A lama I used to study with once said he didn’t understand why people would listen to recordings of Tibetan chanting. “That,” he said, “would be like watching someone else eat a meal.”

That’s precisely the challenge of Into Great Silence, Philip Gröning’s respectful documentary on the ultra-austere lives of Catholic Carthusian monks at the Grande Chartreuse monastery in the French Alps. How can film, which by its nature shows the outer surfaces of things, convey the experience of men who have have taken a vow of near-total silence and wholly devoted themselves to the inner life?

That’s precisely the challenge of Into Great Silence, Philip Gröning’s respectful documentary on the ultra-austere lives of Catholic Carthusian monks at the Grande Chartreuse monastery in the French Alps. How can film, which by its nature shows the outer surfaces of things, convey the experience of men who have have taken a vow of near-total silence and wholly devoted themselves to the inner life?

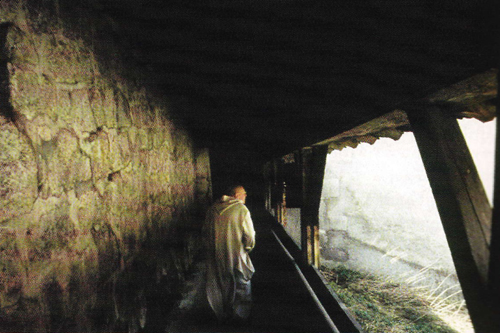

Into Great Silence comes closest to this goal in several poetic low-light sequences, speckled with optical noise that almost palpably suggests the spiritual presence sparkling through simple objects and routines. Gröning might well have been thinking of the great Christian poet and mystic Gerard Manley Hopkins, with his sense of the divine presence as an all-pervasive electricity: “The world is charged with the grandeur of God.” Certainly the film doesn’t try to finesse the problem through verbal explanation. In keeping with its title, it is almost entirely wordless, as it follows the monks through their days and seasons of silence and solitude: kneeling in motionless prayer in their individual cells, walking in twos or threes down a long, vaulted white stone corridor in their white hoods and robes, sawing firewood, digging snow from seedbeds and later planting and watering the vegetables. Inanimate objects are as eloquent in their silence as the humans: water droplets gathering at the lower edge of a just-washed bowl, the single red candle in the darkened great room in which hymns are sung through the night, even the twice-glimpsed white jetliner—a strange emissary from the outside world, so high overhead that it makes this world feel even more remote.

We are pulled so powerfully and so rhythmically into this silent world—to suggest a lifelong commitment to monastic routine, Gröning makes liberal use of repetition, returning again and again to the same kneeling monk or the same red candle—that the rare instances of talk are shocking. Before the assembled brotherhood, two novitiates are formally inducted into the order (“What do you ask for?” “Grace”). Near the end, an elderly monk with extravagant eyebrows like gray weeping willows explains why his closeness to God makes him unafraid of death and even grateful for his blindness. The elders of the community enjoy their prescribed Sunday walk, where they indulge in high-spirited gossip concerning the practices of neighboring monasteries, clucking their tongues over the order that sets out six wash-basins before the meal instead of just one (imagine!). When a grizzled monk loudly calls a missing cat to its dinner, his voice feels so raucous we want to shush him.

Gröning does use words in another way, occasionally filling the screen with passages from the texts that guide these men’s lives, rhythmically repeating these as well: “Anyone who does not give up all he has cannot be my disciple”; “Behold the silence, allow the Lord to speak one word in us, that he IS”; and, most insistently and hauntingly, “O Lord, you have seduced me, and I was seduced.” If you’re reading this magazine instead of, oh, watching TV, you probably know something of that seduction. Hindus have a lovely metaphor for it in their stories of Lord Krishna, whose skin is blue because he embodies the sky-like vastness of the infinite. He’s the rock star god, perpetually twenty-three years old, roaming the countryside, playing the siren song of enlightenment on his silver flute, seducing all the local milkmaids, or gopis. (Nowadays we call them groupies.) Of course, we are gopis, and once we’ve heard that song it’s hard to take any other very seriously.

Gröning does use words in another way, occasionally filling the screen with passages from the texts that guide these men’s lives, rhythmically repeating these as well: “Anyone who does not give up all he has cannot be my disciple”; “Behold the silence, allow the Lord to speak one word in us, that he IS”; and, most insistently and hauntingly, “O Lord, you have seduced me, and I was seduced.” If you’re reading this magazine instead of, oh, watching TV, you probably know something of that seduction. Hindus have a lovely metaphor for it in their stories of Lord Krishna, whose skin is blue because he embodies the sky-like vastness of the infinite. He’s the rock star god, perpetually twenty-three years old, roaming the countryside, playing the siren song of enlightenment on his silver flute, seducing all the local milkmaids, or gopis. (Nowadays we call them groupies.) Of course, we are gopis, and once we’ve heard that song it’s hard to take any other very seriously.

The question is, how far will we go to follow it? That’s the real challenge of this film: to see the lives of men whose total commitment to practice makes the little set-it-and-forget-it daily sessions on our cushions that many of us call a spiritual path look pretty measly.

