I’d been working as a hospice volunteer for about six years when my friend Nando fell ill. We had been lovers for many years and though we were separated, we were still close friends. And then one day she collapsed, fainted, and was taken to the hospital. It turned out to be leukemia.

First she spent a lot of time at Stanford Medical Center, getting chemotherapy. That period was extremely painful for her. Her chances of survival were low, because she had a pretty rare form of leukemia. But she was really going for it, trying to do anything she needed to do. I remember some horrendous times. I found her once crawling across the room, moaning in pain and dragging this IV stand behind her. She told me, “This is how it is most of the time”—excruciatingly painful.

She sent out fund-raising letters to people, asking for support, trying to gather people around her. We organized a small hospice team to take care of her as she got sicker. We had a twenty-four hour rotation. She wanted as much as possible to be conscious and accepting of the process.

About a month before she died, she decided to have a celebration for her dying. She didn’t want to be dead when it happened. So she invited friends—she had lots of friends—and about a hundred people showed up. I remember her mother and her father came. They had separated a long time before and hadn’t seen each other in ten years. But they each came to this party and the three of them danced together. She was barely able to stand, and she came out in this dress that someone had given her, this incredible dress, and just danced and danced. Afterward, she collapsed.

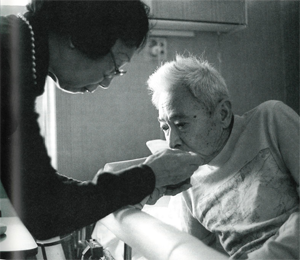

I often synchronized my breath with hers. Especially toward the end, she always wanted to do that. We sat together a lot, as long as she could. She was a meditator, so that was a part of her process, something she wanted to share with other people.

At the time that Nando died, I was there with her mother and her daughter. She had been winding herself up in her bed sheet, drenched in sweat, and it really looked like she was struggling to get out of her body. I leaned over to her and whispered that she was fine, she was fine, and that we were all there with her and there was nothing to be afraid of. She relaxed a bit and her breathing just settled and then it stopped. I remember holding my head next to hers, holding my ear next to her mouth, listening for breath for a long time. And then just accepting that she was gone. I felt incredibly high when she died, a rush came over me, and her mother and daughter experienced the same thing. Just a feeling that she finally released herself.

There was no way I could have done hospice care or cared for Nando without a very firm sitting practice. First, being able to center myself every day through my practice, and to center myself in a place of nonreactive emotion—that was important to my own sanity. And then my practice taught me how to be able to stay present with dying, to stay present in the moment, aware of all the feelings I was experiencing, without just freaking out.

On a deeper level, I honestly think that the only way you can care for a dying person is with a meditative attitude, what Seung Sahn called “don’t-know mind.” It’s very easy to enter into caretaking with all these ideas about what a dying person needs, what you’re ready to give them, and what kind of process they’re going to go through when they die. You protect yourself with these preconceptions. They allow you to avoid confronting death. Even identifying yourself as caregiver does this. And what can happen when you enter the experience in that frame of mind is that you miss the very person who is in front of you.

You need to be able to confront each moment absolutely nakedly, to be open to whatever comes up. Of course, it’s quite rational to want to protect yourself. The reasons are there all the time. During the height of the AIDS epidemic, for instance, when many of the hospice patients were sick with AIDS, it was often necessary to clean up, literally, a lot of shit, a lot of bodily fluids and the like. You’d have your arms in it. And it was very easy to not be present to the dangers of the situation, to take risks when working with a patient. Or to be unreasonable about how dangerous it actually was. So to be clearheaded about the situation required a meditative stance, a stance of uprightness. Seeing what was in front of you, being with it, and watching it change moment to moment. Doing hospice work itself is a form of meditation, and having the sitting practice is like facing death yourself on the cushion. The two things are one.