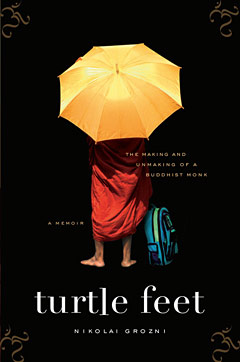

Turtle Feet: The Making And Unmaking Of A Buddist Monk

By Nikolai Grozni

New York: Riverhead Books, 2008

336 pp., $24.95 (cloth)

The role of monasticism in Buddhist life is a great challenge in the West. To many converts here, the 227 rules for Therevada monks (and 331 rules for nuns) seem rigid and inflexible, exactly the sort of stuffiness they had rejected when embracing Buddhism. To others, shaved heads and funny robes can seem cultish or just plain weird.

The role of monasticism in Buddhist life is a great challenge in the West. To many converts here, the 227 rules for Therevada monks (and 331 rules for nuns) seem rigid and inflexible, exactly the sort of stuffiness they had rejected when embracing Buddhism. To others, shaved heads and funny robes can seem cultish or just plain weird.

In Turtle Feet, the young Bulgarian-born musician and writer Nikolai Grozni recounts his own two-and-ahalf years in funny robes as a Tibetan Buddhist monk in India, “without newspapers, radio, TV, jazz, non- Tibetan books, social obligations, a girlfriend, and a nine-to-five job.” The result is a thoroughly entertaining exploration of Buddhist monasticism from the inside—and a unique view into the Tibetan refugee community and Buddhism itself.

Grozni’s prose is both evocative and unsentimental, as in this early description of arriving in Dharamsala, the capital city of the Tibetan diaspora, shortly after his ordination:

Since it was July, the Himalayas looked like a collapsing mud cake: roads gave way to uprooted crags, fortifications yielded to sinking houses, electricity poles pointed to the horizon, water pipes burst and dug gullies. … Dharamsala’s main street was right below us—a narrow dirt road lined with rows of shops and restaurants stacked upon one another like towers made from a mishmash of incompatible construction sets. A web of telephone wires, dilapidated awnings, and dirty plastic sheets wrapped the street and all buildings, giving the impression of a village seized by a monster spider.

Grozni is 22 when he arrives in India, a recent dropout from the Berklee College of Music in Boston. He immerses himself in Tibetan language and culture, and studies Buddhist doctrine with unusual intensity. Judging by his writing here, these efforts bore fruit, and his explanations of the dharma are penetrating and clear. He devotes much time to emptiness, which he defines elegantly as “the idea that exteriors don’t represent the inner essence of objects, … that every experience is superficial, a mere gloss.” He even manages his own one-sentence reworking of the Four Noble Truths:

Reality was a construct; because it was a construct, it never worked the way you expected it to; perpetuating this construct was the same as perpetuating sorrow; dissolving this construct was the end of sorrow.

One lesson of Buddhism is that unlike fiction, life does not have a plot. Characters float in and out, events do not follow easy narratives, and many hours are wasted on trivial pursuits that do not make for interesting reading. The challenge for a memoirist like Grozni is to pretend otherwise without resorting to wholesale fabrication. For the most part, he succeeds. The overarching story is pegged to Grozni’s friend, Tsar, a Bosnian and fellow monk stranded in India as his home country disintegrates into war. Grozni’s friendship with Tsar also provides an opportunity for him to comment on their shared bond of Balkan culture: a love of chess and cigarettes, and an indigenous fatalism he describes as “the sense that you come into this world deprived and destined to end up in the gutter, and that whatever good happens to you is always the result of chance or some wild statistical aberration.”

THE CAST of secondary characters in Turtle Feet is entertaining and well drawn; it includes Damien, “a 22–year-old guy from L.A. who talked about Eastern philosophy the way rappers talk about the ’hood” (as in “I dig the dharma, bro”), and Hans, a German monk who says things like “votch carefully” and “I am zeh master.” The Tibetans we meet are similarly engaging, if somewhat more enigmatic. The motherly Ani Dawa, “a tiny Tibetan nun in her forties,” is a nearly constant presence for much of the book, guiding Grozni through his studies. His later teacher, Geshe Yama Tseten, is wonderfully grumpy, predicting that Grozni will renounce his vows, “go back to the West, lead a meaningless life, and die a fool.” (He got the first part right, at least.)

Buddhist schools in the West have dealt with monasticism in various ways. Much of the American Soto Zen community has embraced a very open style of ordained clergy, with equality of men and women and no long-term celibacy. Tibetan Buddhists here are often more ambivalent, honoring visiting monks and nuns but not encouraging the monastic path for local sangha members. Others, including many Vipassana sanghas, have dispensed with formal ordination altogether, focusing on lay practice exclusively.

In the end, Grozni, too, rejects monasticism, at least as a lifelong path. “I didn’t want to parade my spirituality through the streets,” he explains. Still, he finds renouncing his vows harder than taking them had been. “I missed my robes,” he admits. “It is so easy for us to find something to hide behind.”

At the close of this splendid spiritual memoir, Grozni leaves the “amplified silence” of the Himalayas, returning to the West to “fall in love” and “write silly books.” But his time in robes was not wasted. “In order to understand something clearly,” he tells us, “one must first give it up.”