In late summer of 1972, Robert Aitken was 55 and lived in Hawaii with his wife, Ann, at the Maui Zendo. He had taken a hotel room in Honolulu for the duration of the conferences of the Association for Humanistic Psychology and the Association for Transpersonal Psychology, where he was speaking as a leading Western Zen Buddhist.

It was near the end of the Vietnam War. Robert—or Bob, as he liked to be called—and the other conference attendees, myself included, had been forced out of our original hotel because General Ky and Henry Kissinger were meeting there, and our group was considered a security risk. Some of us from the conference staged a die-in at the hotel, adorning ourselves with red paint and collapsing in the grand foyer.

Bob had studied Zen in Japan and had helped bring such Zen masters as Soen Nakagawa Roshi and Hakuun Yasutani Roshi to America, as well as hosting the Buddhist scholars D. T. Suzuki and Masao Abe. At the time of the conference he was directing two residential Zen training centers in Hawaii: Koko An Zendo in Manoa Valley on Oahu and the Maui Zendo on Maui.

I was 25 and debating how to commit my life energies. I had been accepted into the Buddhist Studies doctoral program at the University of Wisconsin. I was attending these conferences and had arranged to meet with Robert Aitken to decide on a career in academia, psychotherapy, or Zen. I was poised to travel to Japan to enter a Zen monastery.

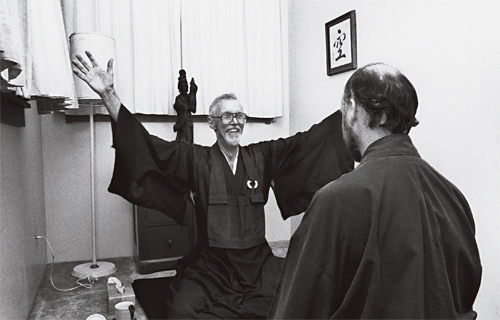

When I arrived at Bob’s hotel room and knocked, he answered the door, an extremely tall and gaunt figure, very serious and sensitive-looking—not exactly severe, but certainly austere. He had black hair combed back and a salt-and-pepper goatee. His way of moving was deliberate and dignified, later reminding me of a line he had translated: “Don’t you see that leisurely man of the Tao…?”

I introduced myself and he nodded, gestured to a chair, and returned to unpacking his clothing and putting it in drawers and the closet. I was used to more conventional civility. This was my initiation into Zen directness—completing an action without distraction.

Five or ten minutes went by without his saying a word. Then he sat down in a chair.

“So you’re thinking of going to Japan to study Zen. What do you think you’ll find there?”

I shared my expectation that I would be embraced by a legion of enlightened Zen adepts, hermits and monastics engaging in long meditations and dharma repartee and eager for me to join them. Bob laughed out loud, one of the few times I can remember him doing so. Then he began disabusing me of my fantasies.

He explained that most of the monastic institutions were training grounds for young men preparing to take over their fathers’ temples. He talked about the vast network of temples running as parishes and funeral businesses where meditation was a rarity, if it occurred at all. He talked about some of the brutality he had experienced at the wrong end of a keisaku [Zen stick] from young monks still smarting from the recent war defeat. He described how nearing the end of a long retreat, a monk lifted his hakama [meditation skirt] and publicly ridiculed him for not sitting in full lotus.

Bob had tremendous respect for the Japanese, Japanese culture, and Zen. In my time with him, I never heard him direct this kind of criticism again. He never complained or talked much about his internment in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, except to recount that men in the camps quickly stopped talking about women and instead fantasized incessantly about food. His words and our further discussion of what Zen practice really entailed changed the course of my life. I don’t think I would have remained in Zen had I gone to Japan in 1972. Instead, I decided to stay in Hawaii and practice with Bob. I stayed there from the summer of 1972 to December of 1973, when I transferred to the Zen Center of Los Angeles.

