BEFORE AUGUST 29, 2005, New Orleans was humming along like any other major, if dysfunctional, American city. If your refrigerator stopped working, for example, you could open the Yellow Pages and choose from a dozen names. After a

On our third day home, I was sweeping broken glass in the hallway when I saw our cordless phone sitting on top of the Yellow Pages. The phone was dead, the city still without power, gas, or water. We were living like pioneers in our own home. I picked up the musty directory and turned the pages with a kind of awe. I knew that, from A to Z, every single listing represented a person or business that was no longer there—thousands of people’s blood, sweat, and dreams, all gone. The buildings were boarded up, their interiors covered with dry muck, the streets deserted for more square miles than you could imagine. It was a visceral realization: Even civilization is impermanent. Not in the future, but now. Its impermanence is now.

Again and again, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, I found my conceptual models bumping up against a reality that would not support them. We tell ourselves stories about who we are and what life is, but they are inherently fictions. They restrict our attention to a narrow band of consciousness within the vastness of awareness, turning reality into a kind of two-dimensional backdrop, a mere stage on which to enact our lives. How shocking it is, then, when the stage declares that it, too, is alive, and proceeds to burn and flood and disappear beneath a field of weeds.

For a month, my wife, Shannon, and I heated water outside on a propane burner and lugged steaming pots of water through the house to bathe and cook. It was time-consuming, but not a problem. The work provided clarity. It communicated to our bodies all the ways the vast infrastructure of civilization normally supports our lives, usually as invisible to us as the workings of our own cardiovascular system, until something goes wrong. We came to appreciate that water is not minted at the tap. I remember, after our gas service had finally been restored, the first time hot water poured into the bathroom sink. Let me tell you, I was awake for that moment. I did not take it for granted. I was aware of the pipe that delivered the water from the heater in the basement, and of the freshly lit flame under the tank, and of the natural gas that ran through a pipe to the valve outside. I was aware of the society beyond our walls, too, now lurching back into existence, that had finally managed to deliver this blessing, hot water on demand. And I recognized that all of this information is available every time I turn the handle; I’m just too engrossed in my own story to notice. My story keeps me narrowly focused here on the ground floor, while all along the water heater is blazing in the basement and birds are wheeling in the sky above.

NOBODY WOKE UP on the morning of August 29 thinking they would die that night in their attic. How shocking and horrifying it must have been to find your story end like that. Few of us can envision the exact circumstances of our death, or how the karma we create today might shape it. But when a million lives are profoundly changed in the course of a single day, you get a sense of the impersonal forces that exist beyond our imagination. They are unimaginable because they are real.

For those people whose lives did not end, the story continued. The event was quickly assimilated into personal narratives about suffering, loss, tragedy, race, poverty, luck, good fortune, adventure, and so on. Connections were made and meanings spun as Katrina was woven into the fabric of a million different lives, tailored to suit a million different stories, each with an individual imagination at the center. This is the way the human mind works: The impersonal is made personal. Sense is added after the fact. The real becomes a story. The story I told myself was one of adventure and good fortune. Our house had largely been spared. Some friends lost their houses, but they were insured, so they’d be okay. No one close to us had been hurt in the storm. And our neighborhood was coming back, bustling with activity, while only two blocks away the floodwaters had left a kind of Dead Zone, mile after mile of empty houses bisected by crusty brown lines where the water had sat. The water lines climbed higher and higher as you moved back toward Lake Ponchertrain and the 17th Street Canal. It was an extraordinary experience to live on the border of such a desolate landscape, the strangeness heightened by the nightly presence of heavily-armed National Guardsmen rumbling down our street in their Humvees.

We hungered for “normalcy.” The first stirrings of it returned to a long and narrow swath of town that people called “the Island”—the curving band of high ground along the Mississippi River that had not flooded. Here you saw homeowners piling debris at the curb, work crews cutting up fallen trees, shops beginning to reopen.

Over the next several months, it became clear that those of us on the Island shared more than high ground. They also shared a point of view. I was fascinated by how people’s opinions on different issues (where to rebuild first, whether to have Mardis Gras, and so on) were largely determined by where they lived. It’s only natural that self-interest shapes our perceptions, I thought, but these people couldn’t even hear the other guy’s side. It was like different sets of values had been issued for different addresses.

For example, I was explaining to my friend John, whose house had flooded, why the city had no choice but to shrink its footprint. It seemed perfectly clear to me that the city simply could not provide services to all of the devastated areas. I was ticking off the usual cogent points about schools, mail delivery and garbage pickup, when he looked at me and said, “Erik, you’re talking about my house.” His house. The lovely first home that he and his wife, Bridget, had saved for years to buy, the house I’d helped them move into only months before the storm. I was moritified. I’m one of those people, I realized.

Mortification presently gave way to curiosity. As a Buddhist, I recognize an opportunity for practice when I see it. Investigating my “smaller footprint” leanings, I observed that, while entirely reasonable, they were also laced with self-interest. (Guess what? A shrinking city means higher real estate values for some.) What fascinated me most was not the revelation that I could be selfish—that’s not news—but the way I had discounted the impact of selfishness on my opinions, thinking something like “Well, sure, I’ll benefit from this, but that’s not the reason I’m for it.” Oh yeah? Try standing in the other guy’s shoes: your opinions might change in an instant.

Does this kind of doublethink sound familiar? It’s how countries are led into wars. It’s how corporate profits are maximized. It’s how we navigate our days. We tell stories about who we are and what life is, but seldom see that they’re only stories. The good news is that the truth is never far away. It’s right here, in fact, posing as backdrop.

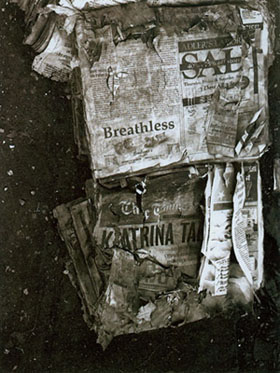

So I decide to get off the Island—which isn’t an island, of course, but just my street, connected by a few minutes’ drive to other streets, neighborhoods still dead almost one year after the storm. I want to see how my own personal “Katrina aftermath” stacks up against reality. Inevitably, my mind has compressed the disaster into a few emblematic fragments, snatches of imagery and feeling, but reality lays it out again, surprising me as it always does.

Twelve flooded houses face their neighbors on either side of a deserted street, their doors left strangely, trustingly open, revealing shadowy glimpses of the ruins inside. Does that do it justice? Did you see them? Did you see inside the bedroom window, the ceiling tiles on the mattress? The crucifix dangling from the mirror? The torn pennant on the wall, Go Holy Cross Tigers! Did you see the bright green lizard on the fallen fence outside or the overgrown weeds? No? Not yet? What can I add to make this place real to you, not just a story? The muck-covered photo album in the gutter? The woman’s shoe filled with dirt and leaves? A child’s orange ball suspended in the branches of a dead tree?