumes in the Princeton Readings in Religions series, volumes covering India, China, Tibet, Japan, and Buddhism. The series has presented a massive amount of material to readers and has worked to break down old stereotypes by focusing on the rich diversity of practices in each tradition.

Emptiness in the Mind—Only School of Buddhism

Dynamic Responses to Dzong-ka-ba’s The Essence of Eloquence: Vol. I

Jeffrey Hopkins

University of California Press, $45

Emptiness is the most crucial, and most elusive, concept in Buddhism. Hopkins uses the writings of the fourteenth-century Tibetan philosopher Dzong- ka-ba (Tsongkhapa), founder of the Gelugpa school, and the commentaries of his critics to weave a complex picture of competing and intersecting views of emptiness. If the 458 pages of text, 774 footnotes, and 27 pages of bibliography don’t satisfy your interest in the subject, don’t worry—this is only the first volume in a three-part series.

Buddhism and Politics in Twentieth-Century Asia

Edited by Ian Harris

Pinter, $75

Drawing on events and social movements throughout Buddhist Asia, this volume systematically demolishes the a antiquated view that there’s no connecition between Buddhism and politics. The complex relationships between Buddhism and the military, government, and social order in ten different countries are explored, offering a window on the ways in which Asian Buddhists draw on their religious heritage to inform their political actions.

The Psycho-Ethical Aspects of Abhidhamma

Rina Sircar

University Press of America, $28.50

Abhidhamrna, the philosophical writings of the ancient Theravadin teachers, has a reputation for being stuffy and impenetrable. The fearsome title of The Psycho-Ethical Aspects of Abhidhamma isn’t likely to dilute that impression, but this book is a good volume for Westerners interested in learning more about this part of the Buddhist canon. Rina Sircar is a Burmese-born teacher and scholar in the Theravadin tradition who has been teaching in the West for twenty-five years (currently at the California Institute for Integral Studies). She uses the experience gained through contact with Westerners to relate the Abhidhamma teachings on the nature of the self in an understandable and educational way.

Questions From the City, Answers From the Forest

Simple Lessons You Can Use from a Western Buddhist Monk

Ajahn Sumano Bhikkhu

Quest Books, $16

In a straightforward and accessible question-and-answer style, Ajahn Sumano Bhikkhu deftly responds to the concerns of inquisitive laypeople. Ajahn Sumano, a Chicago-born monk ordained in the Theravadin tradition, wrote this book in forty- minute chunks on an old battery-powered laptop in his jungle cave in Thailand. The peculiar circumstances of the book lend its advice a clear and succinct quality, whether the topic is getting “unstuck” from modern society or dealing with annoying mosquitoes.

Subtle Wisdom

An Introduction to Ch’an Buddhism

Master Sheng-yen

Doubleday, $9.95

Ch’an is the great Chinese school of meditative Zen Buddhism. In Subtle Wisdom Master Sheng-yen, a lineage holder in both of the two major surviving schools of Ch’an, offers a refreshing Chinese perspective on concepts discussed by Zen practitioners, such as sitting practice, suffering, compassion, and enlightenment.

The Zen Works of Stonehouse

Poems and Talks of a Fourteenth-Century Chinese Hermit

Translated by Red Pine

Mercury House, $14.95

“You rush around waving scissors and tape busy all day with needle and thread when you’re done measuring others do you ever measure yourself?”

Red Pine’s excellent translation of the poetry and dharma talks of the Chinese Ch’an master Stonehouse will excite scholars, poets, and practitioners alike.

Twelve-armed Avalokitesvara from Rob Linrothe’s Ruthless Compassion: Wrathful Deities in Early Indo-Tibetan Esoteric Buddhist Art (Shambhala Publications, $55). Artwork from the sixth through thirteenth centuries is used to trace the evolution if the wrathful diety motif in tantric Buddhist representation and practice (left). Photo courtesy of Shambhala Publications.

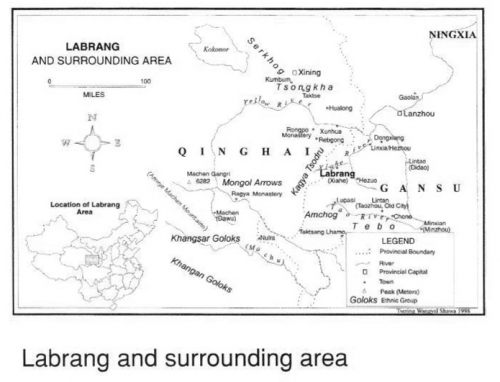

Labrang

A Tibetan Buddhist Monastery at the Crossroads of Four Civilizations

Paul Kocot Nietupski

Snow Lion Publications, $24.95

Between 1922 and the Communist invasion in 1949, Marion Griebenow and his family spread the message of Christianity in the eastern Amdo region of Tibet.Labrang is based on the thousands of photographs and extensive notes they took while performing medical services, preaching the Christian gospel, and learning from and about their neighbors in this ethnically diverse area. The book contains much information about eastern Tibet in the years before the Communist takeover, especially focusing on an important Gelugpa monastery in the area. The thoughts and insights of the Griebenows, both as collectors of cultural data and as Western missionaries thrown into an Asian Wild West, prove quite interesting and illuminating.

Image: Courtesy of Snow Lion Publications.

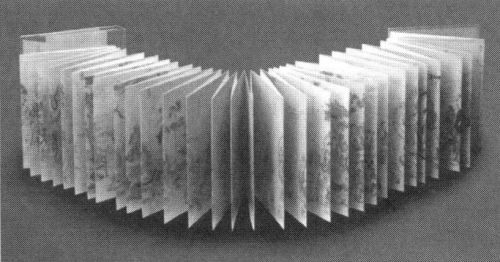

The Buddha Scroll

Ding Guanpeng

Introduced by Thomas Cleary

Shambhala Publications, $25

A true treasure to study and cherish, The Buddha Scroll is a reproduction of an eighteenth-century Chinese Buddhist scroll, itself a reproduction of an original scroll created in the twelfth-century. Thomas Cleary provides an introduction and a key to the 36-foot-long accordion-folded scroll, describing the myriad Buddhas, bod- hisattvas, deities, monks, and other luminaries depicted in the painting. The scroll is a fascinating and inspiring glimpse of the extravagant world of ancient Chinese Buddhism.