In the Presence of My Enemies: Memoirs of Tibetan Nobleman Tsipon Shuguba

Sumner Carnahan with Lama Kunga Rinpoche

Santa Fe: Clear Light Publishers, 1996.

237 pp., $24.95 (cloth).

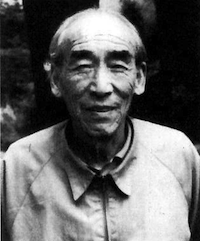

Tsipon Shuguba was the finance minister of Tibet in the Dalai Lama’s government prior to Chinese rule. Captured during the Chinese takeover in 1959, he endured nineteen years of imprisonment, and—perhaps even more painful—knowledge of the catastrophic occupation and destruction of his country: relentless execution, massacres, the bombing and dynamiting of over 6,000 monasteries into rubble. Once part of a wealthy and noble family, Tsipon Shuguba suffered the dissolution of his clan, the deaths of his wife and daughter, and the virtual extinction of his culture as he knew it. Finally “rehabilitated” and released in 1978, he emerged from prison into a Tibet now flooded with Han Chinese settlers and thick with PRC military enforcements, into a Lhasa teeming with Chinese bicycle shops and noodle stands, where no Tibetan has much of a chance of education, job opportunity, or personal safety. A prisoner and a minority in his own land, Shuguba was finally able to immigrate to the United States, where he spent his last years at the home of one of his sons, Lama Kunga Rinpoche, founder of a Tibetan Buddhist meditation center near San Francisco. He died in 1991 at the age of 87.

Before he died, Shuguba was reunited with Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, three long decades after the fall of Tibet, at which point he was the only one left of the former high government officials. His own simple account is deeply moving: “The Dalai Lama made me pull my chair close. We sat facing each other knee to knee . . . His Holiness had many questions. . . . He told me to write my story, to say the truth about everything, not to try to protect anyone. ‘Do not exaggerate,’ he said, ‘just speak the truth.’” Shuguba complied, in a powerful personal account that has all the more impact for its spare frankness and lack of acrimony.

He is completely blunt about his own youthful excesses and lack of judgment. Made a provincial governor when he was barely twenty, he was given too much power too soon. His lack of experience led him to mismanage a local dispute over land boundaries, after which he was relieved of his position. His glimpses of a vanished culture’s traditions are often entrancing: at his marriage, his mother performed part of a traditional ceremony, placing in his young bride’s hand a wooden bucket full of milk and jewels, mingled with gold and silver ornaments. Meant to ensure both continued material wealth and the future wealth of healthy children, this act inaugurated the wedding festivities, and a monthlong celebration of the union at one of the family’s many country estates.

He is equally blunt and factual in outlining the bitter and often lethal political infighting among various Tibetan factions in the rocky period leading up to the Chinese invasion. In 1947, when fighting broke out between the forces of two powerful Tibetan leaders, Reting Rinpoche (the 13th Dalai Lama’s regent) and the current Regent Taktra, Shuguba was in charge of a large force sent to bring Reting, by force if necessary, from his monastery to house arrest in Lhasa. Shuguba grimly chronicles being shot at by monks of Sera monastery, supporters of the Reting faction, and details the attack on Reting’s monastery stronghold: “We killed 80 monks.” In the end, after further bloodshed on both sides, Reting was captured. He died shortly thereafter in Lhasa—poisoned, many suspected. “Lhasa, dispirited, mourned,” says Shuguba of a capital and of a country shaken internally by “civil war,” even as it was increasingly menaced from without by foreign military might.

All this may offer an unpleasant new perspective for Westerners. There are other revelations of intermonastic infighting and inhumane practices by the Tibetan government, such as punishing a high government official by pressing out his eyeballs. And yet Shuguba also chronicles the tremendous heart and courage of a people, and of a nation slipping inexorably into the deathgrip of their ancient enemy, the Chinese.

In his honest history, faithful to the Dalai Lama’s wishes, Shuguba has given us something infinitely more precious than an idealized view of Tibet: the truth as he knew it, and an invaluable glimpse of history in all its painful complexity. The last entry in his autobiography, written shortly before his death, suggests something of his resignation, exquisite clarity and strength of mind:

My hands look as if they belong to someone else, bent and elongated. . . . I am certainly old enough to die. . . . It is night. I am alone with the silence. I begin my prayers.