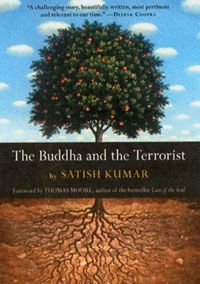

THE BUDDHA AND THE TERRORIST

SATISH KUMAR

Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2006

144 pp.; $12.95 (cloth)

The story of the Buddha’s encounter with Angulimala, a criminal so vicious he wore a necklace of human fingers, will be familiar to many Buddhists. It is a popular parable and has been adapted and retold many times; it is incorporated into Thich Nhat Hanh’s Old Path White Clouds as well as Osama Tezuka’s epic Buddha comic. And while even those completely unfamiliar with the tale may guess the ending (if Angulimala had proven incorrigible, all those Buddha statues today would be missing a few fingers), it remains a powerful statement of the power of nonviolence and compassion.

Satish Kumar leads readers once more through this memorable ground with his eloquent and highly accessible work The Buddha and the Terrorist. Born in India, Kumar ordained as a Jain monk at the age of nine, then left the order at eighteen and became a renowned peace and environmental activist. He began an eight-thousand- mile peace pilgrimage on foot in 1962 to promote nuclear disarmament, and later settled in England, where he became a co-founder, and now is Pro- gram Director of Schumacher College in Devon, England. An author and editor as well as an educator, Kumar won the Jamnalal Bajaj International Award in 2001 for promoting the values of Mahatma Gandhi outside India.

In this newest book, Kumar uses Angulimala’s transformation as a vehicle to convey many basic Buddhist teachings. The Buddha defies the warning he is given and seeks out Angulimala in the forest. “It might be the job of the King to kill the criminals,” he explains to one villager, “but the calling of the Buddha is to transform them, awaken them, and liberate them from ignorance.” Even after he has won over the criminal and taken him “across the river of sorrow and suffering,” he must convince the King that Angulimala should be allowed to live in peace with the sangha, that “forgiveness is superior to justice.” Even then, the great master and the King together must still dissuade Angulimala’s many victims from seek- ing vengeance, remind- ing them that “we cannot bring your beloved ones back to life by killing Angulimala.” Eventually, Angulimala himself becomes a teacher of the dharma.

By referring to Angulimala as a “terrorist,” Kumar politicizes the story. The original Buddhist scripture does not really support this title, as there are no indications there that Anguli- mala has any political intentions. In a more direct translation of the Pali sutra by Thanissaro Bhikku (available online

at www.accesstoinsight.org), he is called simply a “bandit,” a term used likewise by many other translators, while Thich Nhat Hanh calls him a “murderer.” Kumar acknowledges this discrepancy from the Buddhist canon in the introduction, explaining that “in the version which I learned from my mother in my early childhood, Angulimala is born an outcaste, an untouchable,” and that he “suffers from degradation and discrimination, which turns him into a rebel.” In this reading, Angulimala is a deluded freedom-fighter of sorts who

kills in order to “take control of society” and “bring an end to the oppression and segregation.”

This is an interesting and provocative interpretation, and leads Kumar to emphasize the social context of Angulimala’s crimes: he suggests that “fear is violence, caste discrimination is violence, exploitation of others, however subtle, is violence,” and that “we need to look at the root causes of violence.” But highlighting the motivation behind the gruesome violence muddles the underlying message. When Angulimala ultimately becomes a monk, he not only renounces violence but also seems to drop his political aspirations. If we believe that his goals were just, despite his decidedly unenlightened methods, then it is not clear that this resolution is a happy one. After all, in Kumar’s account the moral seems to not be that nonviolence is a better way to liberate the oppressed—the position of outcastes in Indian society is unchanged at the end of the story, and caste discrimination still exists twenty-five hundred years later—but rather that nonviolence is the “more effective way to overcome terror” committed by the would-be liberators.

To be fair, this is not the reading Kumar intends. A longtime believer in Gandhian principles, he has argued elsewhere that nonviolence is a path to freedom for the oppressed. But that lesson is hard to derive from this story. In the end, Angulimala’s story is one of personal redemption, not of Buddhist values in the service of broad social change.

Still, few would question Kumar’s assertion that “in our troubled times we need to be courageous, creative, and compassionate, and to use our imagination in order to build a better future.” This challenging little book pushes us toward such a reexamination, even if in the end it does not provide any ready answers. It takes a brave writer to suggest that terrorists should be loved rather than fought, that even the most hardened criminal can become an enlightened teacher. Yet if we believe that change is possible in this life, why shouldn’t it be possible for a man like Angulimala? And if change is not possible, what hope is there for any of us?