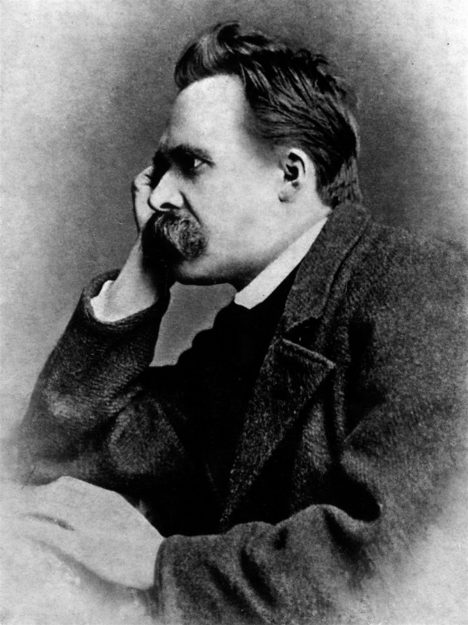

When regrets about my failures and misfortunes begin to overwhelm me and my life feels disappointing, I have learned to seek guidance from two of my spiritual heroes, the Zen master Taizan Maezumi Roshi (1931–1995) and the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900). Maezumi Roshi once responded to my expressions of remorse for opportunities lost as he had to many other practitioners at the Zen Center of Los Angeles. Smiling gently but unable to resist the urge to tease me, he said that I had so far failed to appreciate my life. “Please encourage yourself,” he had also written, “so that your practice is fully to appreciate this transient, frenzied life as the whole self-contained, self-fulfilled life.” And Nietzsche, whose suffering and loss were exponentially greater than mine, came to believe that the ultimate challenge in life is amor fati, to love your fate. Think of “fate” here as the simple, unchangeable “given”: what simply is, whether we like it or not. For Nietzsche, self-pity, disabling regret, and disappointment that reality is the way it is or that the past was what it was were clear signs of spiritual weakness. In Ecce Homo, he writes: “My formula for greatness in a human being is amor fati: . . . not just to bear the given, the necessary, still less to conceal it . . . but to love it.”

Excellent advice from both Maezumi and Nietzsche, but without serious reflection, I would have probably responded by saying something like, “Oh, sure. Of course I appreciate my life. There have been amazingly good times, times of plentitude and peace, times of friendship, love, and laughter. I reflect back on these with gratitude and appreciation.” But this response wouldn’t have satisfied these two contemplative spirits. Maezumi would most likely have sighed in loving disappointment; Nietzsche would have scowled in open condemnation. They hadn’t exhorted me to appreciate and love only the good things in life—the pleasures, successes, and victories. They had challenged me to appreciate the whole mess—pleasant and painful—and to love what can’t be changed, no matter how debilitating it has been. They had directed me to love it all, the good, the bad, and the ugly, because there it is: reality, staring me in the face.

But is that feasible—to love and appreciate my injuries and sicknesses, my humiliating weaknesses, my dishonesty, greed, and egocentricity, and the numerous acts of cowardice by which I have hidden all this from everyone? Am I somehow to love everything I should have done but didn’t, everything I shouldn’t have done but did? I cringe every time I bring any of that to mind. Even though I would prefer to be oblivious to all of these weaknesses of character and pretend that they don’t exist, they frequently come unbidden to mind, often accompanied by a growing sense of disappointment. Regrets, guilt, and shame don’t necessarily outnumber the successes, pride, and pleasures in my life, but they do weigh more heavily on me.

So if Maezumi and Nietzsche meant loving the whole of my life, including the humiliating failures of spirit, the challenge is magnified enormously. But why should I appreciate the unappreciable? Why even attempt to love the seemingly unlovable dimensions of my past, my character, and whatever life has doled out? Even if this demand were intellectually plausible, it would still strike me as viscerally unpalatable. But taking their admonitions seriously, given my respect for these two insightful teachers, I realize that what they were teaching was their realization that spiritual depth and human shallowness are inseparable. They are always found together.

If we have imagined that the great Zen master and the world-renowned philosopher didn’t face excruciating failures and setbacks or experience suffering or make mistakes as we have, we would be dead wrong and would have missed the point of their teachings. In fact, the tales of woe in these two lives approach tragic dimensions. They both faced extreme hardship, suffering, even humiliation, but in visionary moments, they broke through to the other side of these difficulties, tapping into an enormous reservoir of personal power. In that awareness, they witnessed the magnificent beauty of all life just as it is, encompassing, as it does, inconceivable difficulties, hardships, and challenges. They experienced the miracle that this present reality has unfolded precisely as it has.

The crucial point is this: Because we are finite beings, pain, failure, and depression are inevitably woven into the very fabric of our lives. To accept that basic fact is to finally come to terms with what it means to be human. This fundamental self-acceptance is the basis of self-respect, and self-respect is the seed and substance of an awakened life. Because the past is what it is and, as a result, I am who I am, my task is to embrace the whole of my life without denial or revulsion. Lacking that level of self-integration, I’m not really working with who I am, thereby disabling the only chance I have to make skillful, transformative moves in life. As both Nietzsche and Maezumi knew, the most vibrant individuals are those who have learned to smile upon all aspects of their experience with open, honest inclusion.

