The mindfulness practices that my teacher, Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh, taught, which have manifested throughout the world in many forms, all begin with awareness of the breath as an anchor to help us come home to ourselves: first, to acknowledge the suffering within us, to generate the capacity to listen to it, and to hold space for it to transform. Thay’s focus as a meditation teacher was to help us look deeply at the suffering in us and around us, knowing that such looking would show us a way out—a way to put love into action.

As his attendant for seventeen years, I observed that the foundation of Thay’s actions was rooted in peace, true love, and right mindfulness. He illuminated the connection between peace within ourselves and peace in the world to allow us to see and understand conflict in a new light, bridging our personal healing and societal healing in the present moment. I learned from Thay that all our actions of body, speech, and mind can cultivate a foundation of internal peace that serves as a sustaining and impactful source of energy for the world around us. “Peace in oneself, peace in the world” is a calligraphy that I have seen my teacher write many times.

Thay was well aware that healing and transformation does not arise in isolation from social change. When there is war, violence, pain, and death in front of us, as there is right now, we may have feelings of anger, sadness, injustice, despair, and even hopelessness. This suffering is not mine or yours alone. It is a collective emotion and experience we all share in the here and now. As mindfulness practitioners, first and foremost, we build the capacity to hold the truth of suffering. In my own practice, I recognize and embrace the violence and anger that has been present in me since childhood. My parents, victims of the American War in Vietnam, confronted profound uncertainties that led to feelings of despair and suffering. My parents fled the country as refugees and did everything in their capacity to ensure that I had a better future than their own. They transmitted all their hopes and aspirations to me and, at the same time, unknowingly transmitted their pain and suffering as well. Their pain and suffering became my own. Suffering and the practice of mindfulness has been a gift. Since I am able to recognize the pain and violence inside of me, I have the capacity to fully recognize and practice with the violence that exists outside of me.

Mindfulness practice is a source of courage that allows us to slow down and to look deeply at the fear and discrimination present inside ourselves. When we can sit with ourselves, recognize, be comfortable with, and love both the most magnificent parts of our being and the more uncomfortable truths that we embody, we give way for profound transformation. This transformation becomes a torch of wisdom in the world—because we have cultivated the capacity to be present for ourselves, for our joy, pain, and suffering, we are able to be present for the joy, pain, and suffering of others and of the world. When we can accept ourselves, we are more able to listen to others and change what may seem to be an impossible situation for the better. In this way, peace is not just a concept, it is an embodied practice that begins with us and how we relate to ourselves and the world around us.

I ask myself: With all the trauma of the current polycrises driven by climate change, with extreme weather events, changing weather patterns, famines, and wars forcing more people to leave their homes in search of a refuge, is peace even possible? Is it naive? Is it really possible to see the truth of what’s needed and to respond with love rather than reacting with fear, separation, self-protection, and blame? Letting go of preconceptions, my response is this: It is possible if we give it a chance. Actions rooted in love and compassion are the only way to solve the crises in the world. It is through deep listening and tending—to our own suffering and the suffering around us—that a path of peace becomes possible.

When we can sit with ourselves, recognize, be comfortable with, and love both the most magnificent parts of our being and the more uncomfortable truths that we embody, we give way for profound transformation.

If we create opportunities for nations, communities, and people with different views to practice deep listening and sharing, there will be change. We will be able to touch the insight of interbeing, which celebrates the beauty of diversity, the beauty of different cultures with all their languages, sciences, music, arts, heritages, and ways of life. If we start to see each other as flowers in the garden of humanity, as Thay liked to say, our ways of seeing start to transform—we start to care for and tend to that garden. We cultivate the seeds of peace and love that lie dormant in our hearts so that our collective garden can flourish. We realize that in the garden of humanity, there is space for all. It liberates us from the view that in order for us to thrive we must destroy the other. Such a view only creates more suffering.

This suffering, of course, is not limited to humans alone—it affects our whole planet. Mother Earth gives us all the conditions necessary for life. She gives and gives, and yet, we keep destroying her. There is an underlying notion that the land is there for us to take and use, but deep ecology unequivocally tells us we are not separate from our environment. The Earth, as I often heard Thay say, is not outside of us: The Earth is us. So when we destroy others to take land, we are destroying the planet, and we are destroying ourselves.

