Once a week, American Buddhist teacher Justin von Bujdoss wakes before sunrise to prepare for a journey north from his home in Brooklyn. After brushing his teeth and changing into his clothes, the former executive director of Chaplaincy and Staff Wellness for New York City’s Department of Correction and ordained repa (or an empowered lay tantric practitioner) of the Karma Kamstang tradition of the Kagyu school of Vajrayana Buddhism steps into his car and begins the hour-long drive to what he calls the “metropolitan city of the dead.”

Roughly seventeen miles northeast of Times Square, past the slowly gentrifying South Bronx neighborhood of Mott Haven and the sprawling Soundview residential complex, as Interstate 278 turns into Highway 95 and the concrete of the city gives way to the oasis of Pelham Bay, is City Island. One of New York’s most remote neighborhoods, City Island is a model of faded New York history and seaside charm. Filled with wood clapboard homes, weathered Victorian mansions, and iconic restaurants, it is a popular summer destination for New Yorkers looking to escape the city heat. Yet just off its shore lies the smaller and lesser-known Hart Island, von Bujdoss’s final destination.

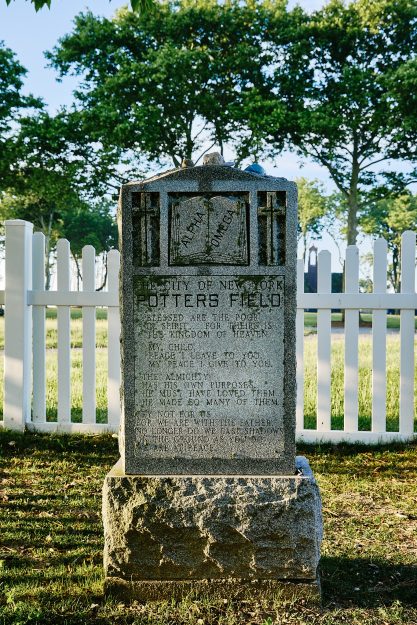

Hart Island holds New York City’s largest tax-funded cemetery. It has been the final resting place for people forgotten and discarded by the city for over a century.

The remains of the deceased stretch back to 1869, when the city purchased the land for use as a potter’s field. Waves of disease outbreaks—yellow fever, smallpox, and cholera—collided with New York’s rapid population explosion of the 19th century, leading to a crisis as its potter’s fields overflowed. Coffins, skulls, and body parts extruded from the ground around landmarks like Trinity Church and the lands where Washington Square and Bryant Park now reside.

Hart Island offered a solution to this problem. Immigrants with no families to claim them, the homeless, unidentified bodies discovered in alleys, flophouses, and rivers, abandoned babies, and even Union soldiers were buried on the island in the ensuing decades. Waves of AIDS victims arrived in the 1980s and ’90s, with COVID victims more recently. Although only a mile long, a third of a mile wide, and totaling 130 acres, the island holds more than a million bodies. It is the largest mass graveyard in the United States.

“Maybe I was made for this place,” says von Bujdoss as he reflects on the journey that led him to the island. He first encountered the power of death as fuel for spiritual practice in India. While studying Buddhism under his teacher Ani Zangmo, he discovered chöd, a tantric ritual practice that roughly translates as “cutting through” afflictive emotions—anger, ignorance, the dualism of self and other, or anything that hinders a practitioner from experiencing a totalizing, nondual awareness, free from fear.

To challenge themselves, yogis who devote themselves to chöd often practice on the edge of charnel grounds, the open-air crematorias that exist across India and the Himalayas. These liminal spaces offer fuel for triggering innate human fears surrounding death, disease, and impermanence. Traveling across India to sites of traditional charnel ground practice—including Sikkim, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bihar—von Bujdoss learned to become comfortable with death.

After spending a decade visiting India to meet with teachers and immerse himself in Buddhist practice, von Bujdoss thought his life path was coming into focus. “I wanted to be a monastic,” he explains, “because that’s what I thought I had to be if I wanted to commit my life to dharma. But my teacher, Ani Zangmo, laughed when I told her that’s what I wanted. She said that would be stupid.”

Zangmo pointed out that there wasn’t a robust support system for monastics in the US. He would also find himself at odds with his culture. Why not commit to maintaining the discipline of a monk internally while outwardly living in the world? Taking her advice, he returned to America. Seeking to merge his Buddhist practices and the need for a career, he began a chaplaincy training program.

His first job brought him to Calvary Hospital in the Bronx as a home hospice chaplain. He spent the next three years tending to individuals and families throughout New York’s five boroughs.

Growing up in the ’80s as a child of SoHo artists, his life in New York revolved around lower Manhattan. However, as a hospice worker, he drove all over the city, meeting clients in all sorts of areas, including the working-class Queens neighborhoods of the Rockaways, Brooklyn’s most neglected public housing complexes, and even a penthouse on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. “The thing I loved about that range is the democratic nature of death,” he says. “Nobody can escape. There’s something so beautiful in that because it joins us all together, not just spiritually but also emotionally.”

His hospice work led him to the city’s Department of Correction, where he first served as a staff chaplain on Rikers Island—New York City’s notoriously violent megajail.

