Walter Evans-Wentz didn’t speak Tibetan and he never translated anything, but he was known as an eminent translator of important Tibetan texts, especially a 1927 edition of The Tibetan Book of the Dead, which was for many Westerners the first book on Tibetan Buddhism that they took seriously. “He didn’t claim to be a translator in his books,” says Roger Corless, Professor of Religion at Duke University, “but he didn’t mind leaving the impression that he was.”

Like many figures who played important roles in bringing Buddhism to the West, Evans-Wentz didn’t call himself a Buddhist, and he seems to have stumbled almost accidentally upon the texts he eventually published. With his naive sincerity, flowery rhetoric, lofty vision, and messianic tone, he might be taken today for a proto-New Age crank.

Nonetheless, he became a highly respected scholar. He even projected a vaguely British affect in his writings, signing his books “W Y Evans-Wentz, M.A., D.Litt; D.Sc. Jesus College, Oxford.” But Evans-Wentz spent comparatively little time at Oxford and actually grew up before the turn of the century in Trenton, New Jersey.

The man who would later praise the hermit ideal was a dreamy, lonely youth who liked to spend his afternoons lazing beside the Delaware River, sometimes without his clothes. On one of those afternoons he had an “ecstatic-like vision,” and remained “haunted” by the conviction that “this [was] not the first time that I [had] possessed a human body,” but now “there came flashing into my mind with such authority that l never thought of doubting it, a mind-picture of things past and to come…. I knew from that night my life was to be that of a world pilgrim, wandering from country to country, over seas, across continents and mountains, through deserts to the end of the earth, seeking, seeking for I knew not what.”

Evans-Wentz did become a pilgrim, wandering through Egypt, India, Sikkim, China, and Japan. He was particularly mobile between the two world wars, when he worked on The Tibetan Book of the Dead.

Throughout his life, he kept diaries and he made extensive notes for an autobiography that served as a source for Ken Winkler’s brief 1982 biography, Pilgrim of the Clear Light. He also made substantial reference to himself in his books, especially in the long introductions in which he supplied background material. But there remains something essentially mysterious about the man. He wore his spiritual heart on his sleeve, but other parts he kept concealed.

Evans-Wentz had two brothers and two sisters, but was a solitary child. His father was of German descent, a businessman who had a problem with alcohol. His Irish mother may have inspired his early scholarly interests (his first book, written at Oxford, was called The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries).

Walter was raised a Baptist, but as he grew older the family began to embrace the ideas of spiritualists and freethinkers. He had a particular interest in the occult and was much taken with the work of Madame Blavatsky, founder of the Theosophical Society. It was because Blavatsky claimed to have been inspired by lamas in Tibet that he first became interested in that remote Himalayan culture. Indeed, much of his work comes into focus in light of his interest in the Theosophists. He shared their visionary, exalted tone (“Over the bosom of the Earth-Mother, in pulsating vibrations, radiant and energizing, flows the perennial Stream of Life,” he wrote in one introduction). He saw truth in all religions but held a lifelong grudge against Christianity, which he regarded as small-minded and petty. Reincarnation is the single thread that runs through all his work: insisting that Gnostic Christians had believed in rebirth, he could not understand why the mainstream faith had abandoned this doctrine.

Evans-Wentz had a fickle relationship to capitalism. The idea of an ascetic life attracted him, especially after he had visited the East, and he disliked any show of wealth or bourgeois comfort. But he followed his father into the real estate business and was remarkably successful, making substantial sums in “quick sales, mortgages, and land transfers.” He would continue to deal in real estate all his life, and apparently funded himself with the profits.

He didn’t get around to formal education until his mid-twenties. He had followed his father to San Diego, partly because he was interested in Loma Land, the American headquarters of the Theosophical Society, and he enrolled at Stanford University at the age of twenty-four as a “special entrant.” By the time he applied to Jesus College at Oxford in 1907, at the age of twenty-nine, he had earned both bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Stanford. At Oxford he pursued his interest in “fairy faith,” traveling through Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Cornwall, Brittany, and the Isle of Man, collecting stories about pixies, fairies, and goblins.

By 1916, Evans-Wentz had a monthly income of $1,600 from his investments, a princely sum in those days. He visited two poets in Ireland, George William Russell and William Butler Yeats, both of whom had an interest in his work and in Theosophy; then he began his wider travels, heading first for Egypt, where he remained for 29 months. Roger Corless speculates that it was Evans-Wentz’s probable knowledge of E. Wallace Budge’s translation of The Egyptian Book of the Dead that left us with the inaccurate title The Tibetan Book of the Dead. (A more literal translation would be The Book of Liberation by Hearing in the Intermediate States.)

From Egypt he moved on to Ceylon and then to India, where he mingled with the prominent Theosophist community there. Until then, he had taken an occultist’s interest in varieties of faith, not a practitioner’s. But now he was in the land that had inspired Madame Blavatsky, and he began to wander in the foothills of the Himalayas, encountering the spiritual teachers about whom he would write in his books.

