Stay too far away from a spiritual teacher, the Tibetans famously warn us, and you cannot feel the heat; draw too close, and you get burned. The fire warnings grow especially urgent when that teacher attracts students through her warmth, and all the more so when the students, in turn, try to put words to the burning they feel around them. That is one reason why lucid and balanced accounts of spiritual communities are so hard to come by: the fires of emotional surrender tend to be so intense on every side-among those who have staked their lives on a community, and on making it work, and among those who’ve turned their backs on it, and defined themselves by that rejection-that the ensuing stories have the unsettling fervor of depositions in a divorce court. “I’ll love him forever.” “He ruined my life.”

Recently, I had reason to think about this again when I came upon the new book by Martha Sherrill, The Buddha from Brooklyn (Random House; 304 pages; $25), one of the most measured and disciplined accountings of a circle of idealists I can remember reading. Sherrill first came to Catherine Burroughs and the Tibetan Buddhist center she founded in Poolesville, Maryland as a reporter for the Washington Post Style section, intrigued by the sound of a big-haired, Simpsons-watching former psychic from Brooklyn who had suddenly been recognized as the incarnation of a seventeenth-century Tibetan saint. She warmed instantly to Jetsunma Akhon Norbu Lhamo-as Burroughs was now known-grew close to many of the one hundred or so students who had gathered around her, and even began to dream of her vivid and consuming presence, and to consider buying property near Kunzang Palyul Choling (or “KPC,” as the students call it); yet even as she was clearly rooting for the center to succeed, her journalist’s instincts prompted her to watch, and to record in minute detail, all the scandals (of money and sex, of course) that threatened to undo the community, as they have done so many others, and to devote much of her narrative to following a young nun who ended up fleeing the place and having Jetsunma arrested for battery.

The Buddha from Brooklyn struck me as an unusually clear and close look at all the hazards-and potential-of trying to set up a spiritual community in America, as seen by an outsider pledged to objectivity and eager to learn; but more than that, and more valuably, it charts a heartrending and all but universal story about the costs of idealism and the mixed blessings of devotion, and about what happens when our sweetest ideals get entangled in reality and Realpolitik and the very complications we had hoped to leave behind. Much more than Jetsunma, it tells us about the price of faith.

Every teacher of spiritual values is a koan of sorts, part mirror, part Ozymandian riddle, but in this case the koan came with all the oversized intensity of a Technicolor marquee in Las Vegas. Jetsunma, a Dutch-Italian-Jewish daughter of a sometime grocery-store clerk and a convicted thief, made a practice-perhaps a point-of not conforming to anyone’s ideas of enlightenment (and does so to this day with her followers in Sedona, Arizona). Quoting unabashedly from Comedy Central, going to the manicurist once a week, and sporting a vanity plate that said, “OM AH HUM,” she especially unsettled her students’ easy assumptions (and ours) by parading a new young lover, of either sex, with every passing season. Most of what made and makes her sympathetic, in fact, is that she comes across as such a typically confused woman of her generation-worrying about her weight, eager to reverse a losing streak of four lost husbands, and more than ready to talk about her makeup, her problems with men, and her “abusive childhood.” What Sherrill sees in her, among other things, is vulnerability. And when she listens to her speak, dispensing sensible, practical tips about compassion, seasoned with talk of “the first big aha” and “Hell-ooo,” the visitor can’t help but be impressed by her emphasis on social action and the heart. On the big screen she would be played by Bette Midler.

Yet this full-throated and seemingly down-to-earth, even ambitious woman-dreaming of making her fortune through hair-care devices with “built-in gel paks that could be heated in a microwave” and once the subject of psychiatric study-was seen by Penor Rinpoche, head of the Nyingma lineage (the oldest school in Tibetan Buddhism), questioned for a while, and then pronounced to be the reincarnation of a Tibetan saint. The rinpoche (so revered in India, Sherrill tells us, that followers collect the pieces of soil he’s walked on) was clearly impressed by her ability to attract students, and apparently undeterred by the fact that his new acolyte, until recently, had been a channeler of the prophet Jeremiah and of “Andor, who claimed to be the head of the Intergalactic Council.”

