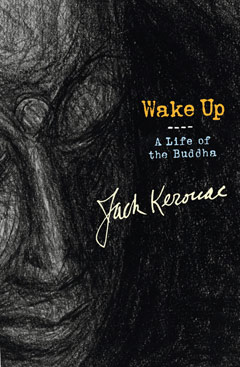

Wake Up: A Life Of The Buddha

By Jack Kerouac

New York: Viking Adult, 2008

160 pp., $24.95 (cloth)

There is no definitive life of the Buddha. All biographers, all creative expressions of the Buddha’s life rely on story fragments—some old, some older—and anyone who takes up the challenge must construct his own tale. I think the Buddha would have welcomed this process, since, by his own declaration, his life was a worthy and fruitful subject of investigation and contemplation.

There is no definitive life of the Buddha. All biographers, all creative expressions of the Buddha’s life rely on story fragments—some old, some older—and anyone who takes up the challenge must construct his own tale. I think the Buddha would have welcomed this process, since, by his own declaration, his life was a worthy and fruitful subject of investigation and contemplation.

In Jack Kerouac’s tribute, Wake Up: A Life of the Buddha, the great Beat poet and novelist has left a puzzling and provocative work. Although written in 1955 and serialized in Tricycle starting with the Summer 1993 issue, it has not been published in book form until now. Wake Up is a spicy mix, hard to digest, but an intriguing read that may be just right for some.

In the interest of full disclosure, I come to Kerouac’s work having embarked on a similar endeavor. I wrote, and have been performing, a one-man play about the life of the Buddha that relies exclusively on the sutras. The project came from a desire to understand the man’s life and original teachings and, to the extent possible, distinguish traditional Buddhist teachings from pop-cultural embellishment that, it seemed to me, had often strayed significantly from the Buddha’s original message. To prepare the play, I immersed myself in the sutras for several years and for background read numerous other accounts of his life. Biographies of the Buddha inevitably reflect the agenda and cultural milieu of their authors. Kerouac’s is no exception.

Kerouac’s Catholicism infuses the story from the start. As an epigraph, he opens with a prayer, “Adoration to Jesus Christ, / … Adoration to Gotama Sakyamuni,” written by Dwight Goddard, a former Christian minister who compiled The Buddhist Bible, the book that triggered Kerouac’s interest in Buddhism and was one of his main sources for Wake Up. Like the gospel writers of his native Christianity Kerouac states his purpose unequivocally: “I have designed this to be a handbook for Western understanding of the ancient Law. The purpose is to convert.”

The book begins as if in conversation, with Kerouac telling us a bit about the person and a bit about his philosophy. “This young man who couldn’t be tempted by a harem-full of beautiful girls because of the wisdom of his great sorrow, was Gotama, born Siddhartha in 563 B.C.” The main events in the early life of the Buddha are left suitably intact, with Kerouac recounting the Buddha’s marriage, the birth of his son, his disillusionment and subsequent departure from home. In Siddhartha’s great quest, his practice of the meditative absorptions is intermingled with ascetic practices, and soon thereafter we witness the Buddha’s enlightenment. Kerouac takes great liberty at this point, adorning the episode with his unique language, and it is in these unfortunately all-too-infrequent episodes that Kerouac’s voice resounds and the work really soars:

It had been a long time already finished, the ancient dream of life, the tears of the many-mothered sadness, the myriads of fathers in the dust, eternities of lost afternoons of sisters and brothers, the sleepy cock crow, the insect cave, the pitiful instinct all wasted on emptiness, the great huge drowsy Golden Age sensation that opened in his brain that this knowledge was older than the world.

Kerouac then returns to his casual tone, relating the rest of the Buddha’s life through familiar sequences: delivering his first sermon to his five companions from his days as an ascetic; encountering the rich merchant’s son, Yasa, whose backstory parallels the Buddha’s; converting the large community of fire-worshipers; and finally, engaging in a rather drawn-out (and un-referenced) metaphysical dialogue with Ananda, the Buddha’s attendant and one of his key disciples. This part is told in the dry and informational style of the sutras. But then, in recounting the Buddha’s death, Kerouac offers a final highlight with peculiar and evocative imagery: “The moon paled, the river sobbed, a mental breeze bowed down the trees.”

There you have it—Kerouac-cum- Buddha.

At its best, Kerouac’s contribution is in the intermittent poetry of his rendition. The narrative, however, lacks the singular force of Herman Hesse’s stunning Siddhartha, which, through radical reorganization of the episodes, adds dimension and power to the already profound story of the Buddha’s life. Kerouac’s work may be satisfying for Kerouac-lovers, but it’s not very illuminating for those seeking further insight into the Buddha. All this seems odd in light of Kerouac’s stated purpose “to convert,” since it is his wonderful strangeness and impulsive tonal innovation that draw the reader’s attention away from the subject matter. Conversion implies convincing, and it’s hard to be convinced when we’re so distracted by the voice of the teacher. But perhaps that’s what Kerouac intended. Perhaps he hoped his uneven style would invite further investigation.

Another source of frustration is the book’s lack of reference and scholarship. Kerouac states, “This book follows what the sutras say. It contains quotations from the Sacred Scriptures of the Buddhist Canon, some quoted directly, some mingled with new words, some not quotations but made up of new words of my own selection.” In the end, the absence of citation contributes to the confusion surrounding an already commonly misunderstood philosophy. Were the work squarely fiction, like Siddhartha, I could simply read and enjoy. But if I’m to take this as an instructional text, as the author suggests, I want to know the sources, or at least be able to distinguish those “new words of my own selection” from “quotations from the Sacred Scriptures of the Buddhist Canon.” It is just this kind of unreferenced discourse, in which the teacher’s ideas meld inconspicuously with the Buddha’s original doctrine, that contributes to the misunderstanding of Buddhism as vague, self-contradictory, nihilistic, or some kind of anything-goes philosophy.

One highlight of Wake Up is Robert Thurman’s extensive and illuminating introduction, which fills in the historical context, contributing substantially to the read. He also supplies much detail about Kerouac’s approach to Buddhism and the characters populating his life when he wrote the book. It was interesting to learn the opinion of Kerouac’s friend Alan Watts, who “was heard to say that he might have had ‘some Zen flesh but no Zen bones’”—a reference to a book by a well-known Zen author, Paul Reps. Thurman also discusses at length Kerouac’s strong Catholic faith—which is such an important element in the book— noting that in his semifictional work Dharma Bums, Kerouac called the Buddha “the Jesus of Asia.”

Perhaps Wake Up is most interesting in the context of Kerouac’s stormy life and the radical Beat movement that he named. Like Kerouac, the Buddha must have been a passionate man. He renounced home and everything dear to him to seek an end to suffering. And when it came down to it, he laid his life on the line as he vowed to sit at the root of the Bodhi Tree until he awakened. In the Jataka Nidana we read: “Let only my bones remain, but not until I attain the supreme enlightenment will I give up this seat!” The man was ready to die. To die. And Kerouac lived such a life. He stands, to this day, as a hero of nonconformity and innovation. The author and his subject were not dissimilar in other ways—both charismatic, exceedingly handsome, and leaders of mass movements established during their lifetimes. Above all, they were fierce and fearless creative innovators.