Recognizing who you are and learning to be at ease with it is the essential, nonnegotiable point of departure for any greater profundity in life. It is only through a disciplined integration of all dimensions of our past that we learn to work through the problems that have been so disabling and, on that basis, to work creatively with the world. Nietzsche called this reintegration of the past “knowledge acquired through suffering,” and it’s what Buddhists contemplate in their meditations on human suffering. These practices demand unflinching honesty, a level of truthfulness and openness about our lives that is not easy to acquire. The Perfection of Wisdom sutras upon which Maezumi’s Mahayana Buddhism was founded stress the idea that the capacity to tolerate the truth about oneself and the world—to set aside self-placating delusions and face the way things really are—is absolutely essential to the awakening of freedom in life. Nietzsche frequently wrote that one measure of spiritual strength is how much truth you can bear. Being able to maintain a courageous inner dialogue between successes and failures, joys and suffering, strengths and weaknesses requires the capacity to face the truth and to gather all aspects of your life into an intelligible whole. Love the truth, Maezumi and Nietzsche seem to be saying, whatever that is, because the truth will set you free.

This truth about my life includes far more than my own choices and decisions. It also encompasses aspects of my life that I had no role in creating—the imprints of family, community, culture, language, and the long and complicated history of our species. All of this just happened—it is my fate or destiny. It includes accidents that have befallen me, humiliations and suffering that have come my way through no particular fault of my own. We must somehow embrace not only what we did or didn’t do but also what’s been done to us and what simply happened for whatever reasons. To regret or deny or resent any part of this is what Buddhists call delusion. Maezumi and Nietzsche exhort me to embrace it all as the essential content of my life—not just to accept it but to appreciate and love it.

With that in mind, we can see that what both Maezumi Roshi and Nietzsche were pursuing was something much larger than just appreciating or loving their own individual lives. What they both aspired to appreciate and love is life itself, the agonies and the sublimities of all living beings. For Maezumi, this is the basis of the bodhisattva’s vow to absorb the suffering of all sentient beings and take the challenge to redeem it, to make it right. Maezumi called this “wisdom sought for the sake of everyone.” Beyond the Zen master’s own personal awakening, then, is the depth dimension of that goal—the awakening of their community, of the entire species so that all human beings might participate in the creation of a new world. By extending their sense of responsibility as far as possible beyond their individual lives, Maezumi and Nietzsche imagined themselves embracing all humanity and all life. And they aspired to do this not just in thought and intention but in everything they do.

Still, I wonder how to go about loving what I quite honestly don’t love. Where do I even begin? Nietzsche suggests the answer in a paragraph in The Gay Science entitled “One must learn to love.” He starts with our love of music, showing how that love wasn’t simply innate but was cultivated over long stretches of time through much listening. We listen repeatedly until the music becomes part of us. And it is not just love of music that is acquired this way, Nietzsche says. We had to learn to love everything we now love through patience and discipline until gradually a space opens within us for that new love to reside. “There is no other way,” he tells us. “Even love has to be learned.” Even the love and appreciation of oneself. So Nietzsche challenges himself: Amor fati—to love the given, what cannot be changed. “Let that be my love from now on,” he writes. “Someday I want only to be a Yes-sayer.”

Becoming a “Yes-sayer” means affirming all past and present reality as the necessary starting point for creating a new future. But how is this affirmation to be accomplished? Through practice, Maezumi Roshi says. Daily, focused, mindful practice of mental-spiritual disciplines specifically designed to enable embracing reality as it is, without excuses, avoidances, or delusions. Embracing it fully allows us to work with it by bringing all positive powers at our disposal to bear on it: presence of mind, attentiveness, energy, kindness, patience, courage, generosity, wisdom, compassion—and finally, love. These can be learned, and even if this aspiration feels like it’s too far beyond us, for Maezumi and Nietzsche, the path of that transformative learning is simple and right here where we already are: Carefully designed intentions. Daily practice. Simple steps. Just do it.

The joy of waking up to who and where you are—and loving it—is an ecstatic experience of freedom.

Although in his era Nietzsche’s culture lacked the explicit and highly sophisticated practices of interior transformation that Buddhists had been developing for over two millennia, he had mastered the essential formula—“long practice and daily work”—and attempted to apply it in his own way. Nietzsche called this kind of self-discipline “a rare and great art” and knew from experimenting with his own life that through the everyday practices of self-acceptance and self-sculpting, human beings could “experience their most exquisite pleasure.” This pleasure, the joy of waking up to who and where you are—and loving it—is an ecstatic experience of freedom. So when Nietzsche asks himself “What is the seal of having become free?” he answers, “No longer to be ashamed before oneself.” That’s saying it plainly: the “seal,” or sign of freedom, is that you have learned to love your fate, to appreciate your life, and by pushing through debilitating shame, to tap into the selfless energy of openhearted living.