Stranger things have happened, of course, and the incarnation system is all about finding a divine light in unexpected, undiscovered places. Yet this constantly unexpected saga challenges our assumptions in all kinds of fresh and unusual ways. We’re used, after all, to taking wisdom from eccentric Zen masters and from charismatic Tibetans who breach every conventional notion of propriety and sobriety, telling us that everything they do-eating pizza, watching TV, having sex-is, if seen in the right light, a form of service and instruction. Why should we not extend the same trust to an American woman who’s been recognized by one of them? Why are we more comfortable with a teacher who looks exotic or otherworldly than with someone who looks, in Sherrill’s words, like a “Beverly Hills real estate agent” and doesn’t hide her failings? Isn’t the very definition of American opportunity that, to amend the old adage, every girl can grow up to be a Buddha?

Jetsunma’s story, to me, dramatized many of the questions that shadow every spiritual center, precisely because it played itself out in such extravagant and colorful terms; and the stakes involved intensified because the “Fully Awakened Dharma Continent of Absolute Clear Light” (as Sherrill translates KPC’s official title) quickly-very quickly-became the largest collection of Tibetan monks and (mostly) nuns in America. Jetsunma’s students, in short, were not just practicing meditation, or listening to Tibetan teachers; they were actually donning robes, adopting new names, and reciting vows in a language they couldn’t understand. Yet these solemn oaths-that, for example, they were not hermaphrodites, and were not animals or spirits, and that they would not drink, have sex, or dance for pleasure-were all being taken by a group of typical Americans: Redskin fans, former Jesuits, a six-foot female personal trainer from Bally, and a man who had sold weapons parts to Third World countries. Their story is essentially the classic (and unanswerable) one of what happens when good and imperfect souls aspire to perfection.

None of this is particular to Buddhism, of course-Christian groups are often much the same. But the difficulties of pursuing their ideal were surely compounded by the fact that these students were committing themselves to a discipline so far, in time and space, from everything they knew. Every single aspect of Tibetan Buddhism-the relation between the sexes, the nature of hierarchy, the very meaning of obedience-had little relation to what they had grown up with and nothing to do with the notions of punishment and sacrifice that they imported from their all-American homes. Even the self they were so eagerly trying to dissolve might be said to have a different quality, a different meaning, in many parts of Asia where people tend to define themselves in terms of a family, a company, or even a country. To take another example, the essence of Zen, as I understand it, is “nothing special”; yet how can it possibly be nothing special to someone who has leaped across a great cultural divide, taken on a whole universe of alien customs and words, and abandoned everything he knows to embrace it?

This makes for a kind of double standard that globalism intensifies: Billy Graham, for example, tells us to think of others, and most of the people I know will write him off (if only because he comes encrusted in so many of the associations and affiliations they’ve spent their whole lives trying to escape); the Dalai Lama says the same thing and they write it down as gospel. This is, you could say, an argument for the virtue of observing “foreign” traditions-that they enable us to hear what we are deaf to in our own-but it does make for curiosities. Many of us in the West might feel a little strange if a group of Tibetans suddenly donned Benedictine monks’ robes, renamed themselves “Aelred” or “Isaiah” and recited prayers to the Virgin Mary in a language they couldn’t follow. It’s happened for centuries, of course-India is full of Johns and Thomases-but the fact remains that a Mormon in a village in China, or a Catholic in Hanoi, is facing all kinds of challenges that his counterparts in Utah or in Rome don’t have to think about.

