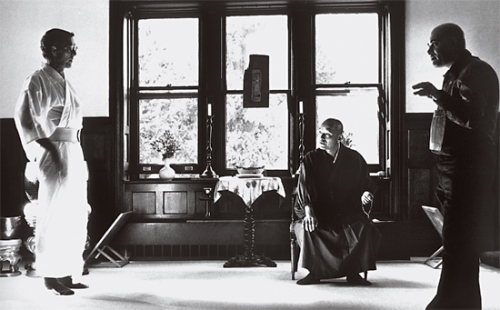

In 1982, Peter Matthiessen traveled to Japan with his teacher, Bernie Glassman, to pay respects to the masters in their Zen lineage. Matthiessen, a two-time winner of the National Book Award, chronicled their pilgrimage in Nine-Headed Dragon River: Zen Journals 1969–1982. A new book, Are We There Yet? A Zen Journey Through Space and Time (Counterpoint, 2010, 160 pp., paper, $29.95), takes Matthiessen’s account of that trip from Nine-Headed Dragon River and places it next to photographs shot by Peter Cunningham, who was also along for the ride. It’s a stellar combination. Matthiessen’s luminous prose, which sheds light on both their pilgrimage and important historical Zen figures, is made even more enlightening by Cunningham’s stunning black-and-white images. With its emphasis on ancestors and lineage, Are We There Yet? is a deeply reverent work that will appeal most to readers with a serious interest in Zen in the West. The book includes an introduction by Bernie Glassman and an afterword by Matthiessen’s dharma heir, Sensei Michel Engu Dobbs.

In 1982, Peter Matthiessen traveled to Japan with his teacher, Bernie Glassman, to pay respects to the masters in their Zen lineage. Matthiessen, a two-time winner of the National Book Award, chronicled their pilgrimage in Nine-Headed Dragon River: Zen Journals 1969–1982. A new book, Are We There Yet? A Zen Journey Through Space and Time (Counterpoint, 2010, 160 pp., paper, $29.95), takes Matthiessen’s account of that trip from Nine-Headed Dragon River and places it next to photographs shot by Peter Cunningham, who was also along for the ride. It’s a stellar combination. Matthiessen’s luminous prose, which sheds light on both their pilgrimage and important historical Zen figures, is made even more enlightening by Cunningham’s stunning black-and-white images. With its emphasis on ancestors and lineage, Are We There Yet? is a deeply reverent work that will appeal most to readers with a serious interest in Zen in the West. The book includes an introduction by Bernie Glassman and an afterword by Matthiessen’s dharma heir, Sensei Michel Engu Dobbs.

The Heart of the Revolution: The Buddha’s Radical Teachings on Forgiveness, Compassion, and Kindness(HarperOne, 2011, 224 pp., paper, $15.99) opens with author Noah Levine likening the Buddha to an outlaw biker. In the same way that outlaws see themselves as individuals who stand outside mainstream culture, Levine sees the Buddha as a radical whose teachings are world-shattering and not for the faint of heart. “The practices in this book are not a quick fix,” Levine writes. “They are a map to a hidden treasure. You will have to do all of the digging yourself.” After years of doing his own digging during meditation practice, Levine—who grew up in the punk subculture— started to experience some of the compassion that the Buddha promised would be found. “My heart has softened; my mind has quieted down,” he tells us. “These days, I rarely want to bash anyone’s head in.” Displaying both Theravada and Mahayana influences, Levine describes practices such as lovingkindness, tonglen, and forgiveness meditation. What’s most praiseworthy about The Heart of the Revolution is that it’s unabashedly pragmatic. As he did in his previous books, Dharma Punx and Against the Stream, Levine makes clear that he doesn’t care about what Buddhism is or isn’t; he cares about what works to make the world a better place. It happens that Buddhism accomplishes this, Levine finds, by giving us access to our innate “aggressive wisdom.” The Heart of the Revolution is a call to action. Jack Kornfield wrote the book’s foreword.

Does a dog have buddhanature? As anyone familiar with koan practice knows, the correct answer to this peculiar question is “Mu.” In the most famous version of the Mu koan, the Chinese master Zhaozhou (Joshu in Japanese) delivered this straightforward response (“Mu” literally means “no”) to a curious monk. Of course, as is true of many things in Zen, the meaning of the koan lies somewhere beyond the verbalized answer. The Book of Mu: Essential Writings on Zen’s Most Important Koan (Wisdom Publications, 2011, 336 pp., paper, $17.95), edited by James Ishmael Ford and Melissa Myozen Black, is a collection of short commentaries by a variety of Zen teachers and scholars, all attempting to unpack the meaning of this famous koan. Many of the contributors agree that ultimately the koan is not about a dog’s buddhanature, dear reader, it’s about yours. “Students working with a koan like Mu have to throw themselves totally into the koan with the whole body and mind,” the late John Daido Loori wrote. “They have to become the koan, losing themselves completely in this Mu. What is wonderful about Mu is that it’s completely ungraspable.” Among the impressive and diverse list of teachers you’ll find in the collection of essays are Eihei Dogen, Robert Aitken, Taizan Maezumi, and Susan Murphy. The Book of Mu is the third book in Wisdom Publication’s “Essential Writings of Zen” series (The Art of Just Sitting and Sitting with Koans, both edited by Daido Loori, are the other two).

Thanissaro Bhikkhu, a monk in the Thai forest tradition and abbot of the Metta Forest Monastery, is a translating machine. We know this because every time he finishes a new translation (or a new book, for that matter), he sends a box of them to the Tricycleoffice. Jealous? You don’t have to be: all of his works are easily obtained, thanks to his belief that dharma teachings should be freely distributed. If you can’t find a bound copy of one of his titles at your local dharma center, you can read many of them online at www.accesstoinsight.org, a website offering texts from the Pali canon and extensive study guides to Theravada Buddhism. The latest title is Inner Strength, an informative collection of talks given by Thanissaro Bhikkhu’s late teacher Ajaan Lee Dhammadharo. A revised edition of a previously released translation, it covers topics from breath sensations to mental power.

It’s easy to feel intimidated by books on spiritual life, even when they’re written in the gentle tones of a gifted teacher calling you to come stand with him or her. Sure, you’ve reached that special place, you might think, but I’m nowhere near as dynamic as you are. Perhaps this is why it’s so encouraging to read Zen teacher Les Kaye’s Joyously Through the Days (Wisdom Publications, 2011, 208 pp., paper, $16.95), about opening up to our inherent sacredness. Kaye comes across as a regular guy who has learned valuable things about what human beings want and is simply sharing this information with readers. You feel as though you can join him—such is his skill in making Zen wisdom accessible. In three sections, Kaye—who worked as a design engineer at IBM for 30 years—explores the dimensions of suffering, daily practice, and composure from a Zen perspective. His objective in writing Joyously Through the Days is, as quoted by Huston Smith in the book’s foreword, “to illustrate how Zen practice enhances awareness, patience, and generosity, and enables us to respond creatively to the complexities, distractions, and uncertainties of modern times.” That Kaye is able to accomplish this goal makes the book well worth reading.