I’ve been to one professional basketball game in my life, Bulls vs. Nets at the Meadlowlands during the golden era of Michael Jordan. Having previously watched the games only on television, I was shocked to see the crazy-pinball electronic display on the big scoreboard every time there was a pause in play, and the assorted clowns and jugglers and dancing dogs that were trotted out during halftime; even as I walked across the parking lot at game’s end, it was to the strains of the Nets’ theme song, blaring over scratchy, lo-fi speakers, as if any break in this evening of constant stimulation might leave us doubting whether we’d had a good time. My point is, we’re so acclimated to a world of stimulation that it’s easy to congratulate ourselves on taking half an hour a day to put down our iPods and newspapers, to stop checking our email and just sit. Carthusian monks have committed to a life that is precisely the opposite, a life of minimizing stimulation. They’re serious, and getting a taste of their lives provides a useful benchmark against which to check our own seriousness. At two and three-quarters hours, Into Great Silence is a long film about nothing happening; it’s shocking to realize that the film’s entire running time is what, in real time, a monk might spend in one kneeling prayer session. (A few folks in the audience couldn’t handle the tedium and walked out, and the lack of dialogue presented no cover for the snoring of the guy in the row behind me.)

I’ve been to one professional basketball game in my life, Bulls vs. Nets at the Meadlowlands during the golden era of Michael Jordan. Having previously watched the games only on television, I was shocked to see the crazy-pinball electronic display on the big scoreboard every time there was a pause in play, and the assorted clowns and jugglers and dancing dogs that were trotted out during halftime; even as I walked across the parking lot at game’s end, it was to the strains of the Nets’ theme song, blaring over scratchy, lo-fi speakers, as if any break in this evening of constant stimulation might leave us doubting whether we’d had a good time. My point is, we’re so acclimated to a world of stimulation that it’s easy to congratulate ourselves on taking half an hour a day to put down our iPods and newspapers, to stop checking our email and just sit. Carthusian monks have committed to a life that is precisely the opposite, a life of minimizing stimulation. They’re serious, and getting a taste of their lives provides a useful benchmark against which to check our own seriousness. At two and three-quarters hours, Into Great Silence is a long film about nothing happening; it’s shocking to realize that the film’s entire running time is what, in real time, a monk might spend in one kneeling prayer session. (A few folks in the audience couldn’t handle the tedium and walked out, and the lack of dialogue presented no cover for the snoring of the guy in the row behind me.)

But does seriousness, in the form of austerity, correlate directly with spiritual progress? Are these monks getting the juice? For me, that’s the real mystery. Watching them pray their long, silent prayers in what look to be excruciatingly uncomfortable wooden pews, the friend who saw the film with me commented, “They look like they’re trying too hard.” When the novitiates are welcomed into the order, they’re told they’re entering a life of “everlasting peace and joyful penitence.” Again, it’s impossible to judge from the outside, but, frankly, it doesn’t look so joyful. This is not a matter of Christian or Buddhist theology, but of skillful or unskillful practice. There are plenty of Buddhists who try too hard, and there are plenty of skillful meditation tips in the Gospels: Jesus’s exhortation to “be as alert as serpents and as simple as doves” is about as precise a pith instruction on meditation as we could ask.

But does seriousness, in the form of austerity, correlate directly with spiritual progress? Are these monks getting the juice? For me, that’s the real mystery. Watching them pray their long, silent prayers in what look to be excruciatingly uncomfortable wooden pews, the friend who saw the film with me commented, “They look like they’re trying too hard.” When the novitiates are welcomed into the order, they’re told they’re entering a life of “everlasting peace and joyful penitence.” Again, it’s impossible to judge from the outside, but, frankly, it doesn’t look so joyful. This is not a matter of Christian or Buddhist theology, but of skillful or unskillful practice. There are plenty of Buddhists who try too hard, and there are plenty of skillful meditation tips in the Gospels: Jesus’s exhortation to “be as alert as serpents and as simple as doves” is about as precise a pith instruction on meditation as we could ask.

Austerity can be an indulgence, a false refuge, as much as sensuality. Shakyamuni tried both and rejected both, pointing to the Middle Path that is all that’s left when these two are renounced. I think the Middle Path is often misconstrued as a lukewarm compromise, a sort of shrugging resignation that goes with middle age. In fact, the Middle Path is the most relentless, on-your-toes, moment-to-moment challenge imaginable. Without falling into the sleepy routine of pleasure-seeking, without falling into the potentially equally sleepy routine of world-denying and ritualized God-seeking, can you wake up to each moment’s encounter with whatever comes along, just as it is?

The film comes closest to addressing that question in its most uncharacteristic sequences. In a departure from his usual candid, nonintrusive observation of the monks going about their lives, Gröning occasionally cuts to obviously set up, mercilessly lit, full-face closeups, in which each monk gets a long half minute or so to gaze directly at the camera. Weirdly reminiscent of Warhol’s Screen Test films of Bob Dylan, Allen Ginsberg, Edie Sedgwick, and others, they set the same ruthless exam—to just sit and just be, to be who- or whatever one is, deprived of the usual props and plots. Nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. Some of the monks shift their gaze uncomfortably, some gulp or blink, some gaze steadily, some may or may not be trying too hard. As we gaze at them gazing, trying to fathom whether they’ve squeezed some measure of realization from their hard path or merely squandered their lives in a sterile struggle, we might also wonder how we would fare in such a screen test.

♦

Into Great Silence

Philip Gröning, Director

Zeitgeist Films, 2006