This all becomes relevant here because Jetsunma, not untypically, began to demand that her followers treat her as Tibetans might treat their guru. In Tibet-Jetsunma’s students learn-it’s not unheard of for disciples to be beaten with logs and clubs, and in certain circles just to step on the shadow of a teacher is to consign yourself to one of the eighteen hells; yet in an America where even rapping a fifth-grader on the knuckles is frowned upon, and where the governing myths are those of democracy, it all gets more entangled. Jetsunma, to take a trifling example, would throw snowballs at her students, but they were not allowed to throw them back at her. Was this a training in humility, or just an exploitation of their trustfulness? The students-perhaps Jetsunma herself-did not have the background or context to know for sure.

The paradox at the heart of all spiritual communities-poignantly acute in a tradition that stresses going it alone-is that the commitment to the impersonal generally takes shape around a personality; and generally it is a personality so strong and powerful that what began as a community begins to look like a cult. In Poolesville, as so often, the hardworking, deeply devoted students were not, it seems, reminded of the Dalai Lama’s frequent injunction: “Students should make sure that they don’t spoil the guru.” They started collecting Jetsunma’s discarded acrylic fingernails as students sometimes do in India, tufts of her cut hair, and even a discarded toilet seat from her house; one of the disciples flew to Chicago, at her own expense, to rescue a mail-order coat that had got stranded in a warehouse. “Ideally, if you saw a dakini walk down the road and cut the head off a sweet infant child,” one especially loyal student says, “your only thought should be, Oh what a lucky child.”

None of this, of course, reflects on Buddhism as it is known in most places, and none of it, either, says that the students were wrong to act on what moved them. But it did set up a situation that Buddhists of every stripe, and members of any idealistic circle, can surely recognize. When things start looking strange, some students may do everything they can to give the teacher the benefit of the doubt, and use the new terms they’ve picked up to justify the community (or, more, to justify their commitment to it); some may just jump to another group, in the philosophical equivalent of the “rebound.” Some may hang on because they know that their alternatives in the “real world” are all a kind of defeat, and some may turn away because ideals never look so good when they’re put into earthly practice. But all of them, at some level, face the same agonizing question: What do you do when your heart is shaking so hard you feel it’s going to shatter?

The Tibetans who came to inspect the goings-on in Poolesville were not slow to give Jetsunma herself a training in humility; besides, they were shocked when they found, for example, that she used an electric zapper to kill insects around the property. At the same time, not surprisingly, they were stunned by the energy and devotion of the students, who committed themselves without complaint to twelve-hour prayer vigils. And the questions for all parties only intensified when Jetsunma, in the style familiar from male teachers, started elevating her young lovers, one after another, to consort status, only to drop them again just as quickly, leaving everyone to wonder whether what they had witnessed was an affair of convenience or of the heart. How much was the teacher just gratifying herself, and how much was she really trying to woo people to the dharma?

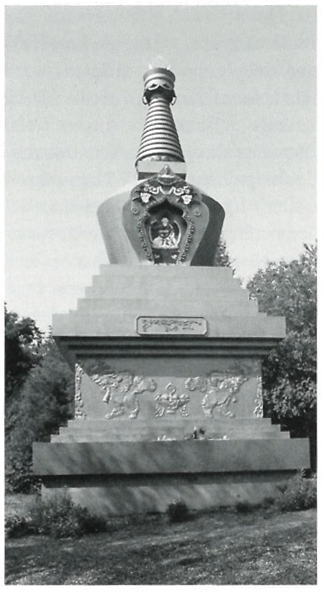

In Sherrill’s rendering, all this came into focus around the stupas Jetsunma wanted her students to build. A stupa, she felt, was the best way to spread a beneficent current of healing and goodness around the world at large. Yet in the process of constructing one, funds were depleted, students were badly injured, and plans kept getting so out of hand that Jetsunma might have been charged with what, in the Philippines of Imelda and Ferdinand Marcos, was called an “edifice complex.”