During my first month in Hawaii, I attended two Zen sesshins [retreats] with Bob. Yasutani Roshi had been coming to lead retreats for Bob periodically and had started many members of the sangha on the koan “Mu.” Bob had been given permission at this time to discuss zazen and practice, and to work with students on this first koan, but not to give koans himself or pass students on koans.

The Harada-Yasutani tradition demanded that practitioners have a strong, clear first awakening and then refine themselves through rigorous training over subsequent decades. Even after the completion of the course of 1,700 koans set by Master Hakuin, only a rare few were empowered as a roshi, a master teacher, and allowed to handle koans with a student.

I wanted to be a really good student, and I tried to make it through my entire first sesshin in full lotus. I had never meditated so long. Despite a seasoned yoga practice, I was nearly in tears with pain by the end of the second night. After lights-out, Bob entered the zendo where I was sleeping with others and massaged my legs. I had no idea he was even aware of my suffering. His compassion was deep, and most often carefully hidden.

The Maui Zendo was remote, surrounded by a guava orchard and a bamboo forest. The residents maintained a thriving vegetable garden. I wanted to live there and have daily contact with Bob, but the Maui Zendo required a full-time commitment. Because of this, students could not hold day jobs. I needed to earn money, so eventually I moved to Bob’s other center, Koko An on Oahu.

About eight Zen students lived at Koko An, working at paying jobs during the day and doing zazen in the mornings and evenings and during weekend retreats. The center was a lovely old house surrounded by avocado and grapefruit trees and gorgeous flowers. Slow rain during zazen was a special treat. A single drop would descend in a series of soft plops hitting palm frond after palm frond. During dawn zazen, a fountain of burbling coos rose with the sun from scores of gray mourning doves davening in the driveway. We meditated in the long, rectangular living room, which comfortably seated about 15 of us. The dining room could be converted for additional seating during retreats.

Bob would come from Maui several times a month to give talks and interviews and lead retreats. His talks were carefully prepared and written out, balancing a scholarly attention to biography, context, and lineage style while also revolving multiple perspectives in a traditional manner. He spoke very precisely with a dry delivery and occasional thrusts of humor accompanied by an engaging small smile. He had a special love of Hakuin’s “Song of Zazen,” often quoting “this very body is Buddha.” To conduct his own koan study, he had to translate the Mumonkan and Hekiganroku with Yamada Roshi, one of Yasutani Roshi’s successors, who had largely created the book The Three Pillars of Zen with Roshi Philip Kapleau. Bob may have done more translations later, but only his Mumonkan was published.

Many of us were fanatic about diets, our own ideas about practice and enlightenment, and our personal concepts of right and wrong. Bob patiently tried to wean us from various absolutes with one of his favorite expressions: “A pure stream has no fish.“ At Koko An Bob had hosted D. T. Suzuki, who in his talk had loosed the shocking statement that “zazen is not necessary for Zen.“ A year later, Bob asked Masao Abe about this, who added, “What Dr. Suzuki meant was that zazen is not absolutely necessary for Zen.”

From time to time Bob offered some spare details from his own life. He made clear that we should not expect Zen practice alone to solve all life’s problems, and shared how psychotherapy had helped him deal better with his own character rigidity and interpersonal conflicts. He was honest and direct. He let us know he had never experienced the dramatic kensho so prized in the Harada-Yasutani tradition; but in Yamada Roshi’s opinion he had come to a gradual awakening.

Bob was very involved at that time in anti–Vietnam War efforts. He had become a pacifist, an antinuclear activist and a tax resister, refusing to pay the percent of his taxes equal to allocations to the Defense Department. He served as an adviser to members of the Fellowship of Reconciliation who had been arrested for pouring blood on records at a military base in Honolulu and were being aggressively prosecuted. I believe that it was during this period of his work with them that he began talking about his wish to see a Buddhist organization similar to the Fellowship of Reconciliation. This wish eventually evolved into the Buddhist Peace Fellowship.

