“THE LAND OF THE WHITE BARBARIANS is beneath the dignity of a Zen master,” argued Soyen Shaku’s monks when Soyen was invited to the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893. But the Japanese abbot already had high expectations for the new world. Disregarding the objections of his monks, Soyen Shaku (1859-1919) became the first Zen priest to visit the United States. In Chicago, he represented Zen Buddhism with diplomatic discretion. Privately, however, Soyen felt that Zen in Japan had grown impoverished, sapped of true spiritual inquiry. On Soyen’s horizon, the future of Zen rested with the barbarians in the West.

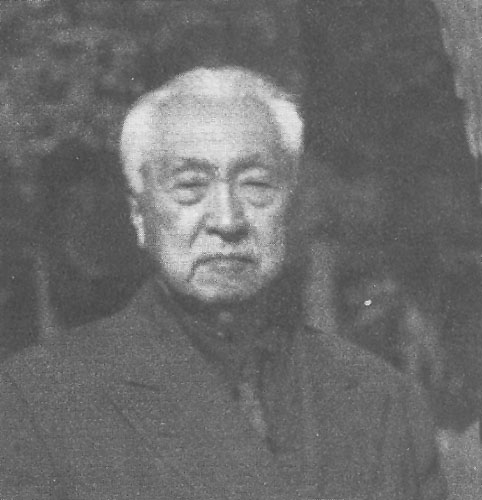

For the first half of the twentieth century, Zen activity in the United States was carried out by Soyen Shaku’s lineage alone, its influence continuing through his two messengers to the West: the world-famous D. T. Suzuki (1869-1966), who became the popularized voice of Zen, and the little-known Zen saint and monk Nyogen Senzaki (1876-1958).

Born in Siberia, the infant Senzaki was found by a Japanese monk at the side of his mother’s frozen body. He came under the care of a Soto priest but was schooled as well in the Shingon faith of his foster father, who also taught him the Chinese classics. Eventually, ill with tuberculosis, he arrived at Engaku Temple to study with Soyen Shaku; during this five-year period of Zen training—sharing, for part of the time, quarters with D. T. Suzuki—he also educated himself in Western philosophy. Then, in a move radically divergent from the conventional training of a Zen monk, Senzaki left the temple to start a nursery school in Hokkaido,Japan’s desolate northern island. Inspired by the German philosopher Friedrich Froebel, he named the school Mentorgarten—a place free of any systematized dogma, where everyone could be both mentor and disciple.

In 1905, Soyen returned to the United States at the invitation of Mr. and Mrs. Alexander Russell of San Francisco, a wealthy and adventurous couple who had met the abbot in Japan. Senzaki joined Soyen, theoretically to raise funds for his school. But Senzaki had been disgusted with the Japanese Zen establishment and its complicity with the Imperial rule. He had compared Buddhist priests to businessmen, their temples to chain stores, and reviled their common pursuit of money, power, and women. Outspoken in his disdain for the titles of the Zen clergy, he criticized the monks, abbots, and bishops for straying from what he believed was the true monk’s path of celibacy and utmost simplicity. He claimed that for genuine Buddhists titles were mere labels, and he abhorred the corrupt practice of selling government-issued Buddhist teaching licenses.

Shortly before arriving in California, Senzaki had also spoken out against the militant nationalism that had fomented the Russo-Japanese War and which the Zen monasteries had supported with as much patriotic fervor as the public sector. Exactly what happened between Senzaki and Soyen no one knows. Robert Aitken Roshi, the American Zen teacher who studied with Senzaki in Los Angeles in the 1950s, suspects that although Soyen would never sever ties with a disciple over political attitudes, he did nonetheless disapprove of Senzaki’s denouncements. It may be that Soyen asked Senzaki to come to the United States. If this is so, whether it was an act of punishment or protection remains one of several mysteries surrounding Senzaki’s relationship with his teacher.

After working as a houseboy for the Russells, Senzaki made his way alone in California with strict instructions from Soyen not to teach for twenty years. Neither of them ever publicly discussed the intent of this twenty-year ban. Most likely Senzaki had not completed his studies, and Aitken suggests that this stiff sentencing to silence was Soyen’s means of instilling, in his own absence, the personal discipline necessary for teaching. As he saw Senzaki off to a Japanese hotel, Soyen told him: “This may be better for you than being my attendant monk. Just face the great city and see whether it conquers you or you conquer it.” This was their last meeting, leaving Senzaki to test his capacity to invent fonn from nothingness. He wrote of his isolation and loneliness, of hours spent in public libraries, and of solitary zazen in public parks. For Senzaki the United States was always, “this strange land.” WIth little command of English and no professional skills, he worked as a dishwasher, houseboy, laundryman, clerk, manager, and, briefly, part owner of a Japanese hotel. He grew his hair out and stopped wearing robes so as not to attract attention, and to reclaim the anonymity he had valued as a monk. In his most poignant effort to adapt to his new country and to be an American gentleman, he studied social dancing.

In 1925, the prescribed twenty years over, he began renting public halls in San Francisco with money saved from his scanty wages. In 1931, Senzaki moved to Los Angeles and opened his Mentorgarten Zendo in the modest rooms of his hotel residence in Little Tokyo. There he and his students did zazen on metal folding chairs that he had purchased secondhand from a funeral parlor; sitting cross-legged on the floor in the customary meditation posture struck him as a most un-American activity.

