Phantom Moon

Phantom Moon

Duncan Sheik

Atlantic/Nonesuch, 2001

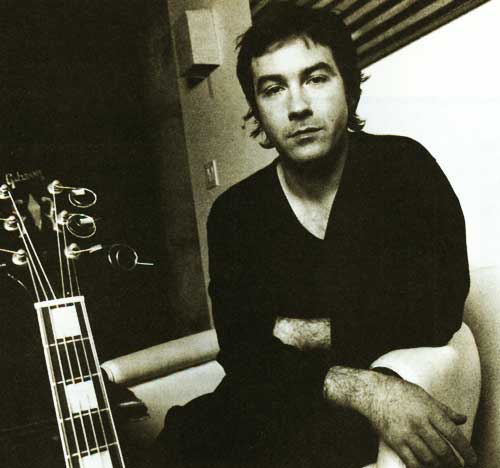

In 1996, when Duncan Sheik released his first album, he made success look easy. But soon there was a backlash, and when his second album failed to sell as quickly as the first, skeptics were quick to pronounce him a one-hit wonder. Some of his strengths wotked against him: The very fact that radio stations had embraced his first single, “Barely Breathing,” with such runaway enthusiasm undercut the idea that he might be considered a serious songwriter. Then there was the matter of his movie-star good looks. When you’re working in Bob Dylan’s territory, handsomeness can erode credibility faster than an endorsement for Kmarr.

But Sheik’s third and most recent album should help erase any doubts about his place in the musical pantheon. If there were a fork in the road dividing Elvis Presley (above all, a sex symbol and pop icon) and Elvis Costello (a songwriter first and foremost), with the release of Phantom Moon Sheik strides confidently in Costello’s footsteps. While it is no put-down to note that Sheik’s sense of melodic possibility is still dwarfed by Costello’s (the same could be said of nearly anyone who wasn’t a Beatle, and one or two who were), Sheik is following the great British runesmith in three ways.

Most directly, he’s tapped the talents of Kevin Killen, the same engineer Costello used for his first “serious” musical side project, the Brodsky Quarter. Second, while Costello most recently polished his high-culture credibility by pairing with mezzosoprano Sophie von Orrer, Phantom Moon finds Sheik collaborating with playwright Steven Sater, a lyricist who helps lend the songs more than a whiff of literary erudition. And third, Phantom Moon has something markedly Anglophilic about it: the chamber arrangements courtesy of the London Sessions Orchestra and references to Trafalgar Square and Shakespeare are only the most overt examples.

Ultimately, it is another Briton, the late Nick Drake, who provides the most direct inspiration for this elegiac cycle of paeans to romantic yearning. Sheik has been known to perform Drake’sPink Moon album live in its entirety, and the title of Phantom Moon is a none-too-subtle reference to his hero. The album opens with a few slow piano chords, a wisp of a song over which Sheik half sings, half speaks the words. In keeping with Drake’s devotion to subtlety and ennui, Phantom Moon finds Sheik turning the volume ever lower, barely breathing each word into the microphone. The effect isn’t sullen but deeply somber. Too much care and orchestration has been put into these ghostly, literary portraits of the exquisite ache of love for it to come off as mournful. But make no mistake, despite moments of real prettiness, Phantom Moon is concerned with only one of the Four Noble Truths: the first. Whether suffering has a cause, a solution, or any way of being dealt with never comes up. Instead, the narrator of these songs seems to have accepted that he will remain lost, frozen, in a dream of beckoning mermaids who “spread their arms and lift pale portrait faces,” as Sheik intones in “Sad Stephen’s Song.”

Although Sheik is a member of Soka Gakkai International (he met Sater, who directs the Buddhist organization’s arts division, through the sangha), this is an album almost entirely free of explicit references to spiritual practices (which is probably a good thing—few outside of Van Morrison have pulled that off in a pop setting). Only one song, “A Mirror in the Heart,” shifts away from the album’s obsession with existential and romantic loneliness to suggest that the solution to all of the heartache described with such preciousness on Phantom Moon might lie within.

Still, there is one sense in which a Buddhist lesson can be derived from listening to Phantom Moon: Whether by being delicately chimerical or deliberately uncertain, the music defies grasping, and in that way provides listeners with a good opportunity to practice listening without any solid idea to hold on to. ▼