I stammered as a child and had special difficulty when we had to go around the room in school and introduce ourselves. I would become intensely anxious, rehearsing my name to myself in anticipation of my turn to speak, and then have to push against some invisible force in order to get my well-rehearsed words out. When I was 9 years old, I was mercifully helped by a speech therapist my parents found for me who distracted me with board games while telling me stories of grownups who stuttered worse than I did. She once mentioned a man who couldn’t make a w sound and would therefore never introduce his wife as his wife. The w’s can be particularly difficult for some people, she explained. I knew this to be true and was comforted by the knowledge that I was not alone in my affliction. I felt sorry for this poor gentleman and hoped that a similar fate would not befall me.

Mrs. Stanton, the speech therapist, taught me to distract myself with secret movements nobody could see or with tiny adjustments in the words I used. If I lifted my foot and placed it down hard on the floor just before I had to say something, I was often able to speak more easily. Or if I said “My name is Mark” instead of simply saying “Mark,” my words would somehow flow more gracefully. I learned to anticipate the approach of a difficult word and adjust myself at the last minute. Like a basketball player going in for a layup who avoids a block with a sudden underhanded movement of the ball, I became reasonably adept at getting around myself. By the time I was in seventh grade, I could successfully hide the internal battle that had long bedeviled me. I don’t think anyone ever suspected that I was still afflicted, silently, long afterward.

I wonder how much this childhood issue conditioned my attraction to Buddhism and motivated me to become a psychiatrist. Certainly, those early conversations with my speech therapist gave me the confidence that impediments like mine could be successfully treated with help from an expert. And the techniques Mrs. Stanton taught me bear some relationship to the mental training that is an essential aspect of Buddhist thought. In teaching me to change my approach to my difficulties, she was introducing me to the power a trained mind can have over its everyday anxieties. When I discovered meditation in my young adulthood, this was something I grasped right away. I did not have to be at the mercy of myself. With a slight adjustment in how I related to a challenging situation, I could have an easier time.

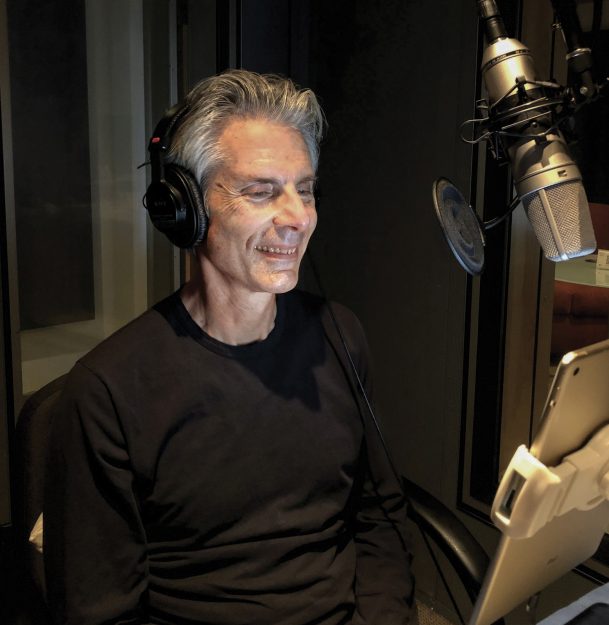

While my stammering became invisible to the outside world, I continued to be aware of it. The trauma of saying my name in the classroom never entirely left me. Some time ago, after my book Going to Pieces without Falling Apart was published, I went to a sound studio to record its audio version. I was asked to sit with headphones in a tiny, soundproof, air-conditioned telephone booth-like box. An engineer sat outside the glass walls monitoring me, and I was instructed to read the book as perfectly as I could, without rustling or coughing, speeding up or slowing down, or messing up in any way. I had done this once before with a previous book, and I was proud of having accomplished it smoothly. It had taken at least two full days and was like a meditation in itself. I had to be still and concentrated and alert to the meaning of my own words and read as well as I could in order to avoid endless retakes. I remember that first engineer telling me I had done as well as Vanessa Redgrave, who he said was a real pro. Needless to say, his praise made me proud.

On this occasion, however, my old speech impediment came back to haunt me. Going to Pieces begins with the word “In”—a strange sound, when one isolates it and stops to think about it and convinces oneself that it cannot be said. In its own way it is as difficult a sound as the w Mrs. Stanton had warned me about. I sensed right away that I was going to have a problem. The ih sound, like the first vowel in “England,” was sticking in the back of my throat. “In the Zen tradition of Buddhism there is a story of a smart and eager university professor who comes to an old Zen master for teachings,” the book begins. I could not figure out how to get the first sound out of my mouth. Ordinarily, if I found myself stuck like this I would just change the wording a little bit. My habit of tricking myself was by now so ingrained that I could do it instantaneously. I might begin with “There was once a smart and eager university professor,” for example, if I felt a similar difficulty approaching.

Here I was reading about going to pieces, and I was falling apart.

