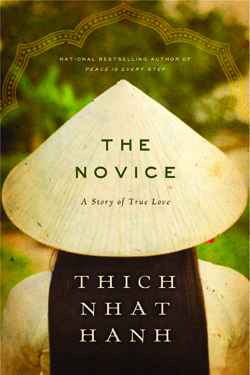

The Novice: A Story of True Love

The Novice: A Story of True Love

Thich Nhat Hanh

HarperOne,

September 2011

160 pp.; $23.99 cloth

What does Thich Nhat Hanh believe? In many of the early writings that launched his reputation in the West, he comes across as a peace activist first, a sort of ecumenical Buddhist sage second, and a traditional Zen master a distant third. Buddhism is mentioned in early books like The Miracle of Mindfulness and Being Peace, but it seems a very relaxed, nonthreatening faith that makes few demands on its adherents. The dharma, he explains, is simply “the way of understanding and love.” The sangha is just “the community that lives in harmony and awareness.” Meditation almost sounds easy, and enlightenment is just a matter of paying closer attention. Practice is essential, but “if you feel at all tired while practicing, stop at once.” And as if to underscore the universal nature of these teachings, his American followers organized themselves under the radically nonsectarian and essentially nonreligious rubric “The Community of Mindful Living.”

To many of the new followers attracted to his writings in the 1980s and 1990s, Thich Nhat Hanh became synonymous with Vietnamese Buddhism, although the traditional Vietnamese temples dotting the landscape of North America and Europe remained largely invisible to all but the exile community. And so the long and storied history of Buddhism in Vietnam was largely lost on Thich Nhat Hanh’s growing readership, which was unfortunate, since it might have helped them put his teachings into context.

Vietnam lies at a unique point in Buddhist Asia, with the Theravada nations of Cambodia and Laos to the west and the Mahayana motherland of China to the north. Many Buddhist traditions permeated the country and to a great extent blended together. The Zen and Pure Land sects had largely merged by the 12th century. Most monks wore robes very similar to those of their Chinese brethren, but generally they lived according to the full rigor of the Theravada precepts. In 1964, the Unified Buddhist Church of Vietnam went a step further, bringing the Theravada and Mahayana traditions—separate for nearly two millennia—under a single umbrella sangha. In his authoritative Buddhism and Zen in Vietnam, Thich Nhat Hanh’s friend the late Thich Thien An quotes a Vietnamese Theravada master proclaiming that there is “no distinction” anymore between Theravada and Mahayana in Vietnam.

Given that Thich Nhat Hanh came of age among those intertwining lineages, in which Mahayana teachings are heavily seasoned with Theravada discipline, it seems natural that he also held some rather orthodox views of Buddhist practice. In Being Peace, he seemed to imagine that Buddhism in the West might evolve into something quite different than that found in Asia, that we would “create [our] own Buddhism.” But in 1997, he published Stepping into Freedom, which presented a much more traditional view of monastic training to his Western audience. No longer was the emphasis on carefully eating each piece of tangerine, as he had memorably described in The Miracle of Mindfulness; now one also had to “chew each mouthful quietly and carefully, thirty or fifty times,” as well as remember to lie on one’s right side whengoing to sleep and “not to moan” when using the toilet. Nhat Hanh published Freedom Wherever We Go in 1999, with the subtitle A Buddhist Monastic Code for the Twenty-first Century. But this code turned out to be a lot like the traditional codes of previous centuries. It was updated to permit riding in cars, for instance, and using email under certain conditions, but it did not revisit the rules of celibacy or recognize the equality of women. (Inappropriate touching of the opposite sex necessitates an apology for a monk, for example, but expulsion for a nun.) Around this time he also reorganized his American sangha into a branch of a reincorporated Unified Buddhist Church, not entirely without resistance.

Thus while some in the Western Zen community and elsewhere have blurred the line between lay and monastic practice, Thich Nhat Hanh seems to have endorsed a decidedly two-track dharma. For the laity, he emphasizes nondogmatic expressions of mindfulness, love, and peace, with few strict requirements beyond basic wholesome living. But for the ordained, it’s the full monty.

The Novice falls clearly into this more regimented side of his teachings. As his long-time disciple Sister Chan Khong explains in a lengthy and somewhat meandering afterword, The Novice is Nhat Hanh’s retelling of a traditional Vietnamese story in which a young woman, Kinh, poses as a man in order to ordain as a novice monk. She endures tremendous hardship throughout her adult life, woefully mistreated and falsely accused at nearly every step. When a local woman— what we would now call a stalker—accuses Kinh of fathering her child, Kinh accepts the baby and raises him in a hut just outside the temple, even though this brings her nothing but further shame. Kinh ensures that the little boy has enough to eat, even chewing his food for him, and sings him lullabies (“using only meditations from the sutras and scriptures”).

The language of The Novice is simple and direct, more that of a parable than a novel. (Which is good, because monks and nuns aren’t allowed to read “worldly novels,” let alone write them.) The teachings are explicit rather than subtle:

People, it seemed, were always allowing jealousy, sadness, anger, and pride to determine their behavior. So much suffering was caused by misunderstandings and erroneous perceptions about one another.