The organization supporting Bob, the Diamond Sangha, was a friendly, relaxed group, led at that time by Duke and Mary Choi. The sangha included Nelson Foster, who became a Dharma Successor; Sensei Paul Shepard, who leads a Zen sangha in Switzerland; Marc Imhoff, who became a prominent scientist directing one of NASA’s largest Earth Observing platforms; and Francis Haar, the photographer. Bob was distrustful of authority, even his own, and never seemed to want to develop a large organization. He provided a very gentle listening ear and a lot of quiet structure and encouragment.

We were expecting Hakuun Yasutani Roshi to come to Hawaii to lead a retreat in 1973 when he suddenly died. The Diamond Sangha was a lay organization and had no priests, so Bob led a service for Yasutani Roshi and shared stories and anecdotes about him. Yasutani had been orphaned young and had grown up in a Zen temple. I remember being left with a picture of him even in old age as very alone, not having attendants, but traveling around Japan on public transportation, running retreats for laypeople and training people for Jukai [precepts ceremony] right up to his death at 88.

After this, Koun Yamada Roshi looked after the Diamond Sangha and directed Bob’s practice. “Music for Zen Meditation” was a very popular album among us reforming hippies, featuring languorous duets between an American clarinetist and a Japanese shakuhachi master. Someone had the temerity to play a bit of the album for Yamada Roshi before a retreat. Yamada Roshi snapped that this music had nothing to do with Zen. Then he went on a bit of a tangent and extolled Beethoven, his works, even his death mask.

We held a reception after the retreat and played a recording of some of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony at Yamada Roshi’s request. Hoping to get a little dharma combat going, I leaned over and quietly asked Bob, “Does Beethoven have more to do with Zen?” Bob responded quietly, “I prefer the playfulness of Mozart.”

My sense that I was totally enlightened was deflated when it took me a year of twice-a-day zazen to count ten breaths in a row once. I did manage to pass Joshu’s “Mu” with Yamada Roshi at the very end of a retreat, too late to do any of the testing questions with him. He empowered Bob to begin working with students on koans after that retreat. When we met to begin the testing questions on “Mu,” Bob looked at me, smiled, and said: “How do you feel about yourself?” It was so intimately stated, so unconventional, and so Zen. There are many different ways to see that question. Essentially, Bob seemed to take real joy in a fellow human being’s relief from some personal suffering. I felt a deep bond with him at that moment, and his caring presence has lasted as a touchstone for my belief that Zen is radically relational and caring.

I had heard about Taizan Maezumi Roshi, who was creating an intense training environment with ordination at the Zen Center of Los Angeles. This seemed to offer a form through which I could dedicate my life to Zen. I visited ZCLA in January 1974 and remained there.

Aitken Roshi was very supportive and stayed in touch throughout the years. I saw him a few other times. He and Yamada Roshi came together once to visit us at ZCLA, and during their stay we went to Nyogen Senzaki’s grave and held a service. Senzaki had been Bob’s first Zen teacher. Another time, Bob came to ZCLA, probably on his way to the opening of Dai Bosatsu Monastery in Livingston Manor, New York. He left us and hitchhiked cross-country to Dai Bosatsu. He came later to stay at ZCLA for a period of study with Maezumi Roshi on the Five Ranks of Master Tozan and on the denbo documents and ritual for dharma transmission. I was Maezumi Roshi’s attendant and went back and forth between them, getting to spend time in intimate discussions with Bob.

After Bob had a stroke a few years ago, I relayed in an email my gratitude to him for deeply shaping my life. Through him I had gained a relational perspective to my understanding of Zen, encouragement in my commitment to social justice, and an appreciation for scholarly rigor to balance spiritual experience.

His secretary wrote me that she had read him my message. She wanted me to know that in response he had commented about me: “No pretense.”

You never know whether a Zen master’s comment is an ironic whack over the head, a hope for your betterment, or an affirmation. Whichever it was, his words stay with me as guidance and a loving farewell for this lifetime.