By the time The Buddha from Brooklyn approaches its climax, fully fifty percent of the center’s operating expenses are going to Jetsunma’s salary and students who are slow to pay their rent are condemned as “anti-Buddhists.” In the book’s most horrifying section, when Jetsunma learns that a monk and a quiet nun are growing intimate, she humiliates them publicly, slaps the young nun (who has been in a hospital, earlier that same evening, after being involved in a car crash), and virtually pulverizes them with a terrifying poem of hellfire that combines spiritual blackmail with near-obscenity. Previously, when the same nun had had her virginity stolen by a Tibetan monk in India, Jetsunma had virtually denied the incident (and on another occasion, too, when she had had a falling out with one of her own husbands, she had got her students to stab effigies of him). Though Jetsunma’s explanations of everything continue to be sensible and even humble, by book’s end she and Sherrill have almost switched places: It is the journalist who is practicing a form of Buddhist prayer, while the teacher talks marketing and media (excited as she is by a proposed movie about her life, and contemplating a $4,500-per-month P.R. person to push the hair-care products). If power corrupts, spiritual power corrupts at the source, the soul.

It would be easy-too easy-at this point just to dismiss the whole project, or to write it off as an aberration. Sherrill, thankfully, refuses such simplifications. She has witnessed much too much cruelty and heartbreak to say, blithely, “Better to have cared and lost than never to have cared at all”; and yet she cannot deny, as she frequently tells us, that the world of devotion is “a generous place. An unselfish and forgiving and unconditional place.” And Jetsunma had shown an admirable confidence and trust in opening herself so fully to a journalist (perhaps because she was so sure she could win her over). The “spiritual world,” says Sherrill, “was in many ways as brutal as the newsroom I came from” (and I, having spent time around both newsrooms and spiritual communities, would agree); yet she also recognizes that, in the context of the bustle and striving she knows in her usual environment, the peace and pointedness of Poolesville have a particular glow. Above all, she cannot deny the possibility that the people she met in the community were in many cases leading lives of much greater selflessness and purpose and depth than they had led before or might in other circumstances.

Those who are deeply immersed in Buddhism in America may well respond to the challenge of this book by reducing it all to politics and personalities: Penor Rinpoche, after all, who all but endorsed this unorthodox project, is the same lama who named Steven Seagal as a terton, or “treasure-revealer,” in 1997, surprising the world. And those close to Jetsunma, as well as those once close to her, will doubtless find much to quarrel with in Sherrill’s account, because it is even-handed. But for me it is precisely because her life was not on the line in Poolesville that Sherrill could rise above sectarian differences and raise questions that anyone should consider: how much is the students’ reluctance to question Jetsunma a reluctance to question themselves? How much is their devotion the result not of hopefulness but fear-or loneliness or need? When Jetsunma, towards the end, seems chastened and quiet-talking of her fears and feelings of worthlessness (and of the fact that her students won’t let her acknowledge them)-how much is she, in a sense, as much a prisoner and victim of the situation they’ve set up as her students are? For once, the journalist, not fully inside the conflagration-yet not entirely out of it-has a useful vantage point.

Sherrill underlines the sense of the book as parable by going off, before drawing conclusions, to talk to Tammy Faye Bakker and Laura Schlessinger, and to consider the parallel stories of groups in every tradition, not least the Mormons, who, out of beginnings no less eccentric, have built “the richest and most successful church” in America. Anyone who joins a community of hope, from Brook Farm to Castro’s Cuba, is committing herself, essentially, to living with contradiction, and to forsaking easy answers for ever deepening questions. And if conviction is what separates us, as Peter Ustinov has said, doubt, at some level, is what brings us together. The Dalai Lama, faced with the proliferation of incarnations of Tibetan tulkus around the world, told me that he found many of them “a little incredible”; yet, much more importantly, he said, as he always does, that if a teacher is of benefit to even one human being, who are we to write her off? Sherrill concludes her story, courageously, by conceding that she felt “kind of humbled and encouraged and uplifted” by all the kindness and devotion she’d seen around the stupa, even though much of it had led to disappointment and hurt; her life has clearly been changed by the experience, and not for the worse. An outsider, looking at such a place, might talk about the dangers of “brainwashing”; an insider would say that if her brain has been made clean, that’s surely all to the good.