Kinh’s story is briskly told, consuming only about 100 pages of the slim volume. Years can pass by in a few lines. Yet the book slows down at times to ruminate on Buddhist teachings. The subtitle of the novel is A Story of True Love, and several passages explore the question of what exactly “love” means. Again, Nhat Hanh does not hide his own views:

The novice’s deepest desire was to continue practicing as a monastic. This kind of desire is known as bodhicitta, the mind of bodhisattvas, of awakened beings—the mind of love. This is love that contains the spirit of kindness, compassion, joy, and equanimity; it is not a sentimental, tragic, obsessive, or sensual kind of love. To love, according to the teachings of the Buddha, is to have compassion for and relieve the miseries of all who suffer, miseries due to sensual desires, hatred, ignorance, envy, arrogance, and doubtfulness.

Whether this somewhat impersonal compassion should be considered “true love” is something readers may need to decide for themselves. Toward the end of the book, Kinh refuses treatment for pneumonia, even though her death will cost the child the only family he has known. In her final moments, she enters the Concentration of Immeasurable Equanimity in which she “embraced … every being in the world; there was no discrimination between loved ones and enemies.” But can we truly love someone if we also love everyone? What does it mean to love a child without emotional attachment? Although The Novice raises these questions, it does not answer them.

In part because the writing is so direct, The Novice doesn’t hold up as a work of literature. The characters are largely one-dimensional, and their inner lives are described in matter-of-fact prose rather than being illuminated through their speech or actions. Kinh’s ex-husband, we are told, “did not know how to enjoy the gift of living with his loved ones” and “thought only of exams and being a government official.” But he appears in only a few scenes, and most of what we learn of him comes only from such pronouncements. The most interesting character is probably Kinh’s abbot. He is largely spared these overt descriptions, and we are left to imagine him through his conversations with Kinh, which reveal him to be both wise and kind.

And while The Novice has value as a work of teaching, it is not clear what this unusual book adds to the Thich Nhat Hanh oeuvre. Kinh’s near-fanatic devotion to practice may have little resonance with many lay students, for whom escaping family life is not an appealing option. For those readers, there is really no substitute for Nhat Hanh’s much more accessible classic texts. For anyone wanting to understand his view of monastic life, this topic is more thoroughly addressed in Stepping into Freedom and Freedom Wherever We Go.

Did Thich Nhat Hanh’s beliefs really change somewhere between the all-embracing simplicity of Being Peace and the more rigid austerity of The Novice? In retrospect, there were signs from the beginning that his teachings were more nuanced and complex than they may have seemed. Thich Nhat Hanh’s first book, Vietnam: Lotus in a Sea of Fire, published in 1967, discussed Buddhist history but little doctrine or practice, and aimed at ending the Vietnam War rather than spreading the dharma. When his antiwar activities forced him into exile, he became something of an accidental missionary. His little-noticed Zen Keys, published in 1974, was a more traditional collection of Zen Buddhist teachings that includes, among many other fascinating gems, translations of several Vietnamese koans. In its thoughtful introduction by the American Zen master Philip Kapleau, Thich Nhat Hanh appears not as part of the “new American Zen” then emerging but rather as one of our “links with the great Asian traditions that spawned and nourished it.”

Being Peace itself was composed from a series of lectures delivered in 1985 to exactly the sort of new American Zen Buddhists Kapleau had foreseen. After so many years in the West, it is not surprising that Thich Nhat Hanh had begun to emphasize a nonsectarian message that would appeal to that audience. Yet even then, in his discussion of his new Order of Interbeing, for example, there are hints that lay and monastic Buddhism might be quite different. (Recent editions of Being Peace have made this even more explicit.) Thus it’s not so much that Thich Nhat Hanh changed his beliefs as that his recent published work in English has expanded to include a fuller range of his teachings. The sterner ethos of The Novice was, in fact, always present.

In the early 1990s, before his books had propelled him to the status of Buddhist celebrity, Thich Nhat Hanh gave a public lecture at a park in Oakland, California. He had brought a small entourage of sangha members on tour with him, and at one point he introduced two robed Americans, a young man and woman, who had arrived in Thich Nhat Hanh’s community of Plum Village some years prior. Because they were unmarried, the couple had been asked to reside separately in the men’s and women’s dorms. Eventually, Thich Nhat Hanh proudly announced, they had each decided to ordain, and both were still living in Plum Village, now as celibate monastics. They still loved each other, of course, but now they loved everyone else, too.

Whether you find this story touching or slightly horrifying probably says a lot about what you’ll think of The Novice. Here again Thich Nhat Hanh makes the case that true love is not found in the unique bond between two people, but is something we only discover when we discard all such bonds in favor of a deeper connection transcending individuals. His path of total renunciation has clearly brought him true wisdom, yet it is not an example that many in the West are likely to follow. But that’s OK. Others can return to the beautiful opening lines of Being Peace: “Life is filled with suffering, but it is also filled with many wonders, like the blue sky, the sunshine, the eyes of a baby.” We all need to remember that lesson. And Thich Nhat Hanh needs the rest of us to make the babies.