In Darjeeling, Evans-Wentz met the headmaster of a boys’ school in Gangtok, Sikkim, named DawaSamdup. Dawa-Samdup had acted as an interpreter to the British government in Sikkim and was working on a Tibetan-English dictionary. But apparently he wasn’t much of a headmaster. He was “cursed by the demon drink,” according to the Winkler biography, and would wander away from the school for days at a time, neglecting his students while he “contemplated on metaphysical planes.”

But Dawa-Samdup was devoted to his work as a translator. During his travels, Evans-Wentz had bought various sacred manuscripts; Kazi Dawa-Samdup possessed others. The two men would get together in the early mornings to pore over these texts, with Kazi Dawa-Samdup doing the actual translating and Evans-Wentz acting as his “living dictionary.” According to Rick Fields in How the Swans

Came to the Lake, Evans-Wentz was “unable to refrain completely from seeing Tibetan Buddhism through the lens of the comparative religion and folklore in which he had trained at Oxford,” and “his version contained certain inaccuracies: the diction, for example, with all its ‘ye’s’ and ‘thou’s,’ suffered from biblical rhetoric, and Evans-Wentz had failed to adequately distinguish between Hindu and Buddhist terminology.”

Yet Fields also acknowledges the vast influence this text had in introducing Tibetan Buddhism to the West. Three years before its publication, scholar J. B. Pratt had said that Tibetan Buddhism was “so mixed with non-Buddhist elements that I hesitate to call it Buddhism at all.” But Evans-Wentz saw Tibetan Buddhism not as a corrupted but as a more elaborate and advanced form of Buddhism; not “in disagreement with canonical, or exoteric, Buddhism, but related to it as higher mathematics is to lower mathematics, or as the apex of the pyramid of the whole of Buddhism.” Fields calls this insight EvansWentz’s greatest achievement.

In 1922, just three years after the two men had begun to collaborate, Kazi Dawa-Samdup died. Evans-Wentz had become more serious about spiritual practice during this period, living in a grass shack and struggling, he later wrote, to “gain some actual insight into the actual practice of yoga.” He considered himself Kazi Dawa-Samdup’s disciple, though there is no evidence that the Tibetan saw himself as the guru. Evans-Wentz loved practicing in rural India and considered it a sacred space, a concept he continued to develop through the years. “All holy places,” he wrote in The Theosophical Forum in 1942, “in varying degrees have been made holy by that same occult power of mind to enhance the psychic character of the atom of matter; they are the ripened fruit of spirituality, the proof of thought’s all-conquering and alltransforming supremacy.”

The period between Kazi DawaSamdup’s death and the outbreak of World War II was one of almost frantic activity for Evans-Wentz. He traveled among the three places that had meant the most to him: India, England, and California. And he continued to work as a “compiler and editor” of the texts his teacher had translated, following The Book of the Dead with Tibet’s Great Yogi Milarepa in 1928. The earlier book had set out what Evans-Wentz called “the art of knowing how to die”; the latter he described as setting out “the art of mastering life.”

He followed Milarepa in 1935 with what he regarded as the third book of a trilogy, Tibetan Yoga and Secret Doctrine, convinced that “it is only when the West understands the East and the East the West that a culture worthy of the name of civilization will be evolved.” His work by that time had taken on a decidedly anti-Western tone. He believed not just in the texts he had discovered, but in the way of life he had found.

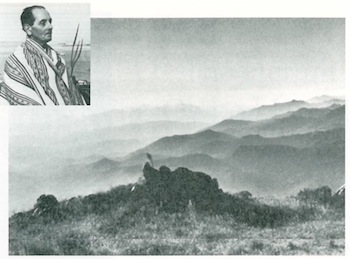

And then Evans-Wentz’s life took a turn that seems both utterly bizarre and entirely characteristic: At the outbreak of World War II, the world traveler and renowned scholar fled to a small room in the Keystone Hotel in San Diego, where he lived out the last twenty-three years of his life. He chose the Keystone because it was near the city’s only vegetarian restaurant—the House of Nutrition—and near the public library, where he sometimes checked out his own books because he had given all of his copies away. He also had discovered his own sacred space, Mount Cuchama, a few miles away near the Mexican border. Like the real estate speculator he had been all his life, he bought up as much of it as he could. He owned a small house on his land, and went there sometimes to practice “the Dharma, the Buddhist ‘way of truth.'”

In one of his book introductions, he praised what he called the “hermit ideal,” men who lived the “rigors of the snowy Himalayas, clad only in a thin cotton garment, subsisting on a daily handful of parched barley.” Evans-Wentz had really been a hermit all his life, and with his threadbare clothing and spartan diet, he continued to live that way in San Diego.

“I am haunted by a realization of the illusion of all human endeavors,” he wrote in a late diary. “As Milarepa taught: buildings end in ruin, meetings in separation, accumulation in dispersion and life in death. Whether it is better to go on here in California where I am lost in the midst of the busy multitude or return to the Himalayas is now a question difficult to answer correctly” But Evans-Wentz did finally answer it. He had found his sacred mountain, after all, and the spiritual practice he’d spent much of his life “searching, searching” for. He had no more reason to wander.