Von Bujdoss spent his first few years serving the prison’s staff. When the department promoted him to executive director of the Chaplaincy and Staff Wellness division, his responsibility grew to oversee the spiritual and physical health of the city’s more than ten thousand corrections officers. It would be this role that would eventually lead him to Hart Island.

At first, he was involved only in assisting with press tours of the island, but this led to being tasked with developing creative responses to highlight the landmark cemetery’s role and history. While the city never actually acted on the plans von Bujdoss developed, the arrival of COVID would soon provide the dharma teacher with a different kind of opportunity.

Von Bujdoss caught COVID in April 2020. While recovering, he received a call from City Hall. Recognizing the scale of the disaster and the need to respect the thousands of New Yorkers being transported to the island for burial, they asked if the repa would be open to blessing the bodies. “Oh my God,” von Bujdoss remembers responding. “Yes.”

Since the early 19th century, Hart Island’s role has been to hide things the city doesn’t want people to see. “City Hall has always wanted to keep this place quiet,” says von Bujdoss. When the city banned boxing in the 1800s, Hart Island was considered “a favorite pugilistic hideaway,” and drew thousands of thrill-seeking spectators. In addition to the cemetery, the island contains a decommissioned Cold War antiaircraft missile system, and it even served as a training ground for New York State’s African American regiments during the Civil War before being turned into a prison camp for Confederate soldiers. Hart Island has also housed a homeless shelter, a boys reform school, a psychiatric institution, and a Civil War memorial. In one field, an open pit lies exposed, displaying the small caskets of the stillborn babies laid to rest on its grounds. Because the city historically protected it from the public and development, the island remains strikingly scenic.

“This is a place of amazing profundity,” says von Bujdoss while waiting for the morgue truck to arrive. “It’s probably one of the most important pilgrimage sites I’ve ever visited.” Talking with von Bujdoss, he says he experiences Hart Island with the same intensity he had once experienced in India’s charnel grounds. “If we want to actualize and complete the path,” he says, “we must realize a place like Hart Island is as important as any temple or pilgrimage site in Asia.”

The sound of gunfire interrupts him—an NYPD firing range is on nearby City Island. Von Bujdoss says they sometimes detonate bombs too. “This place confounds us, because it’s full of contradictions. That’s something humans have a hard time with. Contradictions are uncomfortable. They require us to think and feel for ourselves and not just have an unexamined relationship with things. That’s what makes them rich.”

He explains that learning to find comfort in paradoxes and difficult situations provides a direct path for understanding and embodying the nondual teachings of Vajrayana—like Dzogchen and Mahamudra—that are at the heart of his teaching and personal practice. These practices cultivate the ability to be present and at ease with challenging emotions and situations, allowing practitioners to navigate their circumstances with less resistance and fear.

Von Bujdoss doesn’t see this nonduality as a peak experience exclusive to formal meditation practice. While he recognizes that it may feel that way the first few times, he explains that practices like Dzogchen and Mahamudra familiarize a practitioner with discovering the ordinariness and ubiquity of nonduality in everyday life. “It’s something everyone has experienced in their lives,” he says. “We probably just didn’t recognize it at the time. It’s not an experience owned by any Buddhist lineage, even though they want you to think it is,” he laughs. Von Bujdoss explains that becoming familiar with nonduality helps to increasingly connect us with this world. “We can feel that interconnection,” he says. “It has a felt sense of wisdom that becomes very clear.”

Contradictions are uncomfortable. They require us to think and feel for ourselves and not just have an unexamined relationship with things. That’s what makes them rich.

When the morgue truck finally arrives, it delivers bodies in pine boxes stacked one upon another in the back of a refrigerator truck. As von Bujdoss recites the Lord’s Prayer over the coffins, members of the crew who arrive to bury them greet one another with smiles and high fives.

When he first met the men of the burial crew, they shared with von Bujdoss that they weren’t sure they could handle the job emotionally. But with time, they developed a deep love of the island and their role as gravediggers on it. For von Bujdoss, these very real yet seemingly diametrically opposed images serve as fuel for his practice. The happy burial crew, the sound of gunfire as a ferry carries the morgue truck across the water, and the serene landscape that serves as the final resting place of more than one million individuals all contribute to the presence of life and death as intricately and nakedly entwined, like the image of a Tibetan yab yum thangka.

Standing under the shade of oak trees, the burial crew jokes about the Mets game the night before while von Bujdoss quietly recites prayers. A breeze blows through the branches overhead. Gulls cry in the distance. Deer peer out from the woods near the edge of a field. Manhattan’s skyline is visible on the horizon, engulfed in the stillness of the burial site. Another day was starting in the city, where lives would experience victory and loss, joy and sorrow, life and death.

“This is what buddhanature essentially is,” says von Bujdoss. “It’s connection to something much more vast than how we think of ourselves. Practice is learning how to open up to that experience of vastness. The more we open up to it, the more it becomes increasingly ordinary. Then we can be increasingly comfortable experiencing it in any situation.”

After his blessings, he says goodbye to the burial team and returns to the ferry. A crew member waves him onboard and wishes him a good day. The June air is cool. The sky above is clear, blue, and vast. Von Bujdoss smiles. “Take care,” he replies, “enjoy this weather.”