In his writings and through the example of his life, Thay reminded us that we must persist. If we fall into despair, we allow suffering and violence to win. Thay often shared a story from his years of leading the School of Youth for Social Services during the Vietnam War. During this particular instance, he and his young community were helping to rebuild villages that had been destroyed by blanket bombings. There was one particular village that had been bombed and rebuilt again and again and again. The third or fourth time this happened, when Thay mobilized his team of activists to go out and once again rebuild the village, a young student looked at him in despair and asked, “Thay, is this village worth rebuilding if we know that it will be bombed again?” In that moment, Thay shared that he also touched the seed of deep despair. When he recognized this, he took refuge in his mindfulness practice to stay stable. He focused on his breathing to anchor himself as he felt the strong emotions and sensations that were arising within him so that he could create space for an insight into a way forward. Thay teaches us that these feelings are real and natural, and the practice is to embrace them and not to allow them to overwhelm us. It is the mud that leads to the lotus. So, in response to his young student, his answer was simple: Yes, it is worth it. We have to move forward. The rebuilding itself is an expression of love in action. Our actions represent hope that there is still humanity. We will keep showing up again and again, for as long as it takes.

These moments of insight are like stars that shine most brightly when the sky is at its darkest. Do not underestimate the transmission of acts of kindness, love, and care, even if the fruits of our actions are not immediately apparent. Every action counts. Every loving action we offer to our loved ones, our community, our nation, and our world starts with a mindful breath, a smile, a loving thought, a moment of understanding. It starts with the courage to hold space, the courage to listen, the courage to speak, the courage to shine the light of awareness and understanding where there is ignorance, and the courage to love. Rather than focusing on the potential outcomes of our actions, our practice is to be present and to respond to the needs of the present moment. Focusing on what may be is a trap that can lead to despair. We can take care of the future by taking care of the present.

Our actions represent hope that there is still humanity. We will keep showing up again and again, for as long as it takes.

War, conflict, and acts of violence happening all over the world are bells of mindfulness for humanity and each one of us. Reflecting on this and asking myself what I can do, I see that my responsibility is to transform the seeds of discrimination, fear, hatred and violence inside of myself. Only then is it possible for fear to be transformed into connection, violence into peace, and hatred into love. This is our collective responsibility. As Thay wrote [in a 1969 essay “Love in Action,”] “The success of a nonviolent struggle can be measured only in terms of the love and nonviolence attained, not whether a political victory was achieved.”

Even if you only have five minutes, use those five minutes to cultivate peace for yourself and for the world. If you live for ten more years, it is your responsibility to cultivate peace for those ten years, to transmit a path of peace and a culture of peace. However much time you may have, use that time to contribute to the legacy of peace and humanity through our ways of being. This is our practice of transforming wars, including the wars that have not yet broken out, both within us and outside of us. We all have a lot of work to do to give peace a real chance.

Thay’s words are thunderous: Now, wherever you are, don’t take what you have for granted. You are enough. The path of peace begins with the transformation of your own wrong perceptions and views that divide us. It starts with you. Begin now. The time is now.

♦

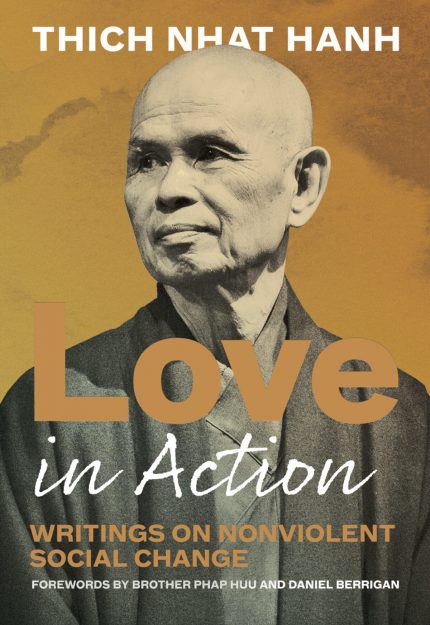

From the foreword to Love in Action: Writings on Nonviolent Social Change (2024) by Thich Nhat Hanh, courtesy of Parallax Press, parallax.org.