With Senzaki’s help, Americans began to learn that although Zen training may tame the mind, it does not necessarily lead to mystical awakening; but they also discovered that if the mind can get quiet enough, something sacred will be revealed. Compared to his monastic education under Soyen Shaku, Senzaki gave his students relatively little instruction. Like his dharma brother, D. T. Suzuki, he was careful not to introduce too much too soon. According to Aitken, Senzaki’s students were inspired mostly by his kindness, modesty, patience, and humor. (He once told Aitken, “I like Immanuel Kant. He’s very good, but he just needs one good kick in the pants.”)

But as he shared with his own teacher a sense that Zen in Japan was drifting toward decadence, he encouraged his students to be critical of all beliefs East and West, and tried his best to disabuse them of the tendency toward idol worship and unquestioned acceptance of dogma. His optimism about Zen in this country lay in his understanding that the qualities of self-reliance and pragmatism were essential to both Zen and America. “Zen is based on self-evident fact, and so can convince anyone at any time,” he wrote. “Because it is based on fact, Zen can pass freely through the gates of the innumerable teachings of the world; it offers no resistance and poses no threat, since its foundation is completely non dogmatic. The brighter one polishes his mind-mirror of reason, the more the value of Zen can be appreciated. Because Zen is fact and not ‘religion’ in the conventional sense of the tenn, the American mind, with its scientific cast, takes to it very readily.”

By orthodox standards neither Senzaki nor D.T. Suzuki qualified as a “lineage holder,” since neither received formal “dharma transmission,” the master’s seal of approval to transmit the Zen teachings. Technically, Senzaki and Suzuki represent a break rather than a continuity in Soyen’s lineage. Yet ironically, their lack of pedigree made Senzaki and Suzuki perfect first emissaries to the United States, itself a product of disrupted lineages, and despite Senzaki’s modest following (compared with D.T. Suzuki’s), even his influence has been long-lasting. His isolated and inconspicuous life as a passionate Zen monk in a spiritual wilderness has endeared Senzaki to subsequent generations of American students. A man of no rank, he wanted only to be, as he put it, “a happy Jap in the streets.” And although he had no formal successors, Senzaki transmitted his realization through two pivotal teachers: Nakagawa Soen (1907-1984), who came to the United States through Senzaki, and Haku’un Yasutani (1885-1973) who came through Nakagawa Soen.

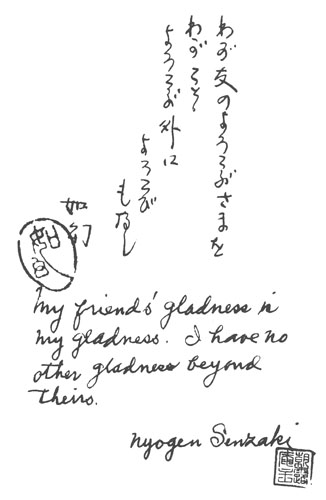

Senzaki collected donations from his students to bring Nakagawa Soen to America. In July 1941 he wrote to the United States consulate general in Tokyo: “Please visa the passport of my Brother monk, Soen Nakagawa.” Five months later, the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Throughout the Second World War, Soen remained in Japan while Senzaki was interned in Wyoming at the Heart Mountain relocation camp for Japanese-Americans. Since Buddhism had spread East from India to China, and east again to Japan, and then to the United States, Senzaki wondered if the wartime roundup ofJapanese-Americans from the Pacific Coast to inland camps was not, in fact, supporting the “eastbound tendency of the teachings.” Making the most of adverse circumstances, he called Heart Mountain “The Mountain of Compassion” and named the zen do he started there “The Meditation Hall of Eastbound Teaching.” Throughout the war, on the twenty-first day of each month, called Dai Bosatsu Day in Japan, Nyogen Senzaki and Nakagawa Soen, with palms together in the traditional gesture of greeting and respect, bowed to each other, dissolving the Pacific Ocean between them.

Senzaki called himself a “kindergarten nurse,” “a “mushroom monk,” a nameless and homeless monk, embodying the very transience he had known from his start in life as an orphan. “You may laugh,” he wrote, “but I am really a mushroom without a very deep root, no branches, no flowers, and probably no seeds.” Indeed, having never received formal dharma transmission, he left no formal dharma heirs. His given name, Nyogen, means “like a phantasm,” and his Buddhist name, “Choro,” means “morning dew.” Both images appear at the end of the Diamond Sutra:

All composite things are like a dream,

A phantasm, a bubble and a shadow;

Like a dewdrop and a flash of lightning—

They are thus to be regarded.

Senzaki had none of the quixotic flash of Jack Kerouac or Alan Watts, who by the time of Senzaki’s death in Los Angeles were generating the “Zen boom” in San Francisco. He offered Zen training, however rudimentary, when there was little interest in it. He was too “square” for Beat Zen, and the Beats had no use for him. “I have neither an aggressive spirit of propaganda,” he said, “nor an attractive personality to draw crowds.” Purity of heart was his special legacy; with time, it has grown more important.

“Mushroom Monk” was adapted from Zen in America, which will be reissued by Kodansha America next year.