But in this situation I could not change the words. I had written them and I had to be faithful to my own language. I glanced to the top of the page to see if there might be an alternative in the chapter title: perhaps I could back up a little and start there. But the chapter title read “Introduction.” That word began with the same exact sound and offered me no help. I tried the motor distractions my speech therapist had taught me. I lifted my foot and jammed it down on the floor. I slapped my left wrist lightly with my right hand. Nothing worked. Boxed in by my own words, I settled back, my rising anxiety leavened by the inescapable irony of my predicament. Here I was, reading about going to pieces, and I was falling apart. I remembered the material of my book, how it counseled the virtues of not always being in control. I tried watching my breath, being mindful of my posture, sending thoughts of lovingkindness to the engineer. But it was getting warmer and warmer in the air-conditioned booth, and the silence was deafening. Finally I heard a voice coming through my headphones.

“Dr. Epstein?” the voice intoned softly. “Is everything all right in there?”

The engineer’s voice shook me. I saw myself as I feared he must see me: the Buddhist psychiatrist, knotted up in the glass booth, a whole book stretching out before him. There would be no Vanessa Redgrave comparisons today. I was on my own.

I sensed how anticipatory anxiety was compounding my problem. When I go to the doctor to have my blood pressure checked, the same thing happens. In trying to be relaxed, I inevitably manage to sabotage myself. I get nervous that the reading will be high, and then my heart starts beating rapidly and my blood pressure does indeed go up, even if I try my best to meditate. I had to buy a home monitoring device in order to convince my doctor that my blood pressure was not always so elevated.

Something similar occurred in the audio booth.

“I’m fine,” I said weakly, trying to be as reassuring as possible to the engineer. “I just need another minute.”

I tried to meditate, relax, exhale, and pay attention, but I knew I was stuck. The opening word would just not come. I had exhausted all my strategies; it was as if I were back in the second grade. I closed my eyes, contorted my body, and somehow forced myself to begin, much as I used to do when I was young. It was like jumping off of a very high diving board for the first time. In this case, the pressure mounted—I was in extreme discomfort, I pushed against myself, something gave way, and the words started to flow. Luckily, there was no embarrassing video recording of my efforts, and once I got over this hurdle the rest of the reading went fine.

It has taken me a long time to figure out what the teaching was in this situation. Upon reflection, the very story I had so much trouble reading shed some light on it. An elderly Zen master pours a cup of tea for a smart and eager young university professor but keeps on pouring even after the cup is overflowing.

“A mind that is already full cannot take in anything new,” the master explains. “Like this cup, you are full of opinions and preconceptions.” In order to find peace, he teaches his visitor, he must first empty his cup.

One of the things filling my mind that day was the image of myself that I wanted to present. As an author and, especially, as a Buddhist psychiatrist, I wished to appear relaxed, open, flexible, friendly, competent, and smart. I wanted to read like Vanessa Redgrave and come off as an accomplished practitioner of meditation. Like everyone else, I have an ego that needs affirmation and an image I am conscious of projecting. Stammering, which frustrated and confused me from an early age, did nothing good for my self-esteem. I had worked hard to overcome it and had assumed the identity of someone who had, to some degree, mastered himself. But the audio recording brought back my youthful difficulties. As mindful as I had learned to be, I was still not cured.

Loss, disgrace, blame, and pain were all nestled into this little episode, but I did not give them the last word.

The Buddha once spoke of what he called the eight worldly winds. Gain and loss, fame and disgrace, praise and blame, and pleasure and pain spin the world, he said, and the world spins after them. These eight winds blow through everyone’s lives, no matter how much we have meditated or how accomplished we have become. They challenge us endlessly: we instinctively recoil from the discomfort they create yet chase after the ego gratification they promise. The Buddha suggested that this ties us unnecessarily to the vagaries of worldly life. The eight winds come and go ceaselessly; as much as we try to pick and choose among them, it is impossible to have some without the others. While we cannot stop them, with enough foresight we can learn to relate to them differently. Desirable things do not have to beguile the mind, and undesirable ones do not have to bring endless resistance. We can let the winds blow through us instead of letting them buffet us about.

Meditation failed me that day in the recording studio. Did the fault lie with me or with meditation? It seemed important, at first, to find someone or something to blame. If I were a better meditator, I reasoned, I would not have had such a difficult time. Or if meditation were more powerful, I would not still be so afflicted. I noticed, however, that these thoughts died down rather quickly. I did not remain obsessed with them. While my ego took a hit—I was not able to present a perfectly unassailable version of myself—finding that my ancient self was still a part of me was perversely enlightening. As stuck as I had become, I still rather enjoyed the humor of my predicament, at least in retrospect. That is much more than I could have said when I was young. Loss, disgrace, blame, and pain were all nestled into this little episode, but as uncomfortable as they made me, I did not give them the last word.

Meditation did not save me the way I might have wished, but maybe its agenda was different from mine. In emptying my mind of blame, I found something I had not anticipated. There, in the bottom of my cup, was some much-needed compassion for the young boy I had